In Depth

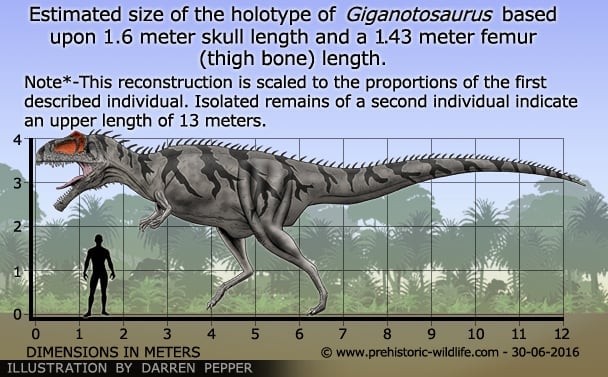

Giganotosaurus made headlines around the world when it was discovered simply for the fact that it was a carnivorous dinosaur that was bigger than Tyrannosaurus. Although the current estimate of Giganotosaurus has it approaching a length of thirteen meters, analysis of a dentary from a second individual suggests that it could grow even bigger.

It’s is not known exactly how Giganotosaurus grew so large as to find out you would need multiple specimens representing different life stages, and right now these specimens are just not known. Tyrannosaur remains by contrast are very numerous and consistently show that they lived the first few years of their lives growing relatively slowly. After several years they would suddenly start a rapid rate of growth reaching almost full size within the space of around ten years, slowing only when they reached reproductive maturity.

It must be remembered that Giganotosaurus was not a member of the tyrannosaurids but of a separate group of theropods, the carcharodontosaurids. But for the sake of speculation, if Giganotosaurus underwent a similar growth cycle, it would either had to of been an even more extreme rate of growth, or lived for even longer than the tyrannosaurids, or maybe even a combination of the two.

The fenestrae are proportionately large in the skull of Giganotosaurus, presumably to reduce the overall weight of its massive skull, currently the largest amongst the known theropods. Inside the skull are the usual areas and attachments for powerful biting muscles but also for a potentially well-developed olfactory region, indicating a good sense of smell.

The teeth of Giganotosaurus are flat and serrated to enable it to easily slice through the flesh of its prey. These kinds of teeth are commonly seen in the carcharodontosaurids, which is why the group is sometimes called ‘shark toothed lizards’. This has led to the proposed hunting strategy of Giganotosaurus targeting the large South American titanosaurs such as Argentinosaurus. Whereas some carnivores could easily crunch through the bones of their prey, the bones of Argentinosaurus are simply too large. Even a large theropod would have trouble just getting its mouth around a femur. So instead, Giganotosaurus adapted to leave the bones and concentrate on just the softer tissue. A series of withering bites could in theory be applied to the legs and underside by just raking its teeth across the flesh. Then all Giganotosaurus would have to do is wait for either blood loss or infection to finish the job. It’s also possible that Giganotosaurus targeted the leg muscles to try and sever a tendon, cutting the muscle free from the bone. This would cripple a large titanosaur so that it had absolutley no chance of escape.

One Giganotosaurus probably would not have been able to tackle a large individual of Argentinosaurus and may have focused its attention upon younger and smaller members. However another dinosaur named Mapusaurus was found not too far away from the Giganotosaurus remains, and raised eyebrows at the time because not one but seven individuals were found together. This has led to some speculating that Mapusaurus could have attacked the larger sauropods as a group, significantly increasing their chances of success. It cannot be said if such behaviour was true for Giganotosaurus, but Mapusaurus was very similar to it, and was discovered not too far away. Further discoveries may yield more clues to the diet and hunting strategy.

Further Reading

– A new giant carnivorous dinosaur from the Cretaceous of Patagonia. – Nature 377: 225-226 – R. Coria & L. Salgado. – 1995. – New specimen of Giganotosaurus carolinii (Coria & Salgado, 1995), supports it as the largest theropod ever found – Gaia, 15: 117–122 – J. O. Calvo & R. A. Coria – 1998. – Braincase of Giganotosaurus carolinii (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of Argentina. – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 22(4): 802-811. – R. A. Coria & P. J. Currie – 2002. – My theropod is bigger than yours…or not: estimating body size from skull length in theropods – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 27 (1): 108–115 – F. Therrien & D. M. Henderson – 2007. – Cranial endocast of the carcharodontosaurid theropod Giganotosaurus carolinii Coria & Salgado, 1995 – Neues Jahrbuch fuer Geologie & Palaeontologie, Abhandlungen 258(2): 249-256 – A. P. Carabajal & J.I. Canale – 2010.