In Depth

Although often associated with Western Europe where remains were first documented, Megaloceros was actually widespread across Eurasia.

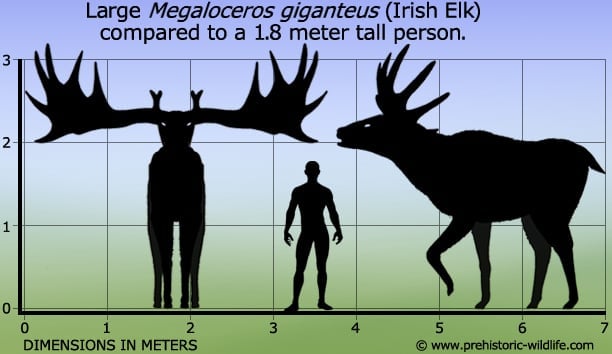

The type species of Megaloceros, M. giganteus, is by far the largest and is more commonly known as the ‘Irish Elk’, ‘Irish Deer’ or just simply ‘Giant Deer’.

As a genus however, Megaloceros shows a varied number of sizes across its many species, some of which strongly support the idea of insular dwarfism.

This is where isolated populations on small bodies of land grow smaller with successive populations so that they do not eat up all of the plants and end up starving into extinction.

Aside from Megaloceros another Pleistocene mammal that displays strong insular dwarfism is the pygmy mammoth Mammuthus exilis.

The full size range of Megaloceros is hard to establish with certainty as different palaeontologists have differing interpretations of the validity of species.

Many of the synonyms and species noted above, though widely accepted, are sometimes still listed as being valid or in positions where they are sub groups to the genus.

These interpretations come about from the overall similarity of giant deer remains that have been recovered from across Eurasia that although different, still closely match one another in form and proportion.

Today the smallest species of Megaloceros is credited as being M. cazioti that was less than one meter tall at the shoulder.

However another Pleistocene deer from the island of Crete called Candiacervus rhopalophorus grew to sixty-five centimetres high at the shoulder and is thought by many to actually be a sub genus to Megaloceros.

Regardless of size however, studies have shown that the antlers of Megaloceros, while different in form between species, would always be in roughly the same proportion to the body no matter how big the animal.

Cave art from early humans depicts Megaloceros as having a dark coat of fur with a white underside, quite similar to other deer today.

The art also shows Megaloceros to have had a small hump above its shoulders which has been interpreted as being for the storage of body fat for survival in lean times.

The presence of a hump is supported by observation of the forward dorsal vertebrae on Megaloceros which have enlarged neural spines (bony projections that point up from the vertebrae) that would have granted structured support for a hump.

This hump adaptation was not unique to Megaloceros however, as other large Eurasian mammals such as the woolly rhino Coelodonta, and even woolly mammoths also have enlarged neural spines for supporting humps.

The large antlers of Megaloceros were once the basis of a controversial theory regarding its extinction where the antlers are considered to have grown so heavy that male Megaloceros could not even lift their heads when they had full antlers.

Needless to say that this is considered highly unlikely because animals that handicapped themselves in such a way would not be able to continue the species for several hundred thousand years.

However the original theory might not actually be too far off the mark with the antlers actually being the root weakness that prevented Megaloceros from adapting to new conditions.

Deer antlers are not permanent structures and after the breeding season the males always shed them so that they are left with two bloody stumps on the top of their head.

After this a set of new antlers is grown, but they have to grow fast and large in time for the next breeding season.

This requires a good supply of nutrients from plants, but the bodies of male deer will also use up nutrients that are stored in the bones to make up any shortfall in nutrients from the regular diet.

This is where climate change at the end of the Pleistocene becomes a contributing factor as this signalled a change in the kind of plants growing across Eurasia.

These new plants not only began to replace the plants that Megaloceros usually ate, they also had a reduced mineral content.

This means that Megaloceros would have had to rely upon a greater amount of reabsorption of minerals from its bones to continually regrow its antlers.

Without the necessary intake of minerals from its diet to replace these used minerals, the bones would have steadily grown weaker and weaker.

With such weakness developing in the skeleton, injuries like broken bones would have become far more common, especially from strenuous activities such as running from predators or fighting other males.

