In Depth

The first ever fossil of Charnia was found in England. It seems that the first time this fossil was recorded was in 1956 when a 15 year old schoolgirl named Tina Ford reported seeing the fossil to her geography teacher. However at the time it was established ‘fact’ that the rocks in the Charnwood forest were far too old to have fossils in them, and were laid down before animals existed, and hence the teacher dismissed Tina’s claims of the fossil. Then a year later in 1957, a schoolboy named Roger Mason (who would go into a career in geology) brought the specimen to the attention of scientists, and in 1958 the fossil was identified and named as a genus of Trevor Ford in 1958.

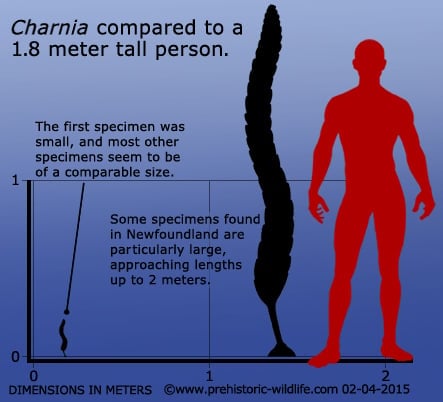

Charnia without doubt is one of the oldest lifeforms that we know about that once lived on our planet. Though resembling a frond of a fern, as well as perceived to be an alga or even a sea pen when in the early days of its study, the majority of modern day researchers are certain that Charnia was more likely a different kind of lifeform, though one unlike anything we currently know about today, as well as a member of a group that at this time does not seem to have had any surviving descendants.

The discovery of Charnia marked the first time that a living organism was found in rocks that that were older than the Cambrian period. Before this discovery it was unthinkable by scientists at the time that fossils could be found in rocks that were then loosely termed as Precambrian. In addition to this there also so far does not seem to have been any survival of Charnia beyond the Ediacaran period. Unless living examples are one day discovered in future deep sea exploration, then it would seem that Charnia represents an evolutionary dead end.

There is much still to learn about how Charnia lived. Analysis of fossil beds where Charnia has been found has led to many people concluding that Charnia lived in very deep water, so deep in fact that sunlight would have been unable to reach down that far. This would make photosynthesis impossible at such depths, and is one of the main arguments supporting the idea that Charnia was not a plant. Charnia does not seem to have been like known animal groups either however, which makes its position in current models of the tree of life uncertain. It seems that the fern-like appearance of Charnia is a result of a very simple method of growth where a latticework of tissues would grow in repeating patens, leading to the establishment of the uniform appearance. As far as feeding goes, most researchers agree that Charnia probably absorbed nutrients from the water around it, but the exact method of absorption is still currently a matter of debate amongst researchers.

Further Reading

- Pre-Cambrian fossils from Charnwood Forest. - Proceedings of the Yorkshire Geological Society 31(3):211-217. - Trevor D. Ford - 1958. - First occurrence of the Ediacaran fossil Charnia from the southern hemisphere. - Alcheringa 22 (3/4): 315–316. - C. Nedin & R. J. F. Jenkins - 1998. - Morphology and taphonomy of an Ediacaran frond: Charnia from the Avalon Peninsula of Newfoundland. - Geological Society, London, Special Publications 286 (1): 237–257. - M. Laflamme, G. M. Narbonne, C. Greentree & M. M. Anderson - 2007. - Charnia and sea pens are poles apart. - Journal of Geological Society 164 (1): 49. - J. B. Antcliffe, M. D. Brasier - 2007. - Charnia at 50: Developmental Models for Ediacaran Fronds. - Palaeontology 51 (1): 11–26. - J. B. Antcliffe, M. D. Brasier - 2008.