In Depth

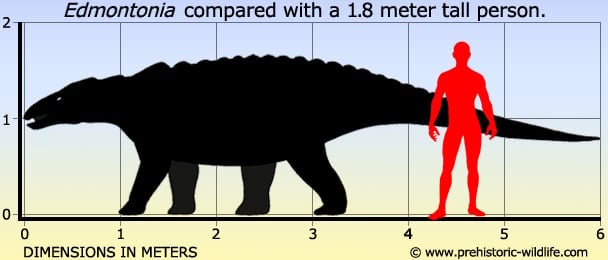

Edmontonia was one of the larger nodasaurids, dinosaurs that were similar to the ankylosaurids but lacked their tail clubs and had narrower mouths. Still, Edmontonia did possess armour plates called osteoderms along its back, and is particularly noted for having large spikes that point out from the sides of its body, the four largest of which are above the shoulder. It seems unlikely that these spines were just for defence as they only cover a relatively small part of the body, and they may not have provided all that much protection against large theropod dinosaurs such as tyrannosaurs like Daspletosaurus and Albertosaurus.

It’s plausible that these shoulder spikes may have been more like deer antlers, with the larger and more developed spikes belonging to the more mature individuals. Additionally it is possible that two Edmontonia may have walked up to one another and engaged in a pushing contest for dominance, the horns locking so that the Edmontonia could get a grip of one another. Again larger spikes would have been preferable in such a contest as they would have allowed the more mature individuals a reach advantage.

Study of other fossils found in association with Edmontonia, specifically petrified trees, has come to the conclusion that Edmontonia lived in an environment that saw extended wet and dry periods throughout the year. This would suggest that like other animals in similar climates, Edmontonia would lay eggs to hatch in time for the wet season so that the newly hatched young had a plentiful supply of fresh vegetation. Additionally the adults would have spent much of their time feeding upon as many plants as they could so that they could build up fat reserves to better survive the lean periods of the dry seasons. The oncoming of the wet season is also thought to be the reason why some Edmontonia remains have the spikes and armour in exactly the same position as they were in life. This is simply a case of flood water washing a large amount of sediment over an individual that had died during the dry season, burying and protecting it from carnivorous animals that may have scavenged and pulled the body to pieces had it not been buried from them. Additional fossil material has been assigned to the Edmontonia genus from other genera. A skull and partial skeleton from Palaeoscincus (originally assigned to the genus as P. rugosidens) was assigned to Edmontonia to create the species E. rugosidens. Additionally another genus, Denversaurus schlessmani, has been declared a synonym to Edmontonia, with the material forming the basis for another new species, E. schlessmani. However the validity of some material belonging to Edmontonia has also been questioned, one case in point being the fossils identified as the species Edmontonia australis now generally considered to belong to the genus Glyptodontopelta. Additionally the palaeontologist Robert T. Bakker proposed in 1988 that the species E. rugosidens should be renamed Chassternbergia and be made a subgenus, although this has not come into common usage by other palaeontologists who still prefer to treat E. rugosidens as a species of the Edmontonia genus.

Further Reading

– Edmontonia rugosidens (Gilmore), an armored dinosaur from the Belly River Series of Alberta. – University of Toronto Studies, Geology Series 43: 3-2. – L. S. Russel – 1940. – Review of the Late Cretaceous nodosauroid Dinosauria: Denversaurus schlessmani, a new armor-plated dinosaur from the Latest Cretaceous of South Dakota, the last survivor of the nodosaurians, with comments on Stegosaur-Nodosaur relationships. – Hunteria 1(3):1-23.(1988). – R. T. bakker – 1988. – Edmontonia – In The Age of Dinosaurs. Publications International, LTD. p. 141. ISBN 0-7853-0443-6. – Peter Dodson, Brooks Britt, Kenneth Carpenter, Catherine A. Forster, David D.Gillette, Mark A. Norell, & George Olshevsky & Michael J. Parrish & David B. Weishampel. – New information on the cranial anatomy of Edmontonia rugosidens Gilmore, a Late Cretaceous nodosaurid dinosaur from Dinosaur Provincial Park, Alberta. – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 26 (4): 1011–1013. – Matthew K. Vickaryous – 2006.