In Depth

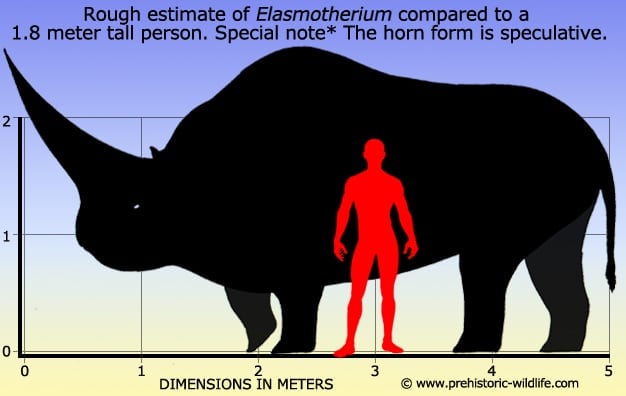

Elasmotherium is one of the a typical animals that represents Pleistocene era fauna, though there has been a lot of debate over not only how it lived but what it really looked like One problematic area concerning the study of Elasmotherium is the actual morphology of the genus. Some reconstructions consider Elasmotherium to have been similar to modern rhinos and be set quite low to the ground, while other reconstructions give Elasmotherium a more horse-like appearance, in part due to the long legs of the animal.

A second area of contention about Elasmotherium is the not only the shape and size of the horn. But whether one even existed. No horn core is known to exist despite multiple cranial remains, yet the best preserved individuals d show a boss (round dome) growth on bone on the skull where the horn would be expected to be. If Elasmotherium did not have a horn then they still would have had a low round protuberance on their heads. If Elasmotherium however did have horns, and it’s quite likely that they did, then these horns would have been made out of keratin, the same material that your fingernails are made of. Unfortunately keratin does not preserve like bone, and in time decomposes like flesh, which means that even with a best guess by comparison to other similar animals, we still do not know what shape or size this horn could have been. Modern reconstructions that you see today are therefore based upon comparison to other Pleistocene era rhinoceroses.

To further complicate the matter about horn form, it should be remembered that there are at the time of writing three recognised species of Elasmotherium. The first Elasmotherium species appeared in the late Pliocene, popularly believed to have been descended from Sinotherium. The oldest species of Elasmotherium are E. caucasicum and E. chaprovicum, both going back as far as the late Pliocene, meaning that both species existed at the same time as one another. Two separate species would denote a need to recognise members of their own kind including physical, though slight, variation. Had horns been present, then is quite probable that the horns of the two species would have had differences in form and size, in a similar manner to the ceratopsian dinosaurs of the late Cretaceous. This is not to imply that E. caucasicum and E. chaprovicum coexisted on the same landscapes, merely that they may have occasionally encountered one another and needed to tell the difference. The type species E. sibiricum is better known from the late Pleistocene, but if this species coexisted with an older or as yet undiscovered species, as well as having many more hundreds of thousands of years of evolutionary development, then it’s plausible that a keratinous horn, if present, would again be slightly different from other Elasmotherium species horns.

Another area of debate regarding Elasmotherium is whether they were hairy or not. Again different species of the same genus may require different answers, but so far only teeth and bones of these animals are known, soft tissue and skin material is several lacking. It could be though that there is simply no one good answer and that suggestions that Elasmotherium did or did not have hair may be correct. The Pleistocene period was not one long ice age as it is sometimes incorrectly depicted, but a series of glacial periods when world temperatures dropped and ice sheets spread from the poles, and interglacial periods when world temperatures increased and ice sheets receded back to the poles. All mammals have the ability to grow hair; even rhinos alive in Africa today still have hair though very sparse. During the interglacial periods when temperatures were warmer, Elasmotherium may have had less and/or thinner hair. Conversely, during the glacial periods when world temperatures were cooler, Elasmotherium may have been more hairy than their interglacial ancestors and descendants. Elasmotherium have been depicted as living in a wide variety of environments, though today most palaeontologists agree that Elasmotherium probably lived on open grass plains in mixed scrub, probably switching between the two as they wandered. Elasmotherium are usually depicted as being grazers of grass and low growing vegetation. This is mainly derived from the observation that the teeth are large and have high crowns, a form that is very common to grazing animals that experience high tooth wear from their diets. Grassy plains featuring the occasional area of sparse woodland would have also been very common during this period of the Earth’s history, and most of the successful herbivores of this time evolved to exploit these environments.

