In Depth

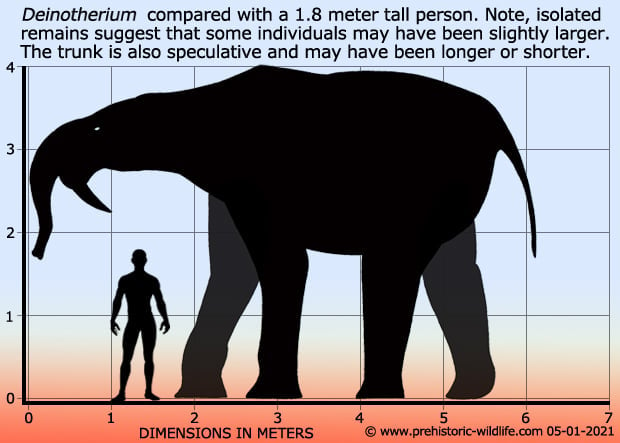

Although the name Deinotherium translates to mean ‘Terrible beast’, this definition somewhat belies the true nature of Deinotherium as a prehistoric elephant. Compared to today’s living elephants however, Deinotherium is the type genus of the more distantly related group called the deinotheres. Deinotherium remains one of the largest elephants in the fossil record, rivalling even the big mammoths such as the huge M. imperator (Imperial mammoth) and being only just beaten by M. sungari. However the latter mammoth species has since been questioned and may yet be shuffled over to M. trogontherii (Steppe mammoth). The only terrestrial mammal confirmed to have been definitively larger than Deinotherium was the gigantic Paraceratherium.

The two things that make Deinotherium stand out from amongst other elephants is the two downward pointing short tusks that are recurved in an arc that sees the tips pointing towards the front feet when the head is carried horizontally level. Not only is this a different direction from the forward pointing tusks of other elephants but the tusks themselves actually emerged from the lower jaw as opposed to the upper of other elephants. The reason and function of this arrangement has baffled palaeontologists since the discovery of this animal, in fact early reconstructions often had the jaw placed upside down so that the tusks looked like they were pointing in the ‘right’ direction.

In elephants and mammoths the tusks are usually used as tools for the purpose of obtaining food. Some popular theories concerning how Deinotherium could use their tusks include digging in the ground for nutritious roots and tubers, hooking the tusks around tree branches where they joined the trunk and snapping them down for easier access to the leaves, to running the tusks down the trunks of trees to strip off the bark. It’s quite possible that the tusks were also display devices where the distinctive shape allowed Deinotherium to recognise others of their genus at a time when many other elephants with exotic tusk arrangements were roaming the land. The thing to remember is that the purpose of the tusks does not necessarily have to be restricted to just one of these functions, and that all of the above are probably more likely than just one. However with the tusks being mounted in the lower jaw, Deinotherium would have likely had a finer degree of control over them.

Deinotherium was not just different in the tusks but had a skull that was short with a flattened top. The nasal opening is enlarged and further back which strongly suggests that the trunk was strong and well developed. Although it is still uncertain how this trunk would appear in life, these adaptations do also suggest that Deinotherium had a greater reliance upon it for manipulating things. The main teeth inside the mouth of Deinotherium were also suitable for both shearing and grinding food which possibly suggests a varied diet.

The type species of Deinotherium, D. giganteum, was first discovered in Europe, but the later discoveries of D. bozasi have revealed an African origin. From here Deinotherium radiated out towards Europe and Asia where it became one of the most successful mammals until the end of the Pliocene. By the start of the Pleistocene the Deinotherium populations of Europe and Asia seem to have disappeared, quite probably as a result of the changing habitats which were brought about by a global change towards a colder climate. The last populations of Deinotherium held out in Africa where they survived until around one million years ago (middle Ionian of the Pleistocene).

Further Reading

– Evolution of feeding mechanisms in the family Deinotheriidae (Mammalia: Proboscidea) – J. M. Harris – 1976. – On a Deinotherium (Proboscidea) finding in the Neogene of Crete. – A. Athanassiou – 2004.