In Depth

When first described the prehistoric whale Livyatan was actually named Leviathan after the biblical sea monster. Unfortunately however Leviathan had already been used to name a mastodon now known as Mammut (Leviathan is actually a synonym to this genus, but still cannot be used). As such the Hebrew word for Leviathan, Livyatan, is now used to refer to this ancient whale. The species name, L. melvillei is in honour of the author Herman Melville, the man who wrote the world famous novel ‘Moby Dick’.

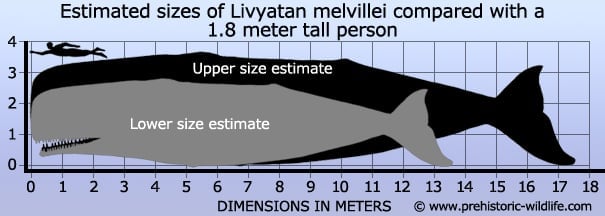

Because only the skull is known, Livyatan is often compared to the sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus) when piecing together the rest of the body. This has yielded size estimates of thirteen and a half meters which make Livyatan a comparable size to the megatoothed sharks like Carcharocles angustidens. However Livyatan has also been compared to another prehistoric whale named Zygophyseter, and this resulted in an estimate of seventeen and a half meters. If accurate then this would make Livyatan comparable to even C. megalodon, the largest shark to ever swim the ocean. In fact for a time both Livyatan and C. megalodon would have swam in the same oceans.

Not only was Livyatan an apex predator like C. megalodon, it probably fed upon the same prey animals which were medium sized baleen whales. Smaller juvenile Livyatan may have preferred proportionately smaller prey items like the smaller cetaceans or even large fish. With teeth that were thirty-six centimetres long, Livyatan had the dentition to take down large prey items. In fact not only were the teeth of Livyatan considerably larger than C. megalodon teeth, they are considered to be the largest known teeth for the purpose of eating. Granted some animals like elephant have modified teeth that form tusks which are even bigger, but they are useless for processing food in the mouth so in this case they do not count as the largest. Livyatan also had teeth in both the upper and lower jaws for grasping prey (the modern sperm whale, the closest living analogy to Livyatan, only has teeth on the lower jaw).

How Livyatan hunted it still a matter of debate, but given its large mouth and teeth it may have used a similar method to kill smaller whales as C. megalodon did. This could be approaching from the bottom and slamming into its target from underneath. An associated method could also be trapping the smaller whale’s rib cage in its jaws and crushing the ribs to create fatal injuries to the internal organs. Another method could see Livyatan holding down a whale beneath the surface to stop it surfacing for air. This is a strategy that would be potentially risky for Livyatan as it too would still need to surface to breathe air, but assuming Livyatan could hold its breath for longer than its prey, it would still be a viable strategy.

Livyatan is morphologically similar to the modern sperm whale, and this has brought comparisons between the two for head function. Livyatan is thought to have had a spermaceti organ that would have been filled with wax and oil. This has also inferred the possibility that Livyatan may have used echolocation to find its prey.

Further Reading

– Corrigendum: The giant bite of a new raptorial sperm whale from the Miocene epoch of Peru. – Nature 466:1134. – O. Lambert, G. Bianucci, K. Post, C. Muizon, R. Salas-Gismondi, M. Urbina & J. Reumer – 2010. – Distribution of fossil marine vertebrates in Cerro Colorado, the type locality of the giant raptorial sperm whale Livyatan melvillei (Miocene, Pisco Formation, Peru). – Journal of Maps. 12 (3): 543. – G. Bianucci, C. Di Celma, W. Landini, K. Post, C. Tinelli & C. de Muizon – 2015. – First record of a macroraptorial sperm whale (Cetacea, Physeteroidea) from the Miocene of Argentina. – Revista Brasileira de Paleontologia. 21 (3): 276–280. – David Sebasti�n Piazza, Federico Lisandro Agnolin & Sergio Lucero – 2018. – Early Pliocene fossil cetaceans from Hondeklip Bay, Namaqualand, South Africa. – Historical Biology: 1–20. – R. Govender – 2019.