In Depth

The name Carcharodontosaurus is derived from the Carcharodon genus of sharks, a group famous for including the great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias). This name was chosen because the teeth are sharp and serrated in a similar manner to the great white sharks, something that meant they could slice through the flesh of prey like sharp knives. These teeth were key to the hunting strategy of Carcharodontosaurus because when these teeth are arranged in a mouth the size that Carcharodontosaurus had, they would create a massive open wound. It is this wound that would effectively incapacitate the prey as blood loss would be so great that shock would quickly set in. This would cause the prey to become lethargic and disorientated allowing Carcharodontosaurus to easily close in and finish it off.

Although Carcharodontosaurus was named as its own genus by Ernst Stromer in 1931, it was actually known to science four years earlier, however when it was first described in 1927 it was described as a species of Megalosaurus. Although Megalosaurus is still one of the best known dinosaur names today, back in the early days of palaeontology it and many others where used as ‘wastebasket taxons’ where material was assigned upon the grounds of superficial similarity.

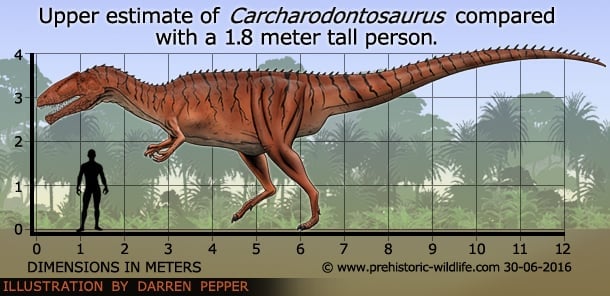

Even back then it was clear that Carcharodontosaurus was most probably slightly bigger than Tyrannosaurus, the dinosaur that was hailed as the biggest meat eater for the best part of a century. The main reason for the relative obscurity of Carcharodontosaurus throughout most of the twentieth century is that its only remains were destroyed in an allied bombing raid on Munich in world war two, an event that destroyed other fossils such as the first Spinosaurus remains, and the skull of the giant crocodile Stomatosuchus.

Interest began to rise in Carcharodontosaurus in the mid 1990s with the discovery of new Carcharodontosaurus material resulting in the naming of the second species C. iguidensis in 2007. Also another dinosaur named Sigilmassasaurus brevicollis was suggested as a junior synonym by Paul Sereno et al. in 1998 based upon strong similarities between it and Carcharodontosaurus. However a study in 2005 by Novas et al. has cast doubts upon this claim pointing out several differences between the associated Sigilmassasaurus material and that of Carcharodontosaurus. Even if Sigilmassasaurus is confirmed to be its own genus, the new fossil material of Carcharodontosaurus is enough to once again reconstruct this ancient predator as well as confirm its slightly larger size than Tyrannosaurus. The resurge of interest in Carcharodontosaurus can still be seen today with its almost mandatory inclusion in dinosaur books, appearances in video games and increasing appearances in dinosaur documentaries such as the BBC series Planet Dinosaur.

The discovery of new fossil material allowed for detailed studies into the brain of Carcharodontosaurus and how it may have lived and hunted. Carcharodontosaurus is often referenced as having a much smaller brain than Tyrannosaurus even though it is slightly larger, leading to the ungracious statement that it was much ‘stupider’. Such a statement is a grave misnomer however, as brain size itself is not as important as the development of individual parts of the brain such as senses, memory and reasoning. For example an animal with greatly enlarged sensory areas such as smell and vision would have a larger brain than another animal that was not as well adapted, but was still no more intelligent because the brain tissue for these areas do not make an animal better at thinking about problem solving, just better able to detect things.

