In Depth

Mongolarachne was originally described in 2011 as Nephila jurassica, a prehistoric species of the Nephila genus of orb weaving spiders that we know today. Nephila jurassica made headlines at the time because it was the largest known spider in the fossil record, though comparable in size to modern golden orb weaver spiders that are alive today. It was also credited as being the oldest known species of the Nephila genus, extended the temporal range of the genus back one hundred and thirty million years.

Then two years later a new study by Kuntner et al cast serious doubt upon the fossil spider’s inclusion into the Nephila genus. The main argument against the fossil inclusion into the Nephila genus was that it appeared to be a cribellate spider while known members of the Nephila genus are ecribellate. The difference is that ecribellate spiders spin a sticky silk out of their spinnerets to snare prey like insects. Cribellate spiders have a Cribellum organ different to other spinnerets in that instead of weaving sticky silk, it produces a woolly silk which has a super fine series of fibres that are very effective at trapping insects.

The suggestion that the spider fossils in question were of a cribellate spider lead to new analysis of the specimens with study of a male individual. When the pedipalps (appendages between the fore legs and fangs) of the male specimen were studied they were found to actually have a very different construction to known males of the Nephila genus, and this combined with the identification of the fossils being of a cribellate spider led to only one possible conclusion: the fossils did not represent a species of Nephila. This led to the creation of the Mongolarachne genus, and since normal practice when establishing a genus from a species is to retain the old species name, Nephila jurassica became Mongolarachne jurassica.

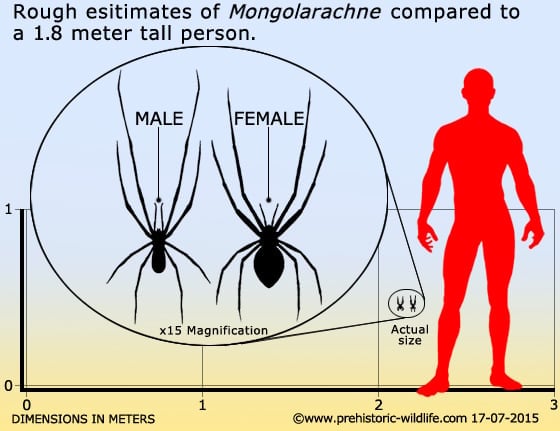

At the time of its description (and time of writing) Mongolarachne jurassica represents the largest fossil spider known to us, and although now known to not be related females of Mongolarachne jurassica are known to comparatively equal to the females of the Nephila genus in size. Like in most spider species, the males of Mongolarachne jurassica are much smaller than the females, and just like with modern spiders, the males may have occasionally been eaten by females when they approached to court them.

When described as Nephila jurassica, Mongolarachne was often reconstructed as sitting within a broad spider web like other orb weaving spiders, though as a cribellate spider such a web construction would be highly unlikely do to the type of silk spun by the spider. Some cribellate spiders don’t spin silk for prey capture, instead preferring to chase prey down, while others spin tangle webs to ensnare passing insects, while other still use he silk to reinforce a burrow so that they can leap out at passing insects that pass a sensory silk line (usually monitored by the spider keeping a foot on the line so it can feel vibrations along it).

Some cribellate spiders however have a very elaborate method of prey capture, spinning a net like web and casting it over their prey. This might be a plausible method of hunting for Mongolarachne since it is morphological similar to these ‘net casting’ spiders. Woolly silk stretches well and when allowed to shrink back to size will trap and snare almost anything that is within it. Some spiders will stretch this net over their prey and allow it to collapse while others will stretch it out between their legs, scoop up their prey into the net and then bring their legs in to trap the prey in the net.

It is impossible to say if this was the hunting method for Mongolarachne as it is impossible for us to see one hunting in the wild, but as a cribellate spider, we can at least have a better idea about it. In addition, most cribellate spiders seem to be either nocturnal, or preferring to reside in dark areas such as caves and cervices in trees or amongst rocks. This would mean that Mongolarachne were probably hidden away from potential predators such as small dinosaurs during the day.

Further Reading

- A golden orb-weaver spider (Araneae: Nephilidae: Nephila) from the Middle Jurassic of China. Biology Letters 7 (5): 775–8 - P. A. Seldon, C. K. Shih & D. Ren - 2011. - A molecular phylogeny of nephilid spiders: Evolutionary history of a model lineage”. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 69 (3): 961–979 - M. Kuntner, M. A. Arnedo, P. Trontelj, T. Lokovše & I.Agnarsson - 2013. - A giant spider from the Jurassic of China reveals greater diversity of the orbicularian stem group. Naturwissenschaften 100 (12): 1171–1181 - P. A. Seldon, C. K. Shih & D. Ren - 2013.