Discovery and Early Reconstruction of Iguanodon

Iguanodon has a firm place within dinosaur history books, not just because of the large expanse of fossil material attributed to it, but because it was the second dinosaur to ever be identified and named. The first dinosaur was actually Megalosaurus which was named a year earlier, and back then the term dinosaur didn’t even exist.

The exact discovery of Iguanodon has become something of a popular story, but with successive retelling some of the details have become a little blurred. The main area of this is just who discovered the first Iguanodon teeth, one Gideon Mantell, or his wife Mary Ann.

Gideon Mantell was a practising obstetrician and the popular version of this story is that his wife Mary Ann discovered the first teeth in a quarry in Whiteman’s Green, Sussex while he was visiting a patient in 1822.

However a statement by Gideon Mantell himself in 1851 stated that it was he who had found the original teeth. Mantell’s notes dating back to 1820 also show that he had discovered other material as well as different teeth from what we would call today a carnivorous theropod.

There is also a mention of the discovery of teeth that seem to have belonged to a herbivore. This is why who discovered the Iguanodon teeth varies depending upon who is telling the story.

Initially the teeth were a secondary concern for Mantell as he was more concerned about the reconstruction of the bones and theropod teeth.

Back then the idea of animals like dinosaurs had not yet been conceived and so bones like these were usually taken as being part of an animal similar to those alive at the time. In this case Mantell thought that he was dealing with a crocodile because of the shape of the carnivorous teeth.

The herbivore teeth were however considered by Mantell to belong to a different but possibly equally massive reptile.

In 1822 the herbivore teeth were submitted to the Geological Society of London, but the response was not positive as the members declared the teeth to belong to either a rhinoceros or possibly a fish.

Interestingly one of these members was William Buckland, who under two years later would actually go on to name the first dinosaur, Megalosaurus. Just over a year after this in 1823, Charles Lyell showed some of the teeth to Georges Cuvier, A French naturalist who used techniques of comparative anatomy to identify fossil animals.

One of Cuvier’s most famous successes was that he was the first person to correctly identify the pterosaur Pterodactylus as a flying reptile. Initially Cuvier had the same conclusion as the Geological society in that the teeth were of a rhinoceros, but the next day he actually doubted that interpretation. Unfortunately Lyell’s communication to Mantell only contained Cuvier’s initial opinion of the teeth, something that resulted in Mantell putting the teeth to one side.

William Buckland’s 1824 description of Megalosaurus sent shock waves throughout the scientific community and caused many to start thinking about the kinds of animals that once lived and how they could be different.

Buckland himself visited Mantell soon after to look at his collection of bones and realised immediately that Mantell had a creature that appeared to be similar to Megalosaurus. The idea of giant ‘lizards’ like Megalosaurus being carnivores was still fresh in the head however, and Buckland still insisted that what Mantell had was a carnivore and not a herbivore.

At least encouraged by Buckland’s identification of the bones, Mantell sent the herbivore teeth to Cuvier so that he may have a second opportunity to examine them. Cuvier remembered his doubts after initially declaring the teeth to be those of a rhinoceros, and this time his interpretation was very different.

Cuvier replied and confirmed to Mantell that the teeth were reptilian, and could be those of a herbivore.

On top of this Cuvier printed a public retraction of his first interpretation and confirmed that he now believed the teeth to be reptilian, not mammalian. Georges Cuvier was a highly respected scientist in natural history circles and when he spoke, others stopped and listened.

With the weight of Cuvier’s reputation behind him, Mantell now found himself widely accepted and began to piece together the extinct animal, specifically searching for a living reptile that had similar teeth. Mantell’s answer was supplied by Samuel Stutchbury, assistant-curator of the Royal College of Surgeons. Stuctchbury had recently worked on an iguana and saw a close match with the teeth. Now that Mantell had a close match he began his reconstruction.

The obvious thing to him, and probably most others of the time, was to scale the size of the iguana tooth to the fossil tooth to see how many times larger the fossil was. Mantell then measured the body of the iguana and then multiplied this by how many times the fossil tooth was larger than an iguana tooth.