The brain of Carcharodontosaurus exhibits features that hail back to the early archosaurs with similarities being seen in other reptiles such as crocodiles and turtles. The real interesting thing however is that the brain layout of Carcharodontosaurus is different to those of birds, and this reveals a growing evolutionary trend in dinosaurs that Carcharodontosaurus was not part of. The smaller brain size of Carcharodontosaurus was probably pre-determined by its archosaurian ancestry as many theropods of its ancestral line also have similar brain sizes meaning that while their bodies grew bigger, the brains stayed the same bringing a halt to further biological development. The coelurosaurian dinosaurs however, the lineage that would include Tyrannosaurus and the transitional line to birds developed their brains away from the older archosaurian form allowing for the potential of greater reasoning. This could be part of the reason why predators along the Carcharodontosaurid lineage would eventually disappear before the end of the Cretaceous when the new forms were more dominant.

Predators rely greatly upon their sense of smell for tracking prey over distances, although it is also probable that Carcharodontosaurus fed from carcasses of already dead dinosaurs when it was fortunate enough to find such an easy meal. When it came to killing its own prey Carcharodontosaurus seems to have been a primarily visually orientated predator (evidence by a large optic nerve), relying upon stereoscopic vision to provide depth perception to allow it to gauge distances between itself and prey.

Carcharodontosaurus is often falsely dubbed the ‘African T-rex’, something which has misled many people into thinking that they are the same. Really though the only similarities that they share are that they are both dinosaurs, and both theropods, and with this analogy you may as well call Carcharodontosaurus the ‘African Velociraptor’, it would be no more true or false than calling it the ‘African T-rex’. The difference between Carcharodontosaurus and Tyrannosaurus is immediately clear by looking at just the teeth. Carcharodontosaurus has laterally compressed (flattened) teeth that slice through flesh. Tyrannosaurus in contrast has round conical teeth for crushing bone. Include other differences such as size and shape of the skull and overall body proportions, and it is clear that the two are completely unrelated.

Carcharodontosaurus has been used to define its own group the Carcharodontosauridae which includes other giant theropods such as Giganotosaurus, Mapusaurus and Tyrannotitan. All of these predators have proportionately large skulls, large fenestra (skull openings), and serrated slicing teeth designed for cutting flesh rather than crunching bone. The Carcharodontosaurids seem to have evolved from earlier theropods like Allosaurus, and again this would display a different lineage from the tyrannosaurs which evolved from a coelurosaurian lineage. The carcharodontosaurids were quite common at one time during the Cretaceous, being represented by Acrocanthosaurus in North America, Neovenator in Western Europe and Shaochilong in China. However the carcharodontosaurids disappear from the fossil record before the end of the Cretaceous, being replaced by tyrannosaurids in the north and abelisaurids in the south.

Further Reading

Further reading – Wirbeltiere-Reste der Baharijestufe (unterestes Canoman). Ein Skelett-Rest von Carcharodontosaurus nov. gen – Abhandlungen der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Mathematisch-naturwissenschaftliche Abteilung, 9(Neue Folge): 1–23. – E. Stromer – 1931. – Predatory dinosaurs from the Sahara and the Late Cretaceous faunal differentiation – P. C. Sereno, D. B. Dutheil, M. Iarochene, H. C. E. Larsson, G. H. Lyon, P. M. Magwene, C. A. Sidor, D. J. Varricchio & J. A. Wilson – 1996. – A new method to calculate allometric length-mass relationships of dinosaurs. – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 21(1): 51–60. – F. Seebacher – 2001. – My theropod is bigger than yours…or not: estimating body size from skull length in theropods – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 27 (1): 108–115 – F. Therrien & D. M. Henderson – 2007. – A new species of Carcharodontosaurus (dinosauria: theropoda) from the Cenomanian of Niger and a revision of the genus. – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 27(4) – S. L. Brusatte & P. C. Sereno – 2007. – Balance and Strength—Estimating the Maximum Prey-Lifting Potential of the Large Predatory Dinosaur Carcharodontosaurus saharicus. – The Anatomical Record. 298 (8): 1367–1375. – D. M. Henderson & R. Nicholls – 2