In Depth

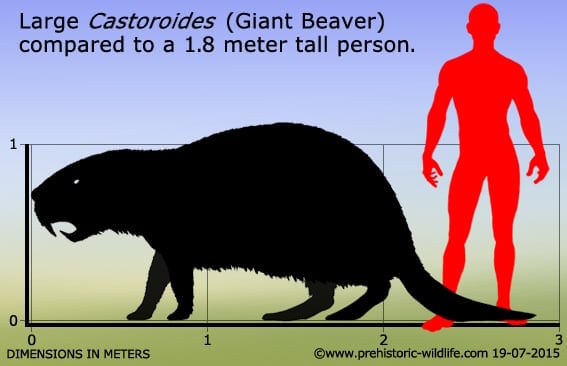

Castoroides is another example of how back in the Pleistocene animals were just bigger than they were today. Also known as the ‘giant beaver’, Castoroides is not just the largest beaver that we currently know about, but it is the largest rodent known to have ever lived on the North American continent. At the time of writing the only rodents known to have been bigger than Castoroides are Phoberomys and Josephoartigasia from South America.

Unfortunately no clear irrefutable evidence exists that proves that Castoroides built dams like modern beavers. Structures that might represent the prehistoric remains of such structures can also be explained away as other things such as flood deposits or naturally occurring accretions. Available evidence actually supports the theory that Castoroides did not build dams given that their incisors were not as well suited to cutting into wood as modern beavers have. However related genera do seem to have built lodges, which by association might indicate that Castoroides too also built lodges.

The extinction of Castoroides has for a long time been shrouded in mystery. While the disappearance of much of the North American Megafauna has been attributed to such factors as extreme glaciations, climate change, super volcanic eruptions, asteroid strikes, human hunting and combinations of all the above, Castoroides populations are actually known to have been in decline before this mass extinction took place. This has meant that the exact cause for the extinction of Castoroides has been unknown for almost two hundred years, but there may now be one idea which might go some way to explaining things. A 2011 paper by J. T. Faith detailed how nitrogen levels in the soil were declining at the time that Castoroides numbers were also declining.

Reduced levels of nitrogen in the soil cause a reduction in growth and nutritional quality of plants that require high nutrient levels. Herbivorous animals that rely upon such plants end up having to eat even greater amounts of them to maintain there population, but this results in even less nitrogen going back into the soil as leaf litter. This further reduces the crop of nitrogen rich plants the following year, which means even more had to be eaten, and again this made the problem much worse again the following year, and so on and on again until the ecosystem collapses and is unable to support the presence of such herbivorous. It Castoroides preferred eating plants that required high levels of nitrogen, then they would over successive seasons and generations slowly deplete available food plant supplies. Thus, unable to adapt to eating different plants, Castoroides may have ended up starving themselves into extinction.

Further Reading

– Two New Records of the Pleistocene Beaver, Castoroides ohioensis. – American Midland Naturalist 12 (12): 529–532. – William L. Engels – 1931. – Taxonomy of the giant Pleistocene beaver Castoroides from Florida. – Journal of Paleontology 43 (4): 1033–1041. – Robert A. Martin – 1969. – A giant beaver (Castoroides ohioensis Foster) fossil from New Brunswick, Canada. – Atlantic Geology 36 (1): 1–5. – R. F. Miller, C. R. Harrington & R. Welch – 2000. – Paleoecology of Northeast Indiana Wetland Harboring Remains of the Pleistocene Giant Beaver (Castoroides Ohioensis). – Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Science 110: 151. – Anthony L. Swinehart, Ronald L. Richards – 2001. – Additional records of the giant beaver, Castoroides, from the Mid-South: Alabama, Tennessee, and South Carolina. – Smithsonian Contribution to Paleobiology 93:65-71. – P. W. Parmalee & R. W. Graham – 2002. – Giant Beaver, Castoroides ohioensis, remains in Canada and an overlooked report from Ontario. – Canadian Field-Naturalist. 121 (3): 330–333. – C. R. Harington – 2007. - Late Pleistocene Climate Change, Nutrient Cycling, And The Megafaunal Extinctions In North America. - Quaternary Science Reviews 30: 1675–1680. - J. Tyler Faith - 2011.