Quickly returning to the subject of whether Elasmotherium were hairy or not, living in areas that were exposed to environmental elements may have meant a greater need to develop hair growth. One reason is the obvious that such environments offer very little protection from prevailing winds which can add a significant wind chill factor to existing temperatures in an environment. Another factor, especially during glacial periods is that the air is not just colder, but drier because a much greater proportions of the world’s water is frozen solid as ice. This means a greatly reduced cloud cover which in turn does not trap the warm air that had built up during the day, not only causing a reduction in air temperatures, but freezing what little moisture is on the ground as frost. This would have been particularly true for inland areas such as central Eurasia, which may have furthered the need for Elasmotherium to be hairy.

There are a few areas over which we are a little more certain about Elasmotherium. The front feet of Elasmotherium were larger than the rear. This is significant as the form of the fore quarters shows that the fore legs would have had a greater weight bearing responsibility than the rear legs. Larger fore feet would have reduced ground pressure due to the greater weight being spread over a larger surface area, something that may have helped Elasmotherium to deal with snowy and other soft surface conditions. Cave art that is many thousands of years old also depicts beasts like Elasmotherium that show them to have more bison-like poses than those of horses, something that lends a little of support to modern reconstructions of Elasmotherium being a bit more low slung with their heads held closer to the ground for browsing. One cave in particular at Rouffignac in France shows a primitive drawing of a rhinoceros-like beast that some have interpreted to possibly be an Elasmotherium.

Studies of the limbs of Elasmotherium also suggest that they would have been quite like modern day rhinos in terms of their locomotion. Although it is uncertain how fast they could run given their size and weights, which are variable according to interpretation, it has been recognised that Elasmotherium were at least skeletally capable of an airborne phase during running as in a gallop.

Further Reading

– About the Hyroideum, Sternum and Metacarpale V Bones of Elasmotherium sibiricum Fischer (Rhinocerotidae) - Journal of the Palaeontological Society of India 20: 10–15. - E. I. Belyaeva - 1977. – Diversity and evolutionary trends of the Family Rhinocerotidae (Perissodactyla) - Palaeo (141): 13–34 - Esperenza Cerde�o - 1998. – Middle Miocene elasmotheriine Rhinocerotidae from China and Mongolia: taxonomic revision and phylogenetic relationships - Zoologica Scripta (The Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters) 32 (2): 95–118 - Pierre-Olivier Antoine - 2003. – Limb Bones of Elasmotherium (Rhinocerotidae, Perissodactyla) from Nihewan (Hebei, China) - Vertebrata Palasiatica (in Chinese with English translations) (4): 110–121 - Tao Deng, Ming Zheng - 2005. - On the fossil rhinoceros Elasmotherium (including the collections of the Russian Academy of Sciences) - V. Zhegallo, N. Kalandadze, A. Shapovalov, Z. Bessudnova, N. Noskova, E. Tesakova - 2005. – Relict Mammal Species of the Middle Pleistocene in Late Pleistocene Fauna of the Western Siberia South - Quaternary stratigraphy and paleontology of the Southern Russia: connections between Europe, Africa and Asia: Abstracts of the International INQUA-SEQS Conference (Rostov-on-Don, June 21–26, 2010). Rostov-on-Don: Russian Academy of Science. pp. 78–79 - 2010. – On the importance of the representatives of the genus Elasmotherium (Rhinocerotidae, Mammalia) in the biochronology of the Pleistocene of Eastern Europe. – Quaternary International. 379: 128–134. A. K. Schvyreva – 2015. – Evolution and extinction of the giant rhinoceros Elasmotherium sibiricum sheds light on late Quaternary megafaunal extinctions. – Nature Ecology & Evolution. 3 (1): 31–38. – Pavel Kosintsev, Kieren J. Mitchell, Thibaut Devi�se, Johannes van der Plicht, Margot Kuitems, Ekaterina Petrova, Alexei Tikhonov, Thomas Higham, Daniel Comeskey, Chris Turney, Alan Cooper, Thijs van Kolfschoten, Anthony J. Stuart & Adrian M. Lister – 2018.