The result of this was a colossal eighteen meters long, even bigger than Megalosaurus. Needless to say that this was a gross overestimate, and while versions of this technique are still used today, they are strictly restricted to animals that are known to have at least the same body shape.

The similarity of the fossil to the iguana teeth was the inspiration for the name, although Mantell’s first choice was actually Iguanasaurus which translates to ‘iguana lizard’. However as Mantell’s friend William Daniel Conybeare pointed out the iguana is a lizard, and the name might course confusion between the animals. He then suggested Iguanoides which means ‘iguana like’ and Iguanodon, which means ‘iguana tooth’. As you have probably already gathered, Mantell chose Iguanodon.

Mantell acquired a more complete specimen in 1834 which was a partial individual on a bed of rock. Dubbed the Maidstone skeleton (after where it was recovered) this specimen also included Iguanodon’s famous thumb spike, although Mantell’s idea was very different.

Mantell believed the spikes correct place was actually on top of the end of Iguanodon’s snout. The overall body shape of early restorations was also very iguana-like with a low quadrupedal body, fore and hind limbs being the same size as one another and a long trailing tail. This depiction continued until Richard Owen began work upon reconstructing and classifying these animals.

Owen was a staunch supporter of creationism and rejected the teachings of transmutation, the theory that was the precursor to Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution. Owen created the dinosaur group from Megalosaurus, Iguanodon and Hylaeosaurus, but rather than depicting them as reptiles, Owen perceived them to be more mammal-like. Under Owen’s thinking this was an argument against evolution as mammal-like creatures could not evolve from reptiles (something that today can actually be proven by the existence of synapsids and the later therapsids like Thrinaxodon as well as later forms like Megazostrodon).

Rather than being seen as lizards, dinosaurs were now envisioned as being elephantine creatures with scaly skin and mouths full of sharp teeth. The culmination of this vision were the Crystal Palace dinosaur sculptures built from concrete sculpted around brick and steel frames by Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins, who was guided by Owen in their construction.

Another famous story associated with these sculptures is that Hawkins held a dinner party within the body of the standing Iguanodon sculpture before it was finished, however this party actually took place within the mould that was used to cast the sculpture.

Still, if Richard Owen could appreciate what we know of dinosaurs today he might just kick himself for the entertaining but grossly inaccurate depictions of these ancient animals. Owen was also stickler for giving animals the correct name for their group.

Two examples for this include his attempts to get the prehistoric whale Basilosaurus and the pterosaur Ornithocheirus renamed because the literal translation of their names imply they are different types of animal to what they actually were.

While Owen created the word dinosaur which means ‘terrible lizard’, dinosaurs were not lizards but their own group of reptiles. The saurus part continues to upset some palaeontologists today who prefer to translate it as ‘reptile’ rather than the literal meaning of ‘lizard’.

During this time Gideon Mantell continued to work upon Iguanodon, although Owens growing influence in the developing science of palaeontology saw his own ideas as being more prevalent.

Mantell himself did not live to see the Crystal Palace sculptures, but did in 1849 realise that Owen was wrong in his ideas of dinosaurs being heavy and bulky animals. He also noted the slender fore limbs that would form a key part in deciphering Iguanodon’s true form and possible lifestyle.

In 1878 a collection of bones from at least thirty-eight individual Iguanodon were found within a Belgian coal mine. The mine workers were quick to realise the importance of this discovery and set about recovering as much fossil material as they could which would later be reconstructed by the Belgian palaeontologist Louis Dollo in 1882.

These specimens represented a new and larger species of Iguanodon and were given the species name I. bernissartensis, after the location of the coal mine near Bernissart.

These bones combined to create complete individual animals, and while Mantell thought that Owen’s depictions were wrong, Dollo proved it. Dollo also discovered that the spike that Mantell had placed on the snout actually belonged on the hand where it was the thumb.

