In Depth

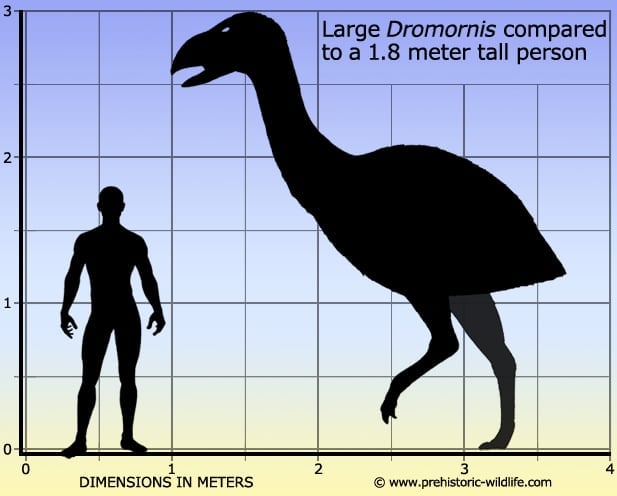

Dromornis is also often referred to by the English translation of its Greek name ‘Thunder bird’, as well as the Aboriginal ‘Mihirung paringmal’ which means ‘giant bird’. Dromornis was certainly a big bird being just a bit shorter but much heavier than the Moa from New Zealand, while being slightly lighter but a bit taller than Aepyornis from Madagascar. The size of Dromornis came at a price however, and the short stubs that are wings confirm that Dromornis was not capable of flying. Such a condition is referred to as being secondarily flightless, as the ancient ancestors of Dromornis would have certainly been flight capable. Although Dromornis may appear to be a much larger and more dangerous version of an ostrich, study of the fossils has revealed that the huge Dromornis was more closely related to geese.

The actual diet of Dromornis remains a subject of debate amongst palaeontologists. The actual skull of Dromornis is only known from fragmentary remains so it is hard to infer diet based upon its description. Body features such as the lack of sharp claws have been taken as signs that Dromornis may have been a herbivore, reaching up into trees to crop vegetation with its beak. However more complete skulls belonging to other members of the groups such as Genyornis suggest that the dromornithids would have been equally capable of killing and eating meat. Another suggestion for Dromornis which can also be applied to others of the group is that they were omnivores, typically feeding from plants, but also supplementing their diet with meat by either hunting small animals or scavenging carrion.

Because Dromornis disappears from the fossil record during the early Pliocene, it most probably never encountered early human settlers (an event that happened during the Tarantian of the Pleistocene up to forty-eight thousand years ago). Because this disappearance occurred this early, it cannot be blamed upon hunting by human settlers and serves to cast doubt on the claim that the disappearance of the Australian megafauna was solely down to human hunting.

Further Reading

– The skull of dromornithid birds: anatomical evidence for their relationship to Anseriformes. – Records of the South Australian Museum 31(1):51-97 – P. F. Murray & D. Megirian – 1998. – The extinct flightless mihirungs (Aves, Dromornithidae): cranial anatomy, a new species, and assessment of Oligo-Miocene lineage diversity. – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. – Trevor H. Worthy, Warren D. Handley, Michael Archer & Suzanne J. Hand – 2016. – Sexual dimorphism in the late Miocene mihirung Dromornis stirtoni (Aves: Dromornithidae) from the Alcoota Local Fauna of central Australia. – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. – W. D. Handley, Chinsamy, A. M. Yates & T. H. Worthy – 2016.