In Depth About Mammut

Prehistoric elephants of the genus Mammut are actually more popularly known as ‘mastodons’. The name mastodon means ‘nipple tooth’ and is a reference to the lumpy projections on top of the tooth crown. The name mastodon is today considered an obsolete term for the mammoth genus, yet it is still has a more common occurrence in popular media than Mammut.

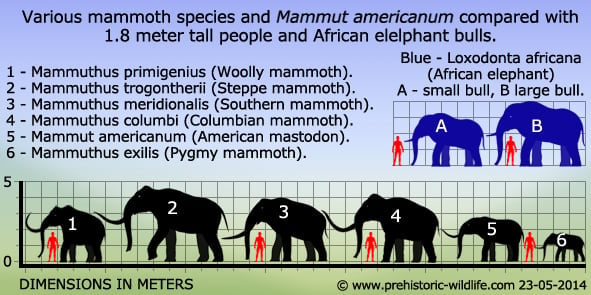

Mammut can and often are confused with mammoths, even though these two groups of proboscids are actually only distantly related. Mammut are usually distinguished by their more robust (heavily built) skeletons and skulls.

Additionally the skulls of Mammut are flatter than the rounded skulls of mammoths. Some Mammut species however have been found with fur which indicates that they were actually hairy, although probably without the thicker under layer seen in mammoths.

Another difference is that mammoths were adapted for grazing grass whereas the teeth of Mammut had lower crowns with knobbled cusps better for processing soft vegetation, which means that Mammut were browsers of bushes and trees.

This is corroborated by fossil evidence that reveals Mammut regularly roamed around spruce forests, although they do also occasionally appear in other habitats. Further similarities to mammoths are the large tusks that curve upwards, although not to the extent of the mammoths.

These tusks of Mammut are up to five meters long although one tusk is often just a bit shorter than the other. There also seems to be sexual dimorphism as well since female Mammut had lower tusks while males had tusks which were higher.

Male Mammut would have fought each other for mating rights to females by pushing each other with their heads and tusks. Analyses of male tusks support this since they show damage to what would have been the base of the tusk when it was forced down from the impact with a competing rival.

These contests were annual occurrences with the strongest males (called bulls) winning the rights to pass on their genes to the next generation of Mammut.

Because elephants are known to have long gestation periods, Mammut probably also did and with this in mind mating probably occurred at a time of year where gestation would continue over the winter months so that the young were born when food was approaching the point of its most plentiful and weather conditions were warmest. When this occurred however would depend upon the exact gestation period of Mammut which currently can only be guessed at.

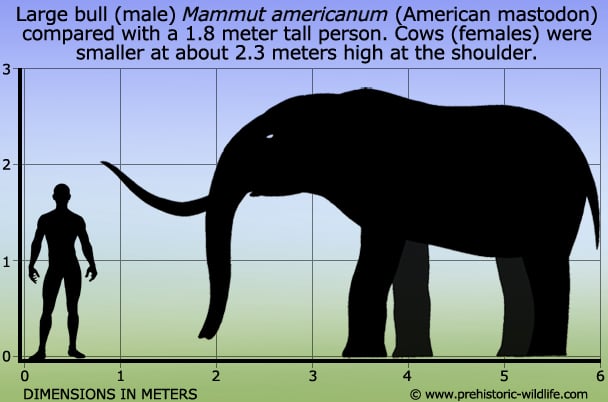

Mammut species had an incredibly broad range across both time and the globe and even though the ultimately went extinct, these species belonged to one of the most successful genera of mammals ever known. The most famous of these species is M. americanum (often known as the American mastodon) was also one of the last species to live.

Although they managed to spread across much of the globe, Mammut do not seem to have taken part in the Great American Interchange, an event where North and South American animals intermixed for the first time after the creation of a permanent land bridge (the Isthmus of Panama) between the Americas.

South American remains that were once considered to have been those of Mammut have now been assigned to the gomphothere elephants Cuvieronius and Stegomastodon.

The exact extinction date for Mammut is hard to establish, but most older sources cite the end of the Pleistocene as the time that they and much of the other Megafauna disappeared.