The declining populations also coincide with climate models of the time with Megaloceros first disappearing from areas that were the first to experience climate change, to the very last surviving in areas that were the last to be affected by new environmental conditions.

The theory about human hunting being the sole cause of extinction is no longer considered that plausible.

This is because early humans did not just suddenly appear overnight and commence a wholesale slaughter of animals, they instead evolved and coexisted for several hundred thousand years before Megaloceros went extinct.

Although early humans almost certainly hunted Megaloceros, it’s extremely unlikely that after all this time they would have wiped out the species all by themselves in just a few thousand years considering that there were also other animals to hunt.

Further Reading

- – Origin and Function of ‘Bizarre’ Structures – Antler Size and Skull Size in ‘Irish Elk’, Megaloceros giganteus. – Evolution 28(2): 191-220.Stephen J. Gould – 1974.

- – Notes on Megaloceros luochuanensis (sp. nov.) from Hei-Mugou, Luochuan, Shaanxi province. – Vertebrata PalAsiatica (Gujizhui dongwu yu gurenlei) 20(3):228-235 – X. Xue – 1982.

- – Taphonomy and Herd Structure of the Extinct Irish Elk, Megalocerous giganteus. – Science. New 228 (4697): 340–344. – Anthony Barnosky – 1985.

- – Megaceros or Megaloceros? The nomenclature of the giant deer. – Quaternary Newsletter 52: 14-16. – A. M. Lister – 1987.

- – Fighting behavior of the extinct Irish elk. – Modern Geology 11: 1–28. – A. Kitchener – 1987.

- – Antler growth and extinction of Irish elk. – Evolutionary Ecology Research: 235–249. – Ron Moen, John Pastor & Yosef Cohen – 1999.

- – Antler growth and extinction of Irish Elk. – Evolutionary Ecology Research 1: 235–249 – R. A. Moen, J. Pastor & Y. Cohen – 1999.

- – Survival of the Irish elk into the Holocene. – Nature 405: 753–754. – Silvia Gonzalez, Andrew Kitchener & Adrian Lister – 2000.

- – Pleistocene to Holocene extinction dynamics in giant deer and woolly mammoth. – Nature 431(7009): 684-689 – A. J. Stuart, P.A. Kosintsev, T. F. G. Higham & A. M. Lister – 2004.

- – The phylogenetic position of the giant deer Megaloceros giganteus. – Nature 438 (7069): 850–853. – A. M. Lister, C. J. Edwards, D. A. W. Nock, M. Bunce, I. A. van Pijlen, D. G. Bradley, M. G. Thomas, I. Barnes – 2005.

- – Molecular phylogeny of the extinct giant deer, Megaloceros giganteus. – Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 40(1): 285–291. – Sandrine Hughes, Thomas J. Hayden, Christophe J. Douady, Christelle Tougard, Mietje Germonpr�, Anthony Stuart, Lyudmila Lbova, Ruth F. Carden,Catherine H�nni & Ludovic Say – 2006.

- – Phylogeny of the giant deer with palmate brow tines Megaloceros from west and Sinomegaceros from east Eurasia. – Quaternary International 179 (1): 135–162. – J. van der Made & H. W. Tong – 2008.

- – Getting to the Hart of the Matter: Did Antlers Truly Cause the Extinction of the Irish Elk?. Oikos, (9), 1397. – C. Worman & T. Kimbrell – 2008.

- – The latest Early Pleistocene giant deer Megaloceros novocarthaginiensis n. sp. and the fallow deer “Dama df. vallonnetensis” from Cueva Victoria (Murcia, Spain)”. Mastia. 11–13: 269–323. – Jan Van Der Made – 2015.

- – Deer of the genus Megaloceros (Mammalia, Cervidae) from the Early Pleistocene of Ciscaucasia. – Paleontological Journal. 50 (1): 87–95. – V. V. Titov & A. K. Shvyreva – 2016.

- – The dwarfed “giant deer” Megaloceros matritensis n.sp. from the Middle Pleistocene of Madrid – A descendant of M. savini and contemporary to M. giganteus. – Quaternary International – Jan Van Der Made – 2019.