In Depth

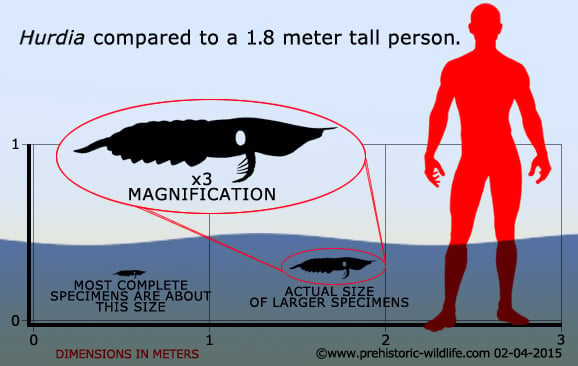

Hurdia is one of the best recognised of all the anomalocaridid genera, thanks mostly to the large number of specimens that have been found. The feature that makes Hurdia really stand out is the enlarged head that has puzzled many researchers to its purpose. There is no need for such a feature in terms of protection, there simply isn’t enough within to protect. However wider studies in associated anomalocaridid genera may yet yield new ideas about Hurdia, which we’ll come to later in the text.

Hurdia has often been described as a predator in popular science, but really this assumption is based more upon the familial link of Hurdia to the famous Anomalocaris which is usually dubbed ‘the’ apex predator of the Cambrian oceans. Though both are anomalocaridids, Hurdia actually has a very different body plant to that of Anomalocaris, specifically the head. The main feeding appendages are also much smaller than those of Anomalocaris as well as proportionately weaker. This leads to the conclusion that Hurdia simply could not rip other arthropods apart like Anomalocaris is often shown to do.

A clearer picture of the ecological adaptations of Hurdia may actually come about from the 2015 description of a new genus of anomalocaridid named Aegirocassis. Although much larger than Hurdia. Aegirocassis has a very similar body form to Hurdia, so much so that the two genera are classified together into the same sub family of anomalocaridid, the Hudiidae. Aegirocassis is thought to have been a filter feeder, and this raises the question, was Hurdia also a filter feeder? This would explain the relative weakness of the limbs of Hurdia given that to filter feed an animal would not need especially strong appendages. Filter feeding would also mean that Hurdia was not competing with more actively predatory anomalocaridids, meaning that it could live in the same ecosystems as them.

The fact that two (and probably more to come) separate genera of anomalocaridid can have greatly enlarged head shields would certainly suggest familiar connection, but again to what purpose. A simple answer could be that the head size and shape was an indicator for a specific genus and species, allowing members of the same species to recognise others of their own kind. Or perhaps as a filter feeder, the shape of the head somehow allowed planktonic organisms to be funnelled towards the appendages where they could catch a greater concentration of organisms for easier feeding. Alternatively there may be a combination of factors, some of which we simply do not know about yet.

The description of Aegirocassis made researchers of Cambrian life, particularly those who study anomalocaridids sit up because the most ground breaking thing about it was that Aegirocassis was proven to have two rows of swimming flaps down the main body. Before this time anomalocaridids were thought to have lost one row of flaps earlier on, but this has caused a rethink in other anomalocaridid studies. The describers of Aegirocassis also commented upon Hurdia as well as the genus Peytoia and by comparison to the Aegirocassis specimens, identified the presence of two rows of swimming flaps on both Hurdia and Peytoia as well.

Further Reading

- The Burgess Shale anomalocaridid Hurdia and its significance for early euarthropod evolution. - Science 323 (5921): 1597–1600. - Allison C. Daley, Graham E. Budd, Jean-Bernard Caron, Gregory D. Edgecombe & Desmond Collins - 2009. - Morphology and systematics of the anomalocaridid arthropod Hurdia from the Middle Cambrian of British Columbia and Utah. - Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology vol 11, issue 7. - Allison C. Daley, Graham E. Budd & Jean-Bernard Caron - 2013. - Anomalocaridid trunk limb homology revealed by a giant filter-feeder with paired flaps. - Nature. - Peter Van Roy, Allison C. Daley & Derek E. G. Briggs - 2015.