In Depth

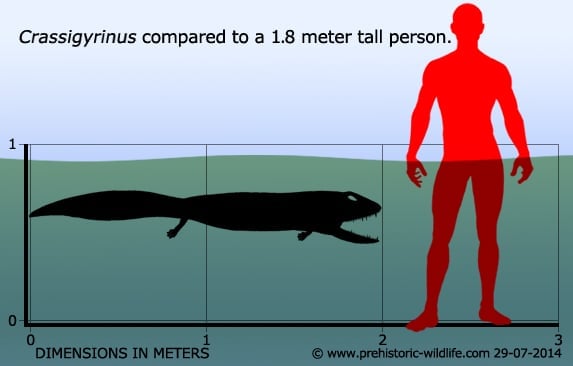

An interesting specimen of an early amphibian as it appears to have completely abandoned terrestrial life in favour of an aquatic lifestyle. Its limbs, especially those at the front, were greatly reduced in size and would have been no use for land locomotion. They would have still served as rudders and may have been used for pushing through dense undergrowth of aquatic plants. It is possible they may also have still been used for mating, allowing a male to hold onto a female during the spawning process, the same way as many modern amphibians do today. Further, the pelvis did not have a solid connection to the spine as can be found in terrestrial vertebrates.

Analysis of the skull reveals a predatory lifestyle. The jaws featured two rows of teeth, including two elongated fangs, perfect for biting into fish. The jaws could also open very wide and appear to have had the supporting muscle structure to inflict very powerful bites, meaning that once Crassigyrinus was clamped on, there was no escape. Further, the snout of the skull had several ridges to it suggesting re-enforcement to cope with the stress of a high bite force. Its plausible that Crassigyrinus needed these adaptations for coping with prey that was also powerful, hinting at a predatory specialisation. The eyes also appear to be enlarged, an adaptation for low ambient light, suggesting either a nocturnal lifestyle or deep water hunting.

The tail is not well known as it is often not preserved very well. Given the size of the small limbs, it may have been large to compensate for them, and from what tail fragments that have been recovered, may have been flattened laterally. Such an adaptation would have provided stable locomotion in the water, as well as sudden bursts of speed.

Crassigyrinus may have favoured the ambush predator approach, instead of just cruising around looking for a snack. A modern day comparison could be made with a freshwater Pike. A Pike has a very stunted tail compared to other fish, but it will often lurk amongst the reeds waiting for prey items to swim close enough to be within striking distance. Once close enough it lines itself up and uses it short but powerful tail to produce a sudden burst of speed at its target. Its wide mouth filled with teeth means that whatever is in front has little chance of getting away, possibly not unlike Crassigyrinus.

Further Reading

– On Crassigyrinus scoticus Watson, a primitive amphibian from the Lower Carboniferous of Scotland. – Palaeontology 16: 179-193. – A. L. Panchen – 1973. – On the amphibian Crassigyrinus scoticus Watson from the Carboniferous of Scotland. – Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B 309, 505-568. – A. L. Panchen – 1985. – The Scottish Carboniferous tetrapod Crassigyrinus scoticus (Lydekker) – cranial anatomy and relationships. – Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh: Earth Sciences. 88, 127-142. – J. A. Clack – 1998.