In Depth

Gryposaurus has a long standing and convoluted association with the genus Kritosaurus to the point that in the 1920‘s Gryposaurus was actually regarded as a synonym to Kritosaurus. Later study has since interpreted Gryposaurus as a distinct genus, but this thinking has had the effect of emptying most of the known material for Kritosaurus into Gryposaurus. Also the idea of Gryposaurus and Kritosaurus being the same is still questioned by many palaeontologists on the grounds that Kritosaurus is known from only partial remains that seem to differ from Gryposaurus in terms of geographical location.

Past speculation around the 1970s to 1980 also suggests that Gryposaurus and Kritosaurus might be synonyms of Hadrosaurus, though by the 1990s they were once again regarded as being different because of differences in the ilium (one of the bones of the pelvis) and the upper arms. Further fossils and research might one day call for Gryposaurus to be re-synonymised with Kritosaurus, but for the time being at least Gryposaurus and the species attributed to it are treated as valid.

The technical classification for Gryposaurus is that it is a saurolophine hadrosaurid. Though older texts still describe Gryposaurus as a hadrosaurine, this is no longer in common use since Hadrosaurus was found to be different from other genera previously labelled as hadrosaurines. Because of this Hadrosaurus was given its own place beneath the Hadrosauridae, but the term Hadrosaurinae had to be disbanded because it no longer contained the genus Hadrosaurus. From here the next oldest genus of the group, Saurolophus, was established as the type genus of the group now known as the Saurolophinae, and hence why Gryposaurus is currently classed as a saurolophine.

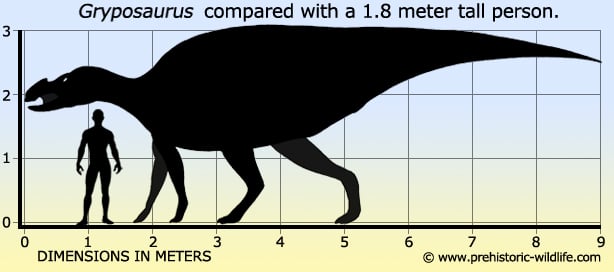

Gryposaurus is of course also known as a duck billed dinosaur because of the specially adapted mouth that was suited for snipping vegetation. Once a mouthful was obtained, the rear tooth batteries went to work grinding the teeth in a fashion that was similar to chewing yet different to how we and animals chew today. Instead of a flexible lower jaw, the upper jaws are believed by many palaeontologists to have come away from the skull so that the upper and lower teeth could slide over each other and grind the plant matter. There is still a lot of contention as to exactly which kinds of plants hadrosaurids ate, with popular ideas suggesting soft aquatic plants while fossil evidence actually points to tougher terrestrial plants that do not normally grow in wetland ecosystems. An obvious advantage that Gryposaurus and other hadrosaurid dinosaurs had however was the ability to shift between quadrupedal and bipedal postures, and ability that allowed them to either feed low down to the ground, or as much as a few meters above it.

Many fossil locations of Gryposaurus coincide with areas that would have been near the coast of the Western Interior Seaway, a shallow Cretaceous sea that submerged most of North America from the Gulf of Mexico all the way up to the Arctic Ocean. These areas would have been areas of wetlands, swamps, marshes and river deltas, though these do not necessarily have to be the only ecosystems that Gryposaurus was active in, just the one supported by fossil evidence.

As a saurolophine hadrosaurid, Gryposaurus lacked an elaborate hollow crest that is the signature feature of the lambeosaurine hadrosaurids. Instead the nasal arch of the skull bowed upwards to produce and arch over an enlarged nasal opening, something that has been interpreted as a possible housing for large amounts of soft tissue. If this interpretation is correct, then Gryposaurus might have had a display feature made up from soft tissue rather than the hollow bony crests of the lambeosaurines. Additionally the nasal arch in some skulls has a rough texture which might indicate the presence of a keratinous growth and possible extension of the feature by further keratin or even cartilage. Although not directly related, many pterosaurs are also known to have had skull crests constructed in a similar fashion where a keratinous crest attached to a skull via and enlarged bony growth to help anchor it in place.

Further Reading

- On Gryposaurus notabilis, a new genus and species of trachodont dinosaur from the Belly River Formation of Alberta, with a description of the skull of Chasmosaurus belli, Lawrence M. Lambe - 1914. - Upper Cretaceous dinosaurs from the Bearpaw Shale (marine) of south-central Montana with a checklist of Upper Cretaceous dinosaur remains from marine sediments in North America, J. R. Horner, 1979. - A new species of Gryposaurus (Dinosauria: Hadrosauridae) from the late Campanian Kaiparowits Formation, southern Utah, USA, Terry A. Gates & Scott D. Sampson - 2007. – The braincase and skull roof of Gryposaurus notabilis (Dinosauria, Hadrosauridae), with a taxonomic revision of the genus. – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 30 (3): 838–854. – Alberto Prieto–Marquez – 2010.