In Depth

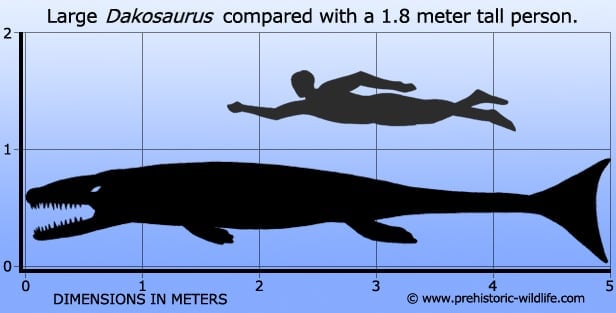

The deep skull of Dakosaurus has led to this marine reptile being nicknamed ‘Godzilla’ in the popular media. However unlike the famous Japanese daikaiju, Dakosaurus was actually a four to five meter long crocodile that was specially adapted for a life at sea. It’s tall and deep skull meant that Dakosaurus was actually quite different from other metriorhynchid crocodiles, and had an even more extreme body form adapted to a marine lifestyle. Whereas Metriorhynchus is now known to have had limbs more like legs rather that ‘paddle-shaped’ flippers, Dakosaurus took the transition to aquatic life even further with developed flippers like other but unrelated marine reptiles. Dakosaurus also had a tail that terminated in a fluke to provide extra propulsion through the water.

Whereas the majority of marine crocodiles seem to have specialised in a piscivorous fish eating lifestyle, Dakosaurus’s skull and jaws combined with the large serrated and laterally compressed teeth, indicate that it was a predator of larger prey items. While this prey may have included large fish, Dakosaurus may have also gone after other marine reptiles that would have required a stronger set of jaws to deal with. While Dakosaurus was a crocodile, it seems to have lived a lifestyle that would become commonplace with the advent of the mosasaurs during the Cretaceous.

Dakosaurus appears to have been active in locations that also had other marine crocodiles swimming in them, the most similar to Dakosaurus being Geosaurus. Comparison between these two marine crocodiles indicates that while no salt gland has been found to be present, Dakosaurus did have a cavity in the location which is known to house salt glands in other crocodiles. A salt gland in itself is an organ that extracts excess sodium from the body which has been absorbed by exposure to living in sea water, and can be found in a variety of animals including other reptiles, birds and even fish. While the evidence for a salt gland in Dakosaurus remains circumstantial, it would be unusual if Dakosaurus did not have one.

The advanced marine adaptations of Dakosaurus have been the subject of a lot of debate about whether Dakosaurus, and also other marine crocodiles could give birth to live young at sea, or if they still had to return to the land to lay eggs. Supporters of the live birth theory point to the fact that no nest sites that can be attributed to Dakosaurus have been found. However, just because the nest sites are not known does not mean that they did or do not exist. If Dakosaurus nested, it may have used high tides to help carry it further up the beach so that it did not have to travel as far on its flippers. If however the live birth theory proves to be correct, then it would be a further testament to the remarkable adaptability that various crocodile species have shown.

Further Reading

– Die Meer-Krocodilier (Thalattosuchia) des oberen Jura unter specieller Ber�cksichtigung von Dacosaurus und Geosaurus – Paleontographica 49: 1-72 – e. Fraas – 1902. – [Marine crocodiles in the Mesozoic of Povolzh’e] – Priroda 1981: 103 – V. G. Ochev – 1981. – An unusual marine crocodyliform from the Jurassic-Cretaceous boundary of Patagonia – Science 311: 70-73 – Z. Gasparini, D. Pol & L. A. Spalletti – 2006. – First occurrence of the genus Dakosaurus (Crocodyliformes, Thalattosuchia) in the Late Jurassic of Mexico – Bulletin de la Societe Geologique de France 178 (5): 391-397 – M. -C. Buchy , W. Stinnesbeck , E. Frey & A. H. G. Gonzalez – 2007. – The evolution and interrelationships of Metriorhynchidae (Crocodyliformes, Thalattosuchia). – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 27 (3): 170A – M. T. Young – 2007. – New occurrence of the genus Dakosaurus (Reptilia, Thalattosuchia) in the Upper Jurassic of north-eastern Mexico with comments upon skull architecture of Dakosaurus and Geosaurus. – Neues Jahrbuch f�r Geologie und Pal�ontologie, Abhandlungen 249 (1): 1-8. – M. -C. Buchy – 2008. – What is Geosaurus? Redescription of Geosaurus giganteus (Thalattosuchia: Metriorhynchidae) from the Upper Jurassic of Bayern, Germany – Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 157: 551-585 – Mark T. Young & Marco Brandalise de Andrade – 2009. – The oldest known metriorhynchid crocodylian from the Middle Jurassic of North-eastern Italy – Neptunidraco ammoniticus gen. et sp. nov”. Gondwana Research 19 (2): 550–565 – Andrea Cau & Federico Fanti – 2011. – Body size estimation and evolution in metriorhynchid crocodylomorphs: implications for species diversification and niche partitioning – Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 163 (4): 1199–1216 – Mark T. Young, Mark A. Bell, Marco Brandalise de Andrade & Stephen L. Brusatte – 2011.