In Depth

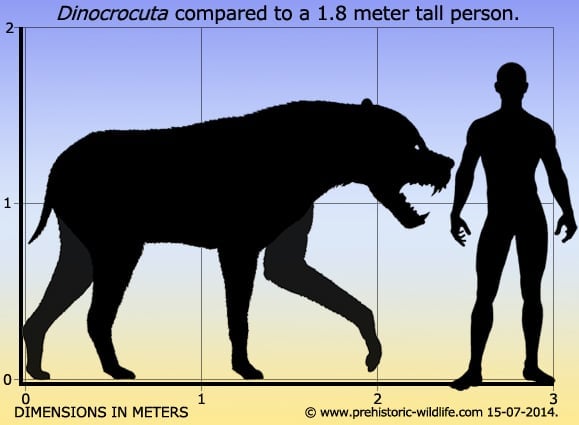

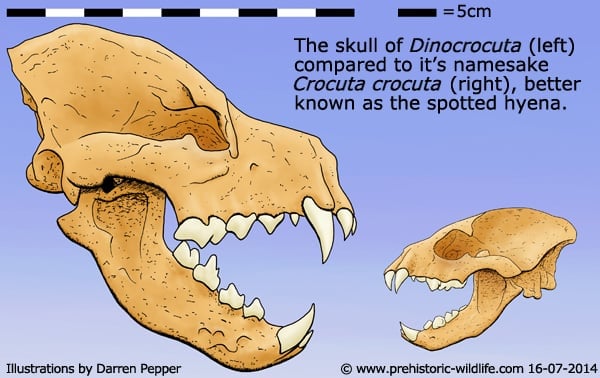

The name Dinocrocuta translates to English as ‘terrible hyena’, with ‘dino meaning terrible and the ‘crocuta’ part being a reference to the Crocuta genus which is home to modern hyenas that we can see alive today. This is born out of a superficial similarity in physical form between modern hyenas and Dinocrocuta, however close study of the genus has seen Dinocrocuta placed within the Percrocutidae, a group that is separate to hyenas, and is closer to felids (cats) and nimravids (false sabre toothed cats). The similarity between Dinocrocuta and modern hyena is therefore another example of an animal adapting to similar survival conditions to occupy an ecological niche. The thing that immediately stands out about Dinocrocuta is the immense skull with its highly robust construction and large teeth. The attachment points for the jaw closing muscles are well developed indicating that the muscles of the head would have been capable of generating bone crushing forces. The teeth of Dinocrocuta are also more conical as opposed to blade-like, something that would have given the teeth much greater resilience when impacting hard objects such as bones.

Dinocrocuta is popularly perceived as fulfilling a similar ecological niche as the modern day hyena, and there is little doubt that Dinocrocuta was capable of crunching through bones to get at the marrow within them. This is a key adaptation for an animal that relies upon scavenging to make up part of its diet since bones may be the only things left by the predators that made the kill. However there is still a popular misconception about the modern hyena being obligate scavengers, that simply isn’t true given the recorded evidence of hyena making their own prey kills, and it would be unreasonable to assume the same for Dinocrocuta. There is even a fossil skull of the prehistoric rhinoceros Chilotherium with tooth marks that closely match the dental pattern of Dinocrocuta. What is significant about these is that the tooth marks have partially healed, indicating that the rhino was alive at the time the bite marks were inflicted and that it survived long enough for the bones to heal. Therefore while this attack was not successful, it is a strong indicator that Dinocrocuta were active predators that supplemented their diets with scavenging, as opposed to being obligate scavengers that waited for other predators to make kills for them.

Further Reading

- The Chinese Neogene mammalian biochronology - its correlation with the European Neogene mammal zonation. In E.H. Lindsay, V. Fahlbusch and P. Mein, eds., European Neogene Mammal Chronology. Plenum Press, New York. pp 527-556. - Z. Qui - 1990. - Cranial function in a late Miocene Dinocrocuta gigantea (Mammalia: Carnivora) revealed by comparative finite element analysis. - Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 96: 51. - Zhijie Jack Tseng - 2008. - Mandibular biomechanics of Crocuta crocuta, Canis lupus, and the late Miocene Dinocrocuta gigantea (Carnivora, Mammalia)”. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 158 (3): 683–696. Zhijie Jack Tseng & Wendy J. Binder - 2010. - Osteological evidence for predatory behaviour of the giant percrocutid (Dinocrocuta gigantea) as an active hunter. - Chinese Science Bulletin 55 (17): 1790–1794. - Tao Deng & Zhijie Jack Tseng - 2010.