In Depth about Dunkleosteus

In modern popular culture, Dunkleosteus is by far the best known and most often represented of the early placoderm carnivores. However Dunkleosteus actually sat within the Dinichthys genus for a long time as the species Dinichthys terrelli.

It was not until the large numbers of Dinichthys remains were re-studied that it was realised that a large number of the Dinichthys fossils actually represented different genera, not species.

The result was that many of these remains were split to form new genera including the creation of Dunkleosteus.

In a further twist however, the species that was split to form Dunkleosteus, D. terrelli, was actually the remains most often used when reconstructing Dinichthys.

Along with the equally giant Titanichthys, Dunkleosteus is one of the largest predatory placoderm fish known in the fossil record.

However unlike Titanichthys which seems to have preferred large quantities of smaller prey items, Dunkleosteus was an apex predator capable of taking down pretty much anything it could clasp its jaws around.

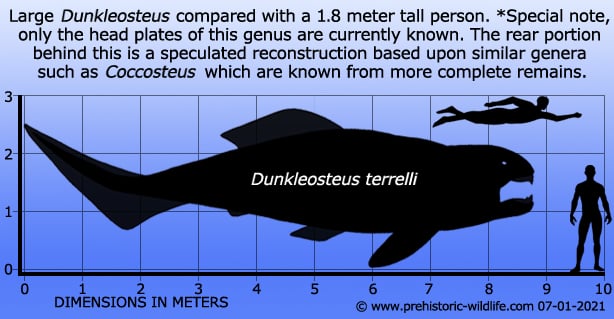

Because only the armoured head of Dunkleosteus is known, it can be problematic to reconstruct the rear portion that was almost certainly unarmoured. This reasoning comes about from the lack of rear fossils for not just Dunkleosteus but all related placoderms that are similar to Dunkleosteus.

The only possible insights come from much smaller placoderms like Coccosteus. With a maximum length approaching only forty centimetres, Coccosteus was positively tiny in comparison to Dunkleosteus, but the impressions of the softer hind body can still be seen in fossils attributed to it.

Smaller animals in general tend to fossilise better and in more complete states because they can get protected from scavengers and the elements more quickly.

Aside from armour, the bony plates of Dunkleosteus could have served two further purposes.

As a predatory placoderm, Dunkleosteus likely attacked other related placoderms that had the same kind of bony plates for protection.

In the absence of a harder organic material, Dunkleosteus would at least need the same material to break through the armour. Shape the material to a sharp bladed edge, and you have a chance of cutting through it.

The second reason is that the jaws need enough driving power to cut and break apart armoured prey, and the only way that this could happen is if Dunkleosteus had incredibly powerful jaw muscles.

However these muscles would in turn require strong supports and attachments otherwise the jaws could not be brought to bear with their full force.

This is likely why Dunkleosteus and other related placoderms like Eastmanosteus retained armoured heads.

Although Dunkleosteus had a powerful bite it was not the strongest amongst fish, that title goes to the gigantic shark C. megalodon that lived several hundred million years later. Still, with a bite force estimated at almost two metric tons, Dunkleosteus could still use its sharp jaws to shear through any prey item it chose.

What prey items were on the menu seem to have been dependent upon the age of the Dunkleosteus in question.

Juvenile Dunkleosteus had stiff jaws best suited for soft bodied prey items.

As Dunkleosteus grew older, the jaws would become more flexible, perhaps to better protect them from injury and breakage when dealing with larger, more powerful and more heavily armoured prey items.

The actual hunting and feeding style of Dunkleosteus is also a popular subject of interest. With the heavy plates around the head, Dunkleosteus was probably not a fast swimmer, but still would have had powerful muscles developed from just swimming around with the weight.

This meant that Dunkleosteus either preferred slower prey, or used ambush tactics to try and take its prey off guard.

Another thing to consider is that the jaws of Dunkleosteus, and probably other similar placoderms, could open exceptionally fast within a fraction of a second.

This would create a sudden void inside the mouth of Dunkleosteus, creating a vacuum that sucked the water and the prey that was swimming in it into its mouth. This means that Dunkleosteus did not have to physically catch its prey, just get close enough to open its mouth.

Larger Dunkleosteus seemed to have preferred other placoderm fish perhaps like Bothriolepis that was very common at the time. Once caught, Dunkleosteus could use its sharp jaws to cut up prey, but it seems that only the softer and more easily digestible flesh was desired.

When Dunkleosteus fossils are found, they are often found in association with fish boluses.

A bolus is a ball of remains that has been chewed and swallowed, but the remains in connection with Dunkleosteus are of only bones that already seem to have been partially digested.

This indicates that Dunkleosteus may have spat out parts that were too hard for it to digest completely, a precedent that is known in numerous other fish.

Finally, because Dunkleosteus was at the top of its food chain, the only other thing that it would have to worry about being attacked by was another Dunkleosteus. This actually does seem to have happened with some Dunkleosteus plates actually showing damage that seems to have been inflicted by the jaws of another Dunkleosteus. Asides from territorial combat, this may indicate active cannibalism in Dunkleosteus.

Further reading

- – Feeding mechanics and bite force modelling of the skull of Dunkleosteus terrelli, an ancient apex predator – Royal Society 3 (1): 77–80 – Philip Anderson & Mark Westneat – 2007.

- – Shape variation between arthrodire morphotypes indicates possible feeding niches – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology volume 28, #4. – Philip S. L. Anderson – 2008.

- – Two new species of Dunkleosteus Lehman, 1956, from the Ohio Shale Formation (USA, Famennian) and the Kettle Point Formation (Canada, Upper Devonian), and a cladistic analysis of the Eubrachythoraci (Placodermi, Arthrodira) – Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 159(1):195-222 – R. K. Carr & W. J. Hlavin – 2010.

- – Ecomorphological inferences in early vertebrates: reconstructing Dunkleosteus terrelli (Arthrodira, Placodermi) caudal fin from palaeoecological data. – PeerJ. 5: e4081. – Humberto G. Ferrón, Carlos Martínez-Pérez & Héctor Botella – 2017.