In Depth

Muttaburrasaurus is one of the best known dinosaurs to come from Australia, though it was the inclusion of Muttaburrasaurus in an episode of the TV series Walking with Dinosaurs that brought it to the attention of a worldwide audience. Muttaburrasaurus is named after the town Muttaburra situated in Queensland, Australia where the holotype remains were first discovered by Doug Langdon in 1963. Although much of the dinosaur was there, some of remains had been taken as souvenirs by the local populace, although many of these were returned when an amnesty for the missing pieces was set up by the local authority. When the remains were finally described in 1981, the type species of Muttaburrasaurus langdoni was established in honour of Doug Langdon.

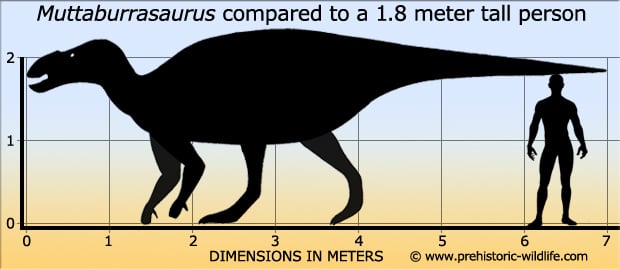

Muttaburrasaurus was an igaunodont dinosaur, group of medium sized herbivores that had their origins back in the Jurassic, whose descendants would become the hadrosaurs of the late Cretaceous. Although often depicted in a bipedal (two legged) pose, Muttaburrasaurus probably spent most of its time in a quadrupedal (all fours) posture. Aside from such a posture being more easily able to support the body proportions, the three middle digits on the ‘hands’ of the forelimbs are joined to form a weight bearing hoof. This adaptation would greatly assist a quadrupedal animal, but be pointless in a bipedal one. However, Muttaburrasaurus could probably still balance and possibly even walk on just their hind legs while reaching up for higher growing plants. This would mostly be possible because of the long tail held stiff by a network of tendons across the vertebrae that acted as a counterbalance to the forequarters of the body. The ability to switch between bipedal and quadrupedal postures as the situation dictated meant that Muttaburrasaurus could potentially browse upon a wide variety of plant types.

An interesting thing about Muttaburrasaurus is that the teeth are suited more towards slicing rather than grinding like in many of its relatives. This led to early speculation by Ralph Molnar that Muttaburrasaurus might have supplemented its diet with meat, possibly by scavenging, though in 1995 Molnar released a new theory suggesting that the teeth were an adaptation convergent to ceratopsian dinosaurs (ones like Triceratops and Styracosaurus that were especially common to Asia and North America). Further support for this convergent evolution comes from the fact that ceratopsians are both distantly yet also more closely related to dinosaurs like Muttaburrsaurus than most other (especially saurischian) types of dinosaurs. Perhaps the most distinctive feature of Muttaburrasaurus is the crest that rises up from the anterior (front) portion of the snout, that may or may not have supported an enlarged mass of soft tissue at this point. This hollow chamber has been interpreted as being for the inclusion of an enlarged nasal cavity to help with smell, though most herbivores do not have to rely upon smell that much when finding food. Another idea that has been suggested is that the crest may have been a form of resonating chamber for amplifying the calls of individuals so that they were louder and carried further over greater distances. More confusion however comes from the observation that in the two currently known Muttaburrasaurus skulls, the crest is slightly different. One skull (the ‘Dunluce skull) has a shorter nasal crest and is slightly older than the holotype which raises the possibility that the crest may have changed in form over this time. Alternatively the difference may be down to the skulls coming from male and female individuals which might suggest a more visual display function. A third alternative is that the second skull may be of a different species to the Muttaburrasaurus type species established by the first skull. Any of these theories and perhaps more than one may one day be proven to be correct, but right now it is hard to be certain without the recovery of new Muttaburrasaurus fossils. On a final note, the nasal crest of Muttaburrasaurus is similar to that of another igaunodontid dinosaur from Mongolia called Altirhinus.

Living during the Albian stage Muttaburrasaurus may have come into contact with sauropods such as Diamantinasaurus, Wintonotitan and Austrosaurus as well as the small ornithopod Atlascopcosaurus while pterosaurs such as Mythunga and Aussiedraco soared through the air on their way to the Eromanga Sea. Additionally Muttaburrasaurus may have been hunted by theropod dinosaurs similar to Australovenator, though so far this specific genus is dated to the earlier Aptian period of the Cretaceous.

Further Reading

– Muttaburrasaurus, a new iguanodontid (Ornithischia: Ornithopoda) dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of Queensland. – Memoirs of the Queensland Museum 20(2):319-349. – A. Bartholomai & R. E. Molnar – 1981. – Possible convergence in the jaw mechanisms of ceratopians and Muttaburrasaurus Ralph E. Molnar – In Sixth Symposium on Mesozoic Terrestrial Ecosystems and Biota, short papers. Beijing: China Ocean Press. pp. 115–117. – A. Sun & Y. Wang (eds). – Observations on the Australian ornithopod dinosaur, Muttaburrasaurus. – Memoirs of the Queensland Museum. 39 (3): 639–652. – Ralph E. Molnar – 1996.