The overall depiction of Iguanodon was now of a larger but more light weight animal that stood on its hind legs. However, while Dollo’s reconstruction was more accurate and vastly superior to anything before it, there were still some problems.

The main fault with this reconstruction is that the tail is curved. This is something that would have been impossible in the living animal because ossified tendons along the caudal vertebrae held the tail rigid so that it could not bend. Also the posture of the body was in an almost upright walking position, something that would have also been impossible because of the tails true construction.

Accurate depictions of Iguanodon began to appear in the twentieth century and started to become common in popular depictions such as books and documentaries during the 1980’s and 1990’s.

These show Iguanodon to be a dinosaur that could shift between bipedal and quadrupedal postures, although the back is straight and typically held horizontal to the ground rather than upright walking positions. The tail is now always shown to be straight and carried high off the ground.

Iguanodon as a living animal

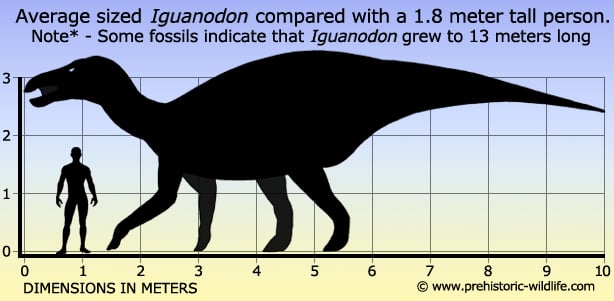

Today Iguanodon is usually depicted as a primarily quadrupedal animal that could comfortably shift to a bipedal posture for high browsing or possibly other purposes. The main argument for this comes not from the overall body shape but the actual construction of the forelimbs.

Firstly these limbs are about three quarters of the total length of the hindlimbs which would result in a fairly comfortable walking gait when fully extended, while the elbow could still be bent to bring the head closer to the ground for easier browsing on low vegetation.

The next bit of Iguanodon’s forelimb specialisation is the hand itself, specifically the five digits. Easiest thing to do here is if you look at the back of your hand and open your fingers up so that you can easily see all five of your digits (four fingers and a thumb).

The centre three digits of Iguanodon’s hand were robust and packed close together. This would be like you putting your three central digits (index, middle and ring fingers) close together so that they were one.

As you may now appreciate this results in an inflexible portion of the hand, but in Iguanodon this was not a problem as it provided the main weight bearing area of the limb when Iguanodon was walking on all fours.

This leaves the thumb which in Iguanodon was just a single large spike.

The remaining fifth digit (your little finger, or ‘pinkie’) was actually very flexible to the point of being prehensile. Easiest way to describe what prehensile means is if you look a picture of a chameleon you may notice that its tail is curved around the branch it is holding on to, this is an extreme case of a prehensile tail. The little finger of Iguanodon however, probably could not flex to this extreme.

The finger was however capable of wrapping itself around a high piece of vegetation so that Iguanodon could pull it down and feed upon parts of a plant that would otherwise have been out of reach.

It is this flexibility of switching between bipedal and quadrupedal posture and feeding on both low and moderately high vegetation that allowed Iguanodon to spread out across a wide area.

Smaller ornithopods would have had to make do with browsing low vegetation and more primitive larger ornithopods would have been more suited to feeding on certain kinds of plants that they could reach.

Iguanodon’s specialisations not only allowed it to compete with other ornithopods but also low browsing armoured dinosaurs like the stegosaurids as well as the smaller sauropods. Being occasionally bipedal even while feeding means that you can see as well as possibly smell further.

This is something that would have given Iguanodon an advantage in spotting predatory dinosaurs sooner than other low browsing dinosaurs were able too.

Early reconstructions of Iguanodon depicted it as ‘tail-dragger’. This was based upon the long held assumption that dinosaurs were really just big lizards and that the tail would have been dragged behind as the animal walked around.

