In Depth

To begin we’ll address the on-going confusion between the validity of the names Paraceratherium, Indricotherium and Baluchitherium. These are all separate genera’s established as homes for fossil material belonging to huge terrestrial mammals that are very similar to one another in form. In fact they are so similar that many palaeontologists consider them to be the same animal, and Baluchitherium at least is now universally regarded as a synonym to Paraceratherium. More confusion comes from the names Paraceratherium and Indricotherium as both have appeared frequently in popular media such as books, television shows, and websites, as well as Indricotherium actually being the type genus to the group which Paraceratherium is classed under.

However later study, principally by S. G. Lucas and J. C. Sobus in 1989, has been finding that Paraceratherium and Indricotherium are actually one and the same animal. The important thing to realise here is that Paraceratherium was named first in 1911, while Indricotherium was named in 1915. Unless a case along the lines of an older name not being recognised for such a long time (as happened with the dinosaur Tyrannosaurus) can be established the oldest name must always have priority over any subsequent namings. However given the frequent exposure that Paraceratherium has received since its discovery and naming, this today would be impossible. To this end those who recognise Indricotherium to be the same animal as Paraceratherium, treat it as a synonym to the latter thus labelling the material as Paraceratherium transouralicum (from the original Indricotherium transouralicum). Controversial renaming is nothing new in palaeontology and perhaps the best analogy to use here is that of the dinosaur Apatosaurus, which today is still sometimes referred to as Brontosaurus by those who don’t know their history.

Naming controversy is not the only problem that Paraceratherium has had to overcome since its discovery. Initially only the skull of Paraceratherium was known to science and in form it led many of the palaeontologists of the day to draw similarities between it and the skull of a rhino. Although the fossils were not yet known, the rest of the animal was assumed to be rhino like upon this observation. The earliest reconstructions were of a large rhino like creature, no horn as there was no attachment point for one, a large heavily built body with a tough hide supported by four squat legs. However further discoveries gradually allowed for a more accurate construction to be pieced together, with the most critical discovery being that of the legs which revealed a more gracile, but more importantly a longer, taller build. Today Paraceratherium is reconstructed as a giraffe like animal, but with a substantially more robust build than that of the giraffes we know today. Despite this analysis Paraceratherium is still more popularly regarded as being related to rhinos.

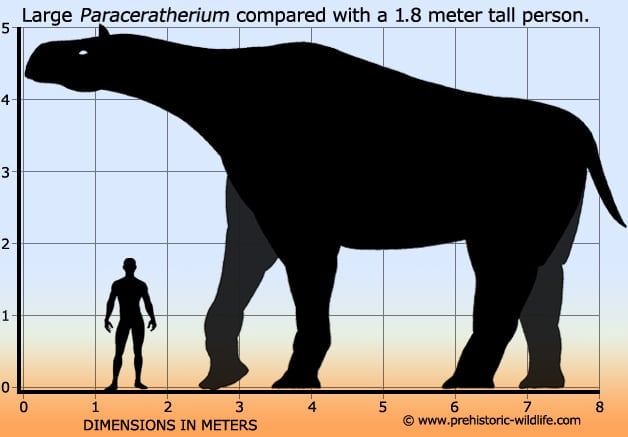

Paraceratherium remains today as the largest terrestrial (land) mammal ever known to exist. This has been confirmed by the discovery of the largest species, Paraceratherium orgosensis from China. The large size of Paraceratherium meant that it would have been quite comfortable living the life of a high browser, feeding from the tree canopy. Again this is another similarity to a giraffe, this time in terms of an ecological niche as by browsing tall growing vegetation, Paraceratherium could exist and not compete with the multitude of smaller herbivorous animals that could not reach so high. The long legs of Paraceratherium supported the weight of the body from underneath like columns and because of their longer length allowing for a bigger stride, would have allowed for more energy efficient locomotion over longer distances.

It is popularly thought that Paraceratherium had muscular lips that allowed it to grip and manipulate food before placing it in its mouth. This is supported by the shape of the forward portions of the skull which is similar to other animals that have such an adaptation. Paraceratherium also had two pairs on enlarged incisor teeth, the pair in the upper jaw pointing downwards while the lower pair projected slightly forwards. This may have been an adaptation for holding branches steady in the mouth while the lips manipulated the digestible parts from them.

Further Reading

– Paraceratherium bugtiense, a new genus of Rhinocerotidae from the Bugti Hills of Baluchistan. Preliminary notice. – Ann. Mag. Nat. Hist. 8 (8): 711–716. – Clive Forster Cooper – 1911. – The largest land mammal ever imagined. – Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society (107): 85–101. – Mikael Fortelius & Jonh Keppelman – 1993. – New remains of the baluchithere Paraceratherium bugtiense (Pilgrim, 1910) from the Late/latest Oligocene of the Bugti hills, Balochistan, Pakistan – Journal of Asian Earth Sciences 24: 71–77. – Pierre-Olivier Antoine, Dario de Franceschi, S.M. Ibrahim Shah, Laurent Marivaux, Iqbal U. Cheema, Gre�goire Me�tais, Jean-Yves Crochet & Jean-Loup Welcomme – 2004. – Building Baluchitherium and Indricotherium: Imperial and International Networks in Early-Twentieth Century Paleontology. – Journal of the History of Biology (Submitted manuscript). 48 (2): 237–78. – C. Manias – 2014.