In Depth

The Introduction of Megalosaurus to Science

Megalosaurus was the dinosaur that started a great many things including the science of palaeontology, the debate about if dinosaurs should be called names that end with ‘saurus’ because they are not ‘lizards’, to lifetimes of fascination about the creatures that once walked the Earth when we ourselves were an evolutionary dream.

What is thought to be the first fragment of Megalosaurus was discovered way back in 1676, and was recovered from a limestone quarry in Oxfordshire. Although only drawings of this bone exist today it was described at the time as part of a femur by Robert Plot, a chemistry professor at Oxford University. However due to the unprecedented nature of the find, he declared it to belong to a giant human, citing the mention of giants in the bible as a reference. In 1763 the bone was given the name ‘Scrotum humanum’ by Richard Brookes, due to the rather crass yet accurate appearance of the end of the bone to a human scrotum. However this name was never formerly accepted by any scientific body, and has always been interpreted as a description of the drawing of the bone, and was never put forward to represent the binomial name. Today the ICZN, the body that governs the naming of animals, has not made any special effort to protect the name Megalosaurus as they insist it is the correct and valid name for the genus, and that Brookes’s name is not valid.

The man most often associated with Megalosaurus is the Rev. William Buckland who had acquired further fossil material from the same location as the ‘first’ bone in 1815. Buckland continued to puzzle over what animal these bones belonged to until Georges Cuvier, the first man to correctly identify Pterodactylus as a flying reptile, declared the bones to belong to some kind of giant lizard-like creature. Compiling and describing as many fossils as he could, Buckland wrote a paper titled ‘Notice on the Megalosaurus or great Fossil Lizard of Stonesfield’. You have to remember that the title dinosaur would not be created until 1842 by Richard Owen.Megalosaurus - The Dinosaur

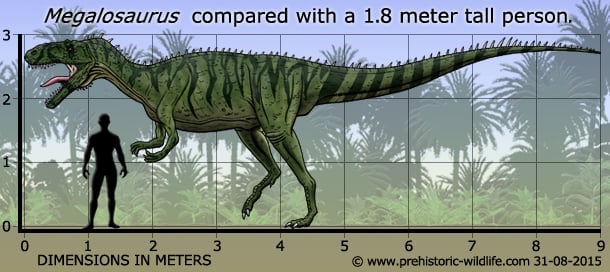

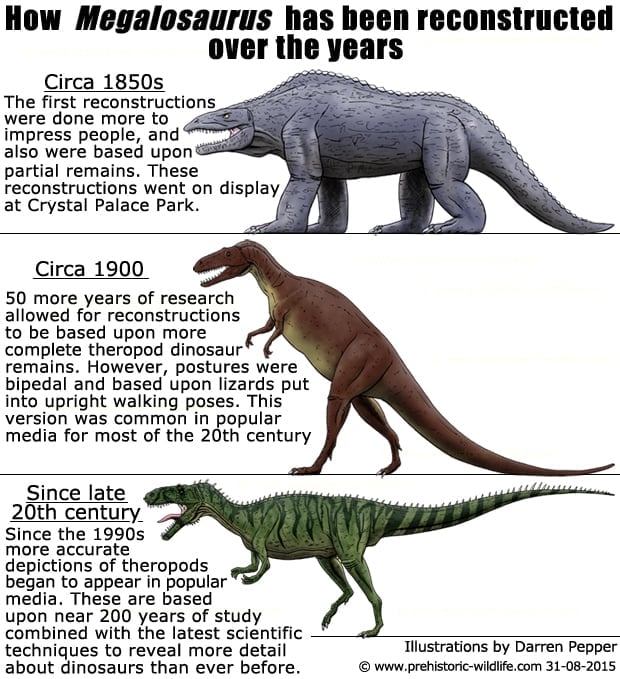

Early reconstructions depicted Megalosaurus more as a quadrupedal reptilian bear rather that the bipedal theropods that everyone is familiar with today. As far as the people reconstructing it were concerned ‘Megalosaurus was a big lizard, so we’ll build a big lizard’. The out-dated reconstruction of Megalosaurus can be seen at Crystal Palace, London, and although grossly inaccurate it has become a landmark in itself. A famous drawing by �douard Riou from the era also shows two giant quadrupedal lizards identified as Megalosaurus and Iguanodon (the second dinosaur ever discovered) tearing chunks of flesh out of each other in some primordial battle. Needless to say this is also inaccurate as not only were they not reconstructed correctly, Iguanodon was a herbivore and would not think to bite a chunk out of a Megalosaurus.

Eventually further theropod discoveries from different parts of the world towards the end of the nineteenth century resulted in what were more accurate reconstructions, although by modern standards they were still inaccurate. Megalosaurus was now depicted as a large bipedal theropod, one of and possibly the largest one active in Europe during the Jurassic.

Because Megalosaurus remains are so often associated with marine deposits the suggestion can be made that Megalosaurus frequent coastal regions at least some of the time, and from this a number of lifestyles can be inferred. One is that Megalosaurus was just like any other carnivorous theropod, hunting inland and only being on the cost coincidentally. The second is that Megalosaurus may have been taking advantage of special types of prey such as small plesiosaurs that were resting on the land. The third is that Megalosaurus was a beach comber, scavenging washed up bodies or visiting tidal pools for trapped fish. The fourth and probably most likely is all of the above.