However more modern analysis of Mammut remains, including radiocarbon dating has now revealed that Mammut may have still been roaming North America between 5000 and 4000 BP (before present). The precise cause for this extinction is still unknown but there are some theories that try to explain it.

One of the most common and plausible theories is the climate change that occurred at the end of the Pleistocene which saw the last major glaciation, however with remains dated to several thousand years ago this is unlikely to be the sole cause.

Early humans are known to have hunted mammoths and elephants, but it’s hard to imagine how a relatively small population of humans could wipe out all the Mammut and most of the other Megafauna over just a few thousand years. Another clue is analysis of fossils that reveal living Mammut suffered from the diseases such as tuberculosis.

Anyone of these things could and would have contributed to a reduction in total population numbers, but probably not to the point where the entire population was wiped out.

However when you stack all of these factors up together you end up with a sequence of events that are just as devastating as single major event such as something like an asteroid or a comet hitting the planet or even a super-volcanic eruption. Here the picture would be diseases such as tuberculosis keeping a cap on the population (the more individuals, the more likely a disease can spread) and harder times such as glaciations stressing the population further.

Mammut could cope with these circumstances, they had done for many millions of years, but with the new factor of human hunting appearing towards the end of the Pleistocene, it was one additional factor too many for them to survive.

Further Reading

- – Mammalian fauna of the upper Juntura Formation, the black butte local fauna. in The Juntura Basin: Studies in Earth History and Paleoecology. – Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 53 (1): 77. – J. A. Shotwell & D. E. Russel – 1963.

- – A Late Cenozoic Vertebrate Fauna from the Coso Mountains, Inyo County, California. – Carnegie Institution of Washington Publication 483 (3): 77–109. – J. R. Schultz – 1937.

- – Intestinal Contents of a late Pleistocene Mastodont from Midcontinental North America. – Quaternary Research 36: 120–125. – Lepper et al. – 1991.

- – The oldest Mammut (Mammalia: Proboscidea) from New Mexico. – New Mexico Geology: 10–12. – Spencer G. Lucas & Gary S. Morgan – 1999.

- – The American Mastodon Mammut americanum in Mexico. – O. J. Polaco, J. Arroyo-Cabrales, M. E. Corona J. G. L�pez-Oliva – In Cavarretta, G. Gioia, P. Mussi, M. et al. The World of Elephants – Proceedings of the 1st International Congress, Rome October 16–20, 2001. Rome: Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche – 2001.

- – Mammoth (Mammuthus spp.) and American mastodont (Mammut americanum) bonesites: what do the differences mean? – Advances in Mammoth Research 9: 185–204. – G. Haynes & J. Klimowicz – 2003.

- – The Overmyer Mastodon (Mammut americanum) from Fulton County, Indiana. – The American Midland Naturalist 159 (1): 125–146. – N. Woodman – 2008.

- – Fossil Proboscidea from the Upper Cenozoic of Central America: Taxonomy, Evolutionary and Pelobiogeographic Significance. – Revista Geol�gica de Am�rica Central. 42: 9–42. – Spencer G. Lucas & Guillermo E. Alvarado – 2010.

- – Regional variation in the browsing diet of Pleistocene Mammut americanum (Mammalia, Proboscidea) as recorded by dental microwear textures. – Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 487: 59–70. – J. L. Green, L. R. G. DeSantis & G. J. Smith – 2017.

- – Mammut pacificus sp. nov., a newly recognized species of mastodon from the Pleistocene of western North America. – PeerJ. 7: e 6614. – A. C. Dooley, E. Scott, J. Green, K. B. Springer, B. S. Dooley & G. J. Smith – 2019.

- – American mastodon mitochondrial genomes suggest multiple dispersal events in response to Pleistocene climate oscillations. – Nature Communications. 11 (1): 4048. – Emil Karpinski, Dirk Hackenberger, Grant Zazula, Chris Widga, Ana T. Duggan, G. Brian Golding, Melanie Kuch, Jennifer Klunk, Christopher N. Jass, Pam Groves, Patrick Druckenmiller, Blaine W. Schubert, Joaquin Arroyo-Cabrales, William F. Simpson, John W. Hoganson, Daniel C. Fisher, Simon Y. W. Ho, Ross D. E. MacPhee, & Hendrik N. Poinar – 2020.