In Depth

The name Mastodonsaurus means ‘breast tooth lizard’, and this came about from the observation of G. F. Jaegar who was describing a broken tooth. Later, when other teeth of Mastodonsaurus were found they were found to be no different from the teeth of most other temnospondyls.

The signature features of Mastodonsaurus are the two teeth in the front of the lower jaw that have enlarged to the point of becoming tusks. These are so large that there are two openings in the upper jaw which these tusks fit through when the mouth is closed. Without these openings the mouth simply would not be able to close fully due to the size of the tusks. These tusks may have been for prey capture, allowing a Mastodonsaurus to get a grip upon prey. However, other temnospondyls seem to have managed just fine without these specialisations, so they may have also served a display purpose that allowed Mastodonsaurus to differentiate between themselves and similar temnospondyls.

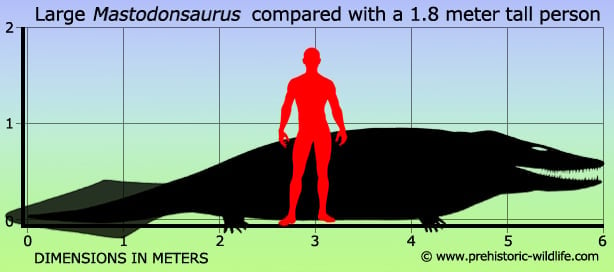

Mastodonsaurus seems to have been a genus that spent most if not indeed all of its time in the water. The evidence for this is quite compelling, but we’ll begin with noted observations of the body. The head of Mastodonsaurus was so large that it took up almost a quarter of the total body length, something that would have been very cumbersome if on land. The eyes are situated midway on top of the skull, which meant that they were best placed for looking up at whatever may have been swimming above them. Sensory sulci that formed a lateral line of sensory organs were also present, and this would have allowed a Mastodonsaurus to pick up upon changes in water pressure caused by the movement of other aquatic animals. Finally for the body, the limbs were greatly reduced in size, and would have been incapable of lifting the body clear off the ground if out of the water. The joints of these limbs are also particularly weak, in turn suggesting limited muscles.

Further support for an entirely aquatic lifestyle comes from the discoveries of several Mastodonsaurus that seem to have died together after the body of water that they were living in dried out. Had they been able to walk about well on land, they should have at least wandered around for a bit searching for another water source. Coprolites associated with Mastodonsaurus are also mostly composed of fish remains, a prey source that would only be abundant within water.

With all of these factors combined, it seems very likely that Mastodonsaurus were restricted to a lifetime in the water. The wide distribution of the genus across Europe might be explained by individuals using ancient river systems to get around, and perhaps spreading into new areas when these rivers flooded, granting temporary access to new locations, as well as possibly creating traps as new bodies of water were isolated when the flood waters receded, but were not replenished by subsequent floods before they dried out. While the limbs were weak, they were likely plenty strong enough for aquatic life where the weight of the body would have been supported by the water. So it is more likely that the limbs were used for locomotion along the bottom, pushing through dense aquatic plants, to even steering by gentle paddling. Also, while fish seem to have been the main prey source for Mastodonsaurus, there are bones from other temnospondyl amphibians that bear tooth marks seemingly created by the teeth of creatures that had teeth similar to Mastodonsaurus. With this in mind it is possible that Mastodonsaurus may have occasionally hunted other temnospondyl amphibians, or they were quite aggressive in defending their territories against competition from other species.

There have been a great many species assigned to the Mastodonsaurus genus over the years, though at the time of writing only three are considered to be valid. Some of the other former species are now considered to be synonymous to these, while other species have been assigned to different genera. As such, some fossils formerly assigned to Mastodonsaurus have now been moved to Capitosaurus, Cyclotosaurus, Eupelor, Heptasaurus, Parotosuchus, Plagiosternum and Stenotosaurus. Further species such as M. andriani, M. indicus, M. laniarius, M. lavisi, M. meyeri, M. pachygnathus and M. silesiacus are considered to be based upon remains that are so indeterminate that their placement within the genus is highly questionable.

Further Reading

- �ber die fossile Reptilien, welche in W�rtemberg aufgefunden worden sind - G. F. Jaeger - 1828. - Comparative osteology of Mastodonsaurus giganteus (Jaeger, 1828) from the Middle Triassic (Lettenkeuper: Longobardian) of Germany (Baden-W�rttemberg, Bayern, Th�ringen) - R. R. Schoch - 1999. - Revision of the type material and nomenclature of Mastodonsaurus giganteus (Jaeger) (Temnospondyli) from the middle Triassic of Germany - Markus Moser & Rainer Schoch - 2007.