Megalosaurus was a large theropod and would have needed to make use of every available source, especially when you consider that the higher ocean levels of the Jurassic turned Europe into a chain of Islands that significantly reduced the available land mass for supporting terrestrial animals. Also Megalosaurus probably did not stick to one kind of prey of food source throughout its entire life, and probably changed its behaviour and strategy during different stages of its life.Megalosaurus - The Wastebasket

Megalosaurus quickly captured the attention of the public and even pop culture when it got a brief reference in the Charles Dickens’ classic Bleak House. However Megalosaurus ended up being a victim of its own fame and success, with subsequent theropod discoveries being assigned to it upon the basis of, ‘its an unidentified theropod, we’ll chuck it in with Megalosaurus’. The same thing happened to other extinct animals such as Pterodactylus, and was a practice born out of a lack of understanding. Back in the early days of palaeontology there was no internet, books on the subjects of extinct animals were very basic, and only a small number of people had access to scientific papers that detailed new discoveries, and these were often months or even years old when they became available to people on the other side of the world.

This is why the vast majority of fossils once attributed to Megalosaurus have since been reclassified into different genera and species, some including very familiar names such as Dilophosaurus and Carcharodontosaurus. The advent of new diagnostics techniques, air travel, increased understanding of biology, and the internet which allows scientific papers to be downloaded within seconds of their publication has allowed many of the previous mistakes to be corrected, although the process of making sure that everything is correct as well as processing new discoveries continues to this day.

Further Reading

– Notice on the Megalosaurus or great Fossil Lizard of Stonesfield – Transactions of the Geological Society of London. 2 1 (2): 390–396. – W. Buckland – 1824. – Illustrations of the geology of Sussex: a general view of the geological relations of the southeastern part of England, with figures and descriptions of the fossils of Tilgate Forest. – London: Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons. p. 92. – G. Mantell – 1827. – Report on British fossil reptiles, part II – Report of the British Association for the Advancement of Science 11: 32–37. – Richard Owen – 1842. – List of extinct Vertebrata, the remains of which have been discovered in the region of the Missouri river, with remarks on their geological age – Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 9: 89–91. – J. Liedy – 1857. – On the upper jaw of Megalosaurus – Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society 25: 311–314. – T. Huxley – 1869. – On the reptile fauna of the Gosau Formation preserved in the Geological Museum of the University of Vienna – Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London 37: 620–707. – H. G. Seeley – 1881. – On the dinosaurs from the Maastricht beds – Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London 39 (1–4): 246–253. – H. G. Seeley – 1883. – On a skull of Megalosaurus from the Great Oolite of Minchinhampton (Gloucestershire) – Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London 66 (262): 111–115. – A. S. Woodward – 1910. – Carnivorous Saurischia in Europe since the Triassic – Bulletin of the Geological Society of America 34: 449–458. – F. von Huene – 1923. – On several known and unknown reptiles of the order Saurischia from England and France – Annals and Magazine of Natural History. 9 17 (101): 473–489 – F. von Huene – 1926. – Scrotum humanum Brookes 1763 – the first named dinosaur – Journal of Insignificant Research 5: 14–15. – L. B. Halstead – 1970. – Megalosaurids from the Bajocian (Middle Jurassic) of Dorset – Palaeontology 17 (2): 325–339. – M. Waldman – 1974. – Scrotum humanum Brookes – the earliest name for a dinosaur – Modern Geology 18. pp. 221–224. – L. B. Halstead & W. A. S. Sarjeant – 1993. – Material Referred to Megalosaurus (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Middle Jurassic of Stonesfield, Oxfordshire, England: one taxon or two – Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association 115 (4): 359–366.- J. J. Day & P. M. Barrett – 2004. – Megalosaurus chubutensis del Corro: un posible Carcharodontosauridae del Chubut – Ameghiniana. issue 41 – F. Poblete & J. O. Calvo – 2004. – The taxonomic status of Megalosaurus bucklandii (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from the Middle Jurassic of Oxfordshire, UK – Palaeontology 51 (2): 419–424. – R. B. J. Benson, P. M. Barrett, H. P. Powell & D. B. Norman – 2008. – A redescription of ‘Megalosaurus’ hesperis (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from the Inferior Oolite (Bajocian, Middle Jurassic) of Dorset, United Kingdom – Zootaxa 1931: 57–67. – R. B. J. Benson – 2008. – An assessment of variability in theropod dinosaur remains from the Bathonian (Middle Jurassic) of Stonesfield and New Park Quarry, UK and taxonomic implications for Megalosaurus bucklandii and Iliosuchus incognitus – Palaeontology 52 (4): 857–877. – R. B. J. Benson – 2009. – A description of Megalosaurus bucklandii (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Bathonian of the UK and the relationships of Middle Jurassic theropods – Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 158 (4): 882. – R. B. J. Benson – 2010.