In Depth

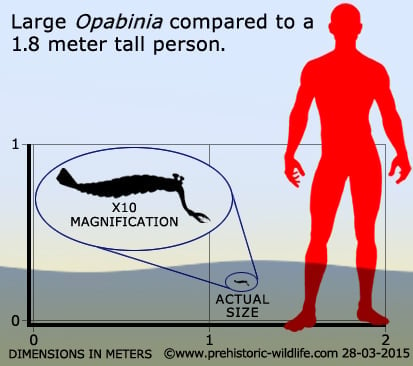

Perhaps the best word to describe Opabinia is bizarre. With five eyes, a forward facing proboscis a third of the length of the body and a mouth that is not only on the underside of the body but faces backwards, and you end up with a creature like no other we know of today. However when you look at Opabinia within the context of other Burgess Shale creatures such as Hallucigenia, Wiwaxia and Anomalocaris, then Opabinia actually begins to look quite normal.

Opabinia is loosely defined as a lobopod in that its body was arranged in segments called ‘lobes’. However while superficially similar to later creatures like trilobites, the lobes of Opabinia seem to have been soft, without the hard exoskeleton that later arthropods would possess. This soft body has often been distorted during the preservation process resulting in slightly different reconstructions depending upon the specimen being described. Also because the body was soft, the internal organs of Opabinia are sometimes revealed in impressions. This means it takes an experienced eye to identify these organs and not to mistake them for external features. The lobes that came out from the sides of the main body were flat and projected at a downwards angle. These lobes also overlapped one another with the rear edge resting over the top of the front edge of the lobe behind it. Markings on these lobes are interpreted as being gills, and are present on all but the first lobes either side. However these gills have been interpreted to being on both either the top or lower sides of the lobes. If the gills were underneath they would have been protected from above. However if the gills were on the top of lobe they would have been protected from below as well as having a greater exposure to the flow of sea water due to the overlapping arrangement of the lobes.

The lobes of Opabinia also made a ‘V’ shaped tail formed by two sets of three lobes that rose up either side from the rear of the tail. This gave Opabinia a tail loosely reminiscent of modern day fighter jet, and may have served a stabilising purpose.

It’s possible that Opabinia could swim above the bottom by rippling its outer lobes in sequence so that it maintained the same level it needed to be. While this form of movement would not have been fast, or indeed powerful against a strong current, it would have allowed for stable positioning over areas where Opabinia had found suitable food sources.

The proboscis of Opabinia terminated in a pincer which had spines that pointed forwards and inwards on the inner sides of the claws. What this pincer was used on is difficult to say as it would have equally been able to grasp small soft bodied organisms as well as small chunks of organic matter. The low number of Opabinia specimens in relation to other species may point towards the latter carnivore theory. Assuming this low occurrence is not a result of the true numbers not being preserved, Carnivorous animals are usually less common than other kinds of animals so that they do not exhaust their food supply.

The rest of the proboscis itself was roughly a third of the length of the body and is striated in multiple cross sections. This suggests that the proboscis was flexible, and when combined with the length, it is theoretically possible for the proboscis to pick up a food item and curl round underneath to deposit the food into the mouth. This would also explain why the mouth faces backwards instead of just facing down, as the proboscis could curve along its natural curvature when delivering food for processing. The length and flexibility of the proboscis also meant that Opabinia could search between cracks and crevices for food where smaller items could be hidden. Because the mouth on Opabinia faced backwards its gut had a strong ‘U’ shaped bend which food would have to pass around. Once inside the food would make its way down the length of the body as it passed down the gut.

As stated above, Opabinia had five eyes, something that is very unusual as animals today tend to have even numbers of eyes. These eyes are arranges into two rows on the head with two on the front row, three on the back row behind them. These eyes where situated on short stalks that pointed upwards at slight angles. The middle eye of the back row of three had a stalk that was shorter than the rest suggesting that it just pointed directly upwards. How these eyes worked is not entirely known. Some have suggested that they were compound eyes, although there is no fossil evidence to suggest this. However all five eyes working together may have actually had a result similar to the basic concept of a single compound eye. Given the position of Opabinia in the fossil record its eyes would have been probably been very basic with no way near the ability to produce images like we see them today. They would however probably have been able to distinguish between shapes of light and dark, essentially a simple photoreceptor. By having five photoreceptors positioned together and pointing in slightly different directions to one another (the same concept as individual lenses of a compound eye), Opabinia would be able to ‘see’ dark shapes passing over head as the object passed over the receptors preventing surface light from reaching them. These ‘objects’ may have been the forms of potential predators that Opabinia could interpret as being the sign to take cover to avoid being seen. Further support for this theory comes from the fact that the eyes predominantly point at upwards angles rather than just forward.

Perhaps the most confusing feature about Opabinia, or at least the part that produces the strongest debate amongst researchers are the small triangular structures that are on the underside of the main body. These were initially interpreted in 1975 by H. B. Whittington as being extensions of the gut, with an alternative suggestion in 1994 by Chen et al. being that they were part of side lobes.

However in 1996 G. E. Budd stated that these triangular forms could not have been internal structures, and that they were also separate from the lobes being lower down the body. This resulted in the first speculation that these conical structures were actually legs, something that seemed to be confirmed when he found mineralised patches that seemed to correspond to hard claws on the ends of the legs.

Although this seems plausible a new study undertaken in 2007 by X. Zhang and B. E. G. Briggs stated that the conical ‘legs’ actually had the same chemical composition as the gut, seemingly confirming the original interpretation by Whittington. They also suggested that the lobes and gills of Opabinia were biramous as seen in crustaceans, and that Opabinia may be representative of the form that originated this design. However a subsequent 2011 paper by G. E. Budd and A. C. Daley suggested that the chemical composition similarity is not exclusive to the gut, but is in fact indicative of the mineralisation that occurs in fluid filled cavities like you would find in other lobopod legs.

If Opabinia had working legs then it would not have needed to always swim to get about, although this in itself would not suggest that Opabinia was incapable of swimming by moving the side lobes in a wave like fashion. The presence of legs if confirmed beyond dispute would probably lead to a change in traditional reconstructions of Opabinia slowly swimming just above the bottom.

Because Opabinia does not feature any defining characteristics its exact position among other creatures is still uncertain, although most people agree that it is similar to members of both the Onychophoria and the Tardigrades. Also while Opabinia is more advanced than more basal lobopods, it is not as advanced as the later arthropods which had hard exoskeletons. Further fossil evidence may yet clarify this matter, but until then the phylogenetic position of Opabinia will continue to be decided by debate.

Further Reading

– The enigmatic animal Opabinia regalis, Middle Cambrian Burgess Shale, British Columbia. – Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 271 (910): 1–43 271. – H. B. Whittington – 1975. – Opabinia and Anomalocaris, unique Cambrian arthropods. – Lethaia 19 (3): 241–246. – J. Bergstr�m – 1986. – The morphology of Opabinia regalis and the reconstruction of the arthropod stem-group. – Lethaia 29 (1): 1–14. – G. E. Budd – 1996. – The nature and significance of the appendages of Opabinia from the Middle Cambrian Burgess Shale. – Lethaia 40 (2): 161–173. – X. Zhang & D. E. G. Briggs – 2007. – The lobes and lobopods of Opabinia regalis from the middle Cambrian Burgess Shale. – Lethaia 45: 83. – G. E. Budd & A. C. Daley – 2011.