Further studies combined with the discovery of ossified tendons eventually led to the accurate reconstruction of dinosaurs with stiff tails that were carried high off the ground. Ossified tendons are basically regular tendons that have slowly turned to bone over the lifetime of the animal, which is also why these ossified tendons fossilise quite frequently.

One question about these tendons that is sometimes asked is why didn’t Iguanodon just use regular bones instead of tendons? The answer for this question actually goes back to when the Iguanodon was within its egg.

Eggs have to form a protected space where an embryo can develop, while also at the same time be as small as practically possible so that the egg can pass out of the mothers body. If Iguanodon (and other dinosaurs with stiff tails) had bones to support the tail (caudal) vertebrae then the egg would have to be elongated to fit because bones can’t bend. Tendons however can bend, which means the tail could curve around the developing embryo so that it could fit within the smallest space possible.

Upon hatching Iguanodon’s tail would probably have been quite limp and droopy but as the tendons stiffened with age, perhaps as soon as a few days or weeks after hatching, the tail would begin to resemble an adults.

Now that the individual in question did not need a flexible tail the tendons would slowly turn to bone, making the supporting fixture of the vertebrae permanent. Probably the main advantage of having a stiffened tail like this is that it would form a counter balance that would have allowed Iguanodon to more easily switch between quadrupedal and bipedal postures.

The famous teeth of Iguanodon were only present towards the rear of the jaws with the teeth of the lower jaw arranged so that they would rub against the internal sides of the upper teeth.

This rubbing motion would create a shearing action similar to how a pair of scissors work, something which enabled Iguanodon to bite through tougher vegetation. As with all dinosaurs these teeth were constantly replaced throughout the animals entire life, although Iguanodon seems to have had only one spare replacement for each tooth at a time.

Later forms of large ornithopods like the hadrosaurs would develop several replacement teeth. Iguanodon most probably also had cheeks that prevented food from falling out of the sides of the mouth as it was bearing mashed between the teeth.

The front portion of the mouth was toothless which makes the front of the lower jaw resemble a scoop. The front of the upper jaw was similar to form a cropping beak edge, and both were likely covered by keratin to increase durability.

Iguanodon was once thought to have a prehensile tongue like a giraffes, however study of the mouths hyoid bones that support the tongue are very robust, strongly suggesting that Iguanodon could only move its tongue to push food around inside its mouth.

Iguanodon Species and Classification

When Iguanodon was first named by Gideon Mantell in 1825 it was simply named ‘Iguanodon’ with no specific species name. Friedrich Holl created I. anglicum for the holotype of the tooth which had to be changed to I. anglicus for correct grammar. In 1832 Christian Erich Hermann von Meyer named another species I. mantelli which has since been renamed as Dollodon.

The discovery of multiple Iguanodon remains in a coal mine near Bernissart in Belgium resulted in a creation of another species I. bernissartensis by George Albert Boulenger in 1881. Because the holotype I. anglicus is based upon only a tooth it is not considered to be diagnostic enough to identify new species, especially when the teeth of other specimens are not present.

This had led to the establishment of I. bernissartensis as the neotype, which now replaces I. anglicus as the type that all modern fossils are compared to when palaeontologists suspect they may have found Iguanodon remains.

Like other early dinosaurs like Megalosaurus, Iguanodon has suffered from the wastebasket taxon effect resulting in much of the material originally being assigned to it being later found to actually belong the same as other species or even to other dinosaurs.

This is particularly the case for far flung specimens from North America and Asia, but even some European specimens have since been found to actually be other species. Most of the species which are still sometimes mentioned are considered dubious in that they probably do no warrant their own group.

Unfortunately the list varies between individual palaeontologists and resources, and the only ‘safe’ species now is the neotype I. bernissartensis.

American Palaeontologist Edward Drinker Cope created the Iguanodontoidea in 1869 which includes Iguanodon and all dinosaurs thought to be similar to it. Because Iguanodon was the first dinosaur of this group to be named, its name was used as the basis of the group name, something that it standard practice in zoological nomenclature when creating new groups of animals.

Many other ornithopod dinosaurs like the small Dryosaurus and the more medium sized Camptosaurus lie within the Iguanodontidae, but others such as Ouranosaurus that were once thought to be similar to Iguanodon are now regarded as being closer to the later and more advanced hadrosaurs. Dinosaurs in these cases are usually regarded as being distantly related yet still separate from the main group.

Further reading

- – Notice on the Iguanodon, a newly discovered fossil reptile, from the sandstone of Tilgate forest, in Sussex. – Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society 115: 179–186. – Gideon A. Mantell – 1825.

- – Discovery of the bones of the Iguanodon in a quarry of Kentish Rag (a limestone belonging to the Lower Greensand Formation) near Maidstone, Kent – Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal 17: 200–201. – Gideon A. Mantell – 1834.

- – On the structure of the jaws and teeth of the Iguanodon. – Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 138: 183–202. – Gideon A. Mantell – 1848.

- – On the ornithoidichnites of the Wealden – Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London 10: 456–464. – Samuel H. Beckles – 1854.

- – Monograph on the Fossil Reptilia of the Wealden and Purbeck Formations. Part IV. Dinosauria (Hylaeosaurus) – Paleontographical Society Monograph 10: 1–26. – Richard Owen – 1858.

- – Première note sur les dinosauriens de Bernissart. – Bulletin du Musée Royal d’Histoire Naturelle de Belgique 1: 161–180 – Louis Dollo – 1882.

- – Note sur les restes de dinosauriens recontrés dans le Crétacé Supérieur de la Belgique. – Bulletin du Musée Royal d’Histoire Naturelle de Belgique 2: 205–221 – Louis Dollo – 1883.

- – Note on a new Wealden iguanodont and other dinosaurs. – Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London 44: 46–61. – Richard Lydekker – 1888.

- – On the skeleton of Iguanodon atherfieldensis sp. nov., from the Wealden Shales of Atherfield (Isle of Wight) – Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London 81 (2): 1–61 – R. W. Hooley – 1925.

- – The cheeks of ornithischian dinosaurs. – Lethaia 6: 67–89. – Peter M. Galton – 1973.

- – On the ornithischian dinosaur Iguanodon bernissartensis of Bernissart (Belgium). – Mémoires de l’Institut Royal des Sciences Naturelles de Belgique 178: 1–105. – David B, Norman – 1980.

- – On the anatomy of Iguanodon atherfieldensis (Ornithischia: Ornithopoda). – Bulletin de L’institut Royal des Sciences Naturelles de Belgique Sciences de la Terre 56: 281–372 – David B. Norman – 1986.

- – A mass-accumulation of vertebrates from the Lower Cretaceous of Nehden (Sauerland), West Germany. – Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences 230 (1259): 215–255. – David B. Norman – 1987.

- – The first indisputable remains of Iguanodon (Ornithischia: Ornithopoda) from North America: Iguanodon lakotaensis, sp. nov. – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 9 (1): 56–66. – David B. Weishampel & Phillip R. Bjork – 1989.

- – Bernissart’s Iguanodon: the case for “fresh” versus “old” dinosaur bone. – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 23 (Supplement to Number 3): 45A. – A. de Ricqlès – 2003.

- – Identification of proteinaceous material in the bone of the dinosaur Iguanodon – Connective Tissue Research 44 (Suppl. 1): 41–46. – Graham Embery, Angela C. Milner, Rachel J. Waddington, Rachel C. Hall, Martin S. Langley & Anna M. Milan – 2003.

- – A revised taxonomy of the iguanodont dinosaur genera and species. – Cretaceous Research 29 (2): 192–216. – Gregory S. Paul – 2008.

- – Early and “Middle” Cretaceous Iguanodonts in Time and Space. – Journal of Iberian Geology 36 (2): 145–164. – K .Carpenter & Y. Ishida – 2010.

- – On the ornithoidichnites of the Wealden – Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London 10: 456–464. – Samuel H. Beckles – 1854. – Andrew T. McDonald – 2012.