In Depth

When you are presented with an image of a moa bird, chances are you are looking at Dinornis, which internationally is the most famous of the moa.

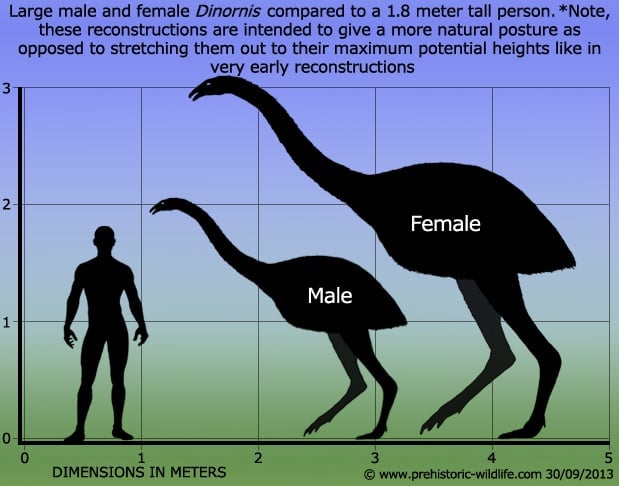

This fame is mostly down to the immense size of Dinornis, individuals of which at full elevation of the neck could reach up to just over three and a half meters high.

Feathers of Dinornis have even been recovered, study of which reveals that in life Dinornis would have been a reddish brown in colour.

However, being secondarily flightless, the feathers had ‘de-evolved’ into more primitive hair-like structures.

These would have provided not only insulation, but a weatherproof coat that kept the skin dry when it rained.

Only the legs as well as parts of the head and throat were devoid of feathers.

Like its relatives, Dinornis had small heads with a beak that curved slightly downwards.

This beak allowed Dinornis to selectively snip off small portions of the most edible plants of the forests that once covered all of New Zealand.

In the past Dinornis has been treated as something of a wastebasket taxon with almost any moa remains being attributed to Dinornis upon their discovery.

This has led to the Dinornis genus previously attaining one of the longest species name lists of any moa, but fortunately, later palaeontologists that inherited moa study from their forebears realised for themselves that something was up.

Later study of Dinornis remains has now seen most of the fossils of former species re-assigned to different moa genera, while a few species such as D. struthioides were found to be synonyms to existing Dinornis species.

At the time of writing there is now just two universally recognised species of Dinornis. These are D. novaezealandiae from the North Island, and D. robustus of South Island.

The Dinornis genus of moa is perhaps the best example of the extreme sexual dimorphism that can be seen in these birds.

The females of Dinornis can be as much as one and a half times taller than the males, and at the same time be almost three times as heavy.

So extreme were these size differences that males and females were once thought to be separate species, with males being classed under D. struthioides, and females under D. robustus.

It was not until the advent of DNA analysis that the truth was discovered and that D. struthioides became a synonym to D. robustus.

DNA analysis of Dinornis specimens has also revealed the presence of two previously unknown lineages within known Dinornis fossils.

This means that in the near future two new species of Dinornis may become listed, but at the time of writing further details on these are unavailable.

The use of DNA analysis in Dinornis however also illustrates how palaeontologists are continually trying out and using techniques originally designed for other scientific areas to help them to understand and reveal more of the truth about long extinct animals.

Unfortunately however, the vast majority of fossils of extinct animals in general do not contain any testable DNA, they have just been fossilised for too long.

Care should be taken not to confuse Dinornis with the similarly named Dromornis from Australia.

Further Reading

- On the remains of Dinornis, an extinct gigantic struthious bird - Richard Owen - 1843.

- Extreme reversed sexual size dimorphism in the extinct New Zealand moa Dinornis - Michael Bruce, Trevor H. Worthy, Tom Ford, Will Hoppitt, Eske Willerslev, Alexei Drummond & Alan Cooper - 2003.

- Nuclear DNA sequences detect species limits in ancient moa - L. Huynen, C. D. Millar, R. P. Scofield & D. M. Lambert - 2003.

- Reconstructing the tempo and mode of evolution in an extinct clade of birds with ancient DNA: The giant moas of New Zealand - Allan J. Baker, Leon J. Huynen, Oliver Haddrath, Craig D. Millar & David M. Lambert - 2005.