In Depth

The body of Gerrothorax is flattened to the extreme and is one of the morphological features that indicate Gerrothorax lived at the bottom of aquatic habitats such as lakes and rivers. The eyes of Gerrothorax are placed on top of the head in an orientation that really would only provide upwards vision. Rather than moving around by sight, Gerrothorax seems to have used this vision to locate prey that was swimming above.

Living on the bottom would make it difficult for any animal to open its lower jaw without scraping the bottom. Gerrothorax seems to have avoided this problem completely by tilting its head and opening its upper jaw instead. This also infers a specialised hunting strategy using lures to attract prey. For this purpose Gerrothorax most probably had at least camouflaged patterning across its body to allow it to blend in with the bottom, something that would not only hide it from prey, but also from possible predators. Once Gerrothorax realised that prey was available it would open its mouth, the inside of which was probably camouflaged as well with the exception for a brightly coloured lure. Gerrothorax could then use such a lure by moving it about to look like a worm which would then attract the attention of fish and smaller amphibians that were themselves looking for prey. Once close all Gerrothorax would have to do is bring its upper jaw down to trap its prey.

While there are no fossils to confirm the presence of a lure in Gerrothorax, this hunting strategy can be observed today in the alligator snapping turtle (Macrochelys temminkii) which has a brightly coloured appendage that looks like a worm on the tip of its tongue. The turtle lies completely motionless with the exception of wriggling its lure until a fish swims towards its mouth with the intent of eating the ‘worm’. Once the fish come too close the turtle lunges forward with its head and snaps its sharp jaws around the fish.

Another interesting thing about Gerrothorax is the retention of larval stage gills. These gills were situated directly behind the head and arranged into three pairs. There are known to be a permanent feature of adult animals because they were actually supported by bone. It is possible that the gills were sometimes placed behind the broad head to both protect them from damage as well as hide them from view. The retention of these gills, a feature known as neoteny, also means that Gerrothorax probably spent most if not all of its life within the water.

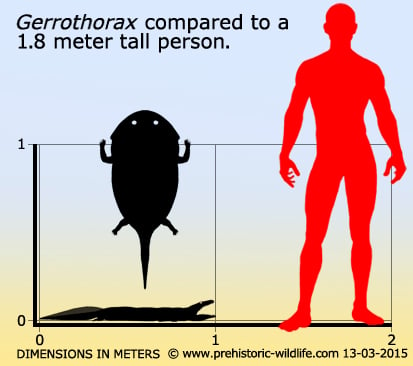

Needless to say that the gills allowed for a greater amount of oxygen to be absorbed from the water, by doing so Gerrothorax may have been able to survive in water with lower oxygen content. They may have also helped Gerrothorax to attain it large one meter length, as even though amphibians absorb oxygen through their skin, and Gerrothorax did have a proportionately large skin surface to body mass ratio, the lower body would have been in regular contact with the bottom of its environment. It’s possible that this contact restricted the even flow of water over its body, as well as the presence of features for the purpose of camouflage and protection that hampered its ability to process oxygen from above, necessitating the presence of external gills.

The retention of juvenile stage gills can also be seen in the much smaller amphibian Microbachis from the Permian, which itself resembles a modern day axolotl.

Further Reading

– Gerrothorax pulcherrimus from the Upper Triassic Fleming Fjord Formation of East Greenland and a reassessment of head lifting in temnospondyl feeding. – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 28 (4): 935–950. – Farish A. Jenkins Jr, Neil H. Shubin, Stephen M. Gatesy & Anne Warren – 2008. – Braincase, palatoquadrate and ear region of the plagiosaurid Gerrothorax pulcherrimus from the Middle Triassic of Germany. – Palaeontology 55 (1): 35–50. – F. Witzmann, R. R. Schoch, A. Hilger & N. Kardjilov – 2011. – Cranial morphology of the plagiosaurid Gerrothorax pulcherrimus as an extreme example of evolutionary stasis. – Lethaia vol45, issue 3, pp 371-385 – Rainer R. Schoch & Florian Witzmann – 2011. – Reconstruction of cranial and hyobranchial muscles in the Triassic temnospondyl Gerrothorax provides evidence for akinetic suction feeding. – Journal of Morphology. 274 (5): 525–542. – Florian Witzmann & Rainer R. Schoch – 2012.