In Depth

Gorgonops is the type genus of the Gorgonopsia, though paradoxically it is not the best represented by fossil remains. Gorgonops was a therapsid, a kind of creature more derived than a therapsid, yet still much more primitive than mammals which would eventually evolve from them. Because of the mammal lineage there has been several suggestions that Gorgonops and relative genera may have had warm blooded metabolisms and hence a possible covering of hair. Unfortunately these ideas remain speculation as so far no proof to prove, or indeed disprove, the warm-blooded theory exists. What is known however is that our definitions of cold and warm-blooded animals have changed somewhat thanks to new and more precise study techniques, so it could also be possible that Gorgonops might have had something between a ‘cold’ and a ‘warm’ blooded metabolism, yet again, this is only speculation at this point.

Relative to body size, Gorgonops had a deep skull which had a triangular profile when viewed from above. Perhaps the most distinctive features were two enlarged canine teeth that were so big they almost protruded beyond the lower jaw. To help protect these teeth, the lower jaws grew in such a shape so that the anterior (front) portion was thicker than the posterior (rear) portion. This form would have protected the enlarged canine teeth from accidental damage, and was similar in bone function to the flanges of bone of some false sabre-toothed cats (nimravids and barbourofelids) and sabre-toothed cats (machairodonts) that would live over two-hundred million years later.

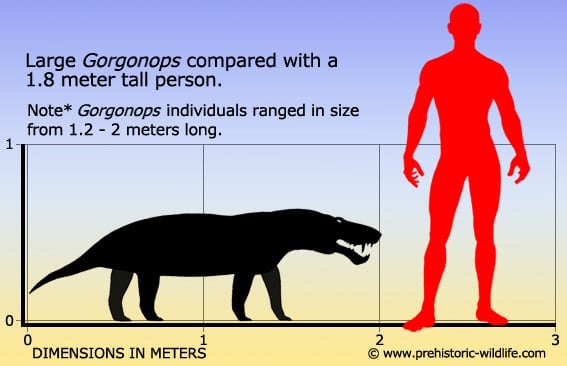

Gorgonops would have been one of the key predators across southern Africa during the Permian, and here we look at the teeth again. Because the canines were so large, they would have had little trouble in penetrating the tough hides of some of herbivores of the time, particularly pareiasaurs such as Bradysaurus. Aside from the teeth, one of the key predatory advantages that Gorgonops had over prey were that the legs supported the body from below rather than sprawling out to the sides like in most prey animals of the time. Aside from allowing for more energy efficient locomotion, the legs would have also allowed for a much faster pace. What animals were hunted however would depend upon the size of the individual Gorgonops, and there were some quite broad differences between species in terms of size.

There are three species of Gorgonops that are widely recognised amongst the majority of researchers, and these are the type species G. torvus as well as G. longifrons and G. whaitsi. The species are usually differentiated by skull features such as G. torvus having a proportionately longer snout, the skull of G. whaitsi being wider at the rear and G. longifrons having a longer snout and larger orbital fenestra (opening in the skull for the eye) than G. whaitsi. Aside from allowing for identification of species, the differences might denote slight variations towards differing hunting between species, with some specialising in different prey and/or modes of prey capture.

There are three other species at the time of writing that are not always recognised for different reasons. G. kaiseri is known from a single incomplete skull which has a rear narrower than other species and a slightly higher snout, but the lack of overall preservation means that it cannot be confidently assigned to Gorgonops to quell all doubt. Likewise, G. dixeyi is named from a partial skull that has been flattened during its fossilisation. Finally G. eupachygnathus was named from a partial and flattened skull of what may have actually been a juvenile of another already named species, particularly G. torvus, or G. whaitsi. Unfortunately, since no clear determination can be made to either species, so G. eupachygnathus continues to be listed even though it is probably a synonym to one of the other two species.

Further Reading

Further reading- Investigations in South African fossil reptiles and amphibia. 7. On some new gorgonopsians. – Annals of the South African Museum 12:82-90. – S. H. Haughton – 1915. - Therapsids from the Permian Chiweta Beds and the age of the Karoo Supergroup in Malawi - L. L. Jacobs, D. A. Winkler, K. D. Newman, E. M. Gomani, & A. Deino - 2005.