In Depth

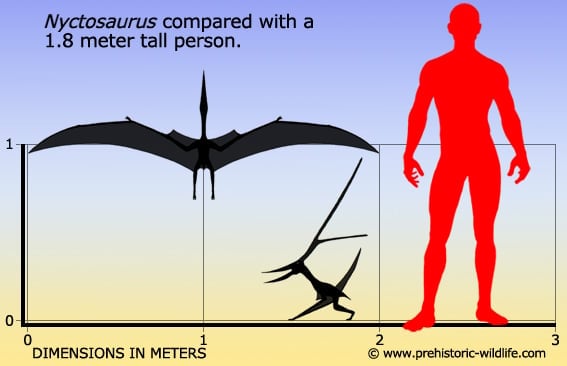

Although many pterosaurs sported elaborate head crests, Nyctosaurus took things to a new extreme. Rising up to over half a meter high, a proportionately massive ‘L’ shaped crest is known to have been present on Nyctosaurus. This crest was once thought to have been the support for a skin sail, but today it is generally accepted that the crest was more or less as it was preserved, with it sometimes being referred to as a pterosaur ‘deer antler’ from its appearance. Although it may appear cumbersome, the crest was actually very light, and studies have shown it would have had very little impact upon the flying ability of Nyctosaurus. It is however somewhat harder to say if it actually imparted any positive benefits.

Study of sub adult specimens has raised the notion that Nyctosaurus reached full size within its first year, and that the crest started growing when the individual in question reached adulthood. The crest may have been growing throughout the entire adult life of Nyctosaurus, with the largest crests belonging to the oldest, and henceforth most successful individuals. This would serve to persuade potential mates that the larger crest was superior to the smaller.

Another special feature of Nyctosaurus is the complete absence of claws from the first, second and third digits of the hand. This means that Nyctosaurus would have had a hard time clinging onto things while on the ground and has brought the suggestion that Nyctosaurus may have spent most of its time flying in the air. A potential benefit of the lack of claws however is that the wings would have been even more streamlined. Because the fossils of Nyctosaurus are known from the Niobrara Formation, it’s a safe assumption that it would have flown over the Western Interior Seaway while looking for fish. With the exception of the head crest being completely different, Nyctosaurus often draws comparisons with the well-known pterosaur, Pteranodon. Not only do they have similar body morphology, both Nyctosaurus and Pteranodon have been found in the same fossil formation, and both would have shared the skies of the late Cretaceous at the same time as one another. However Nyctosaurus has a much shorter presence in the fossil record of approximately only half a million years, whereas Pteranodon spanned over seven million years.

Because of its similar body morphology to Pteranodon, Nyctosaurus may have flown in a similar manner, including using a process known as dynamic soaring. Dynamic soaring is where a flying creature such as an Albatross flies into the trough formed by two waves and into the lee of a passing wave. The lee is the change that results in stronger air pressure that occurs as the wave moves along, and this pressure results in air moving faster over the wings and increasing their lift. The animal in question can then turn around sharply, a process called ‘wheeling’, and then head back towards the trough with a back wind that further increases speed.

The number of species attributed to Nyctosaurus has changed since its discovery, and even some of the species listed above may yet prove to be identical to the type species. Only time with further study and hopefully new fossils will be able to establish the exact species with certainty.

Further Reading

– Notice of a new sub-order of Pterosauria. – American Journal of Science, 11(3): 507-509. – O. C. Marsh – 1876a. – Principal characters of American pterodactyls. – American Journal of Science, 12: 479-480. – O. C. Marsh – 1876b. – Note on American pterodactyls. – American Journal of Science, 21: 342-343. – O. C. Marsh – 1881. – New crested specimens of the Late Cretaceous pterosaur Nyctosaurus. – Pal�ontologische Zeitschrift, 77: 61-75. – S. C. Bennett – 2003. – Posture, Locomotion, and Paleoecology of Pterosaurs. – Geological Society of America – S. Chatterjee & R. J. Templin – 2004. – Aerodynamic characteristics of the crest with membrane attachment on Cretaceous pterodactyloid Nyctosaurus. – Acta Geologica Sinica, 83(1): 25-32. – L. Xing, J. Wu, Y. Lu & Q. Ji – 2009.