In Depth

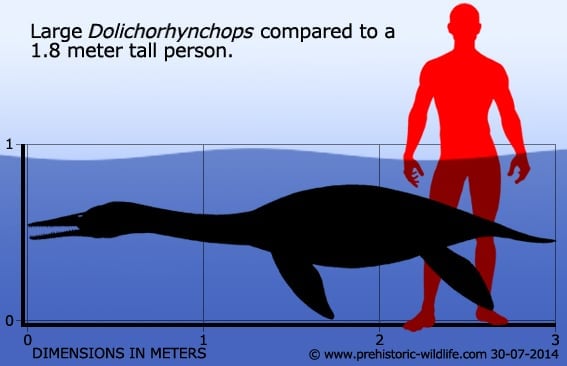

The first Dolichorhynchops specimens were recovered in 1900 by George F. and Charles H. Sternberg from the Smokey Hill Chalk Formation. After being named by Samuel Wendell Williston in 1902, the type specimen has been a regular feature in the display of the Museum of Kansas. The establishment of two additional species (D. herschelensis & D. tropicensis) since this time has indicated that Dolichorhynchops was probably active throughout the Western Interior Seaway when it was at its greatest extent. The general appearance of Dolichorhynchops is similar to that of long necked pliosaurs of the early Jurassic such as Macroplata and Rhomaleosaurus. However closer study of Dolichorhynchops has revealed it to be more closely related to the longer necked plesiosaurs such as Plesiosaurus. This short necked long skulled form is typical of the polycotylid plesiosaurs, and can be seen repeated in other members of this group.

The jaws of Dolichorhynchops are not thought to have had a powerful bite force; however this would be an unnecessary ability as it’s the teeth that would do the work in prey capture. The teeth are long and thin which means that they are best suited for puncturing slippery soft bodied prey. Arranged across the long jaws and getting slightly larger towards the ends they would have provide an extensive area for prey capture, quite similar to some ornithocheirid pterosaurs that are thought to be dedicated hunters of fish.

Unfortunately while long thin teeth like Dolichorhynchops possessed are great for this kind of prey capture, they are not suited for tearing prey into small pieces. Like their plesiosaur cousins, Dolichorhynchops probably swallowed small prey whole, and may even have relied upon swallowing stones for use as gastroliths. These would have allowed Dolichorhynchops to break down hard parts such as scales and bones.

Dolichorhynchops has a possible predator/prey association with the huge mosasaur Tylosaurus. This idea is based upon Charles Sternberg 1918 discovery of a Tylosaurus that had the partially digested remains of a plesiosaur within its stomach area. Later study has revealed that these remains were of a polycotylid plesiosaur, but they have been so well digested by the Tylosaurus that it is impossible to assign them to a specific genus. Also Sternberg noted the presence of a tooth belonging to a shark called Squalicorax found in association with these plesiosaur remains. With this in mind it is possible that this individual Tylosaurus was not the first to the kill, but possibly used its large size to intimidate the other predators into leaving the kill.

This interpretation does not completely dispel the idea that Tylosaurus fed upon Dolichorhynchops, since as it was the apex predator of the Western Interior Sea; Dolichorhynchops would have certainly been on its target list. Also Tylosaurus was not the only predator that was a danger to Dolichorhynchops as late surviving pliosaurs like Brachauchenius would have been present during the early stages of the temporal range of Dolichorhynchops, as well as huge sharks like Cretoxyrhina that were comfortably at least twice the size of Dolichorhynchops and are also known to have attacked marine reptiles. Living in such dangerous waters meant that the best chance that Dolichorhynchops had of avoiding being eaten was to rely upon speed and manoeuvrability.

Further Reading

– Restoration of Dolichorhynchops osborni, a new Cretaceous plesiosaur. – Kansas University Science Bulletin 1(9):241-244 – S. W. Williston – 1902. – Trinacromerum bonneri, new species, last and fastest pliosaur of the Western Interior Seaway. Texas Journal of Science 49(3):179-198. – D. A. Adams – 1997. – A new polycotylid plesiosaur (Reptilia: Sauropterygia) from the Upper Cretaceous Bearpaw Formation in Saskatchewan, Canada. – Journal of Paleontology 79(5):969-980. – T. Sato – 2005. – A new species of polycotylid plesiosaur (Reptilia: Sauropterygia) from the Lower Turonian of Utah: Extending the stratigraphic range of Dolichorhynchops. – Cretaceous Research 34:184-199. – R. Schmeisser McKean – 2012.