In Depth

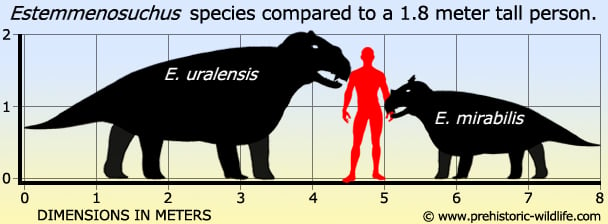

Although other herbivorous therapsids like Styracocephalus also had head crests, Estemmenosuchus had by far the most elaborate head ornamentation. These crests varied between the two species, but superficially the head ornamentation resembled short deer antlers. The horns of Estemmenosuchus grow upwards from the frontal skull bones and seem to have primarily been display devices.

As with many of the therapsids the exact diet of Estemmenosuchus is still a subject of debate amongst palaeontologists. Some have pointed to the sharp canines and incisors and declared Estemmenosuchus to be a carnivore. However many of the herbivorous tharapsids still support carnivore like teeth, and the sheer bulk and size of the body suggest that it was shaped to incorporate a large digestive system. As a general rule herbivores have larger bodies to accommodate a longer and more complex digestive system because plant matter takes longer to digest than animal meat. This is why most palaeontologists consider Estemmenosuchus to be a herbivore, although some concede that it may have supplemented its plant diet with meat and if this were true, then Estemmenosuchus would be an omnivore.

Another piece of evidence to support the herbivore theory is how the legs are orientated. The rear legs are situated directly under the hips supporting the body weight from underneath. By themselves this would suggest that Estemmenosuchus spent a lot of time walking as it would provide a more energy efficient form of locomotion. The front legs however sprawl out to the sides similar to how you see them in modern lizards. While this has been suggested to improve manoeuvring so that the head ornamentation is pointed towards a rival Estemmenosuchus, or even a potential predator, a more obvious benefit is that these legs would allow Estemmenosuchus to lift its forward upper body up and down, kind of like it was doing push ups. This pairing of different limb attachments would suit a herbivore better than a carnivore because it would still allow for more efficient walking when Estemmenosuchus searched for suitable food, while also allowing Estemmenosuchus to lower its head to the ground for easier low level browsing.

The large size and bulk of Estemmenosuchus have also brought the suggestion that Estemmenosuchus was gigantothermic. This is where an animal has a low surface area to body mass ratio resulting in the outer tissue layers insulating the inner layers. This increases the base temperature of the animal giving it a metabolism close to a warm blooded creature without the usual adaptations that would suggest it was warm blooded.

Further Reading

– Diagnosen der Therapsida des oberen Perm von Ezhovo [Diagnoses of Therapsida of the Upper Permian of Ezhovo]. – Paleontologischeskii Zhural, 1960, n. 4, p. 81-94. – P. K. Chudinov – 1960. – New facts about the Fauna of the Late Permian of the U.S.S.R. – Journal of Geology, v. 73, p. 117-130. – P. K. Chudinov – 1965. – Estemmenosuchus and primitive theriodonts from the Late Permian. – Paleontological Journal 34 (2): 184–192 – M. F. Ivakhnenko – 2000. – Tetrapods from the East European Placket—Late Paleozoic Natural Territorial Complex.. – Proceedings of the Paleontological Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences 283: 200. – M. F. Ivakhnenko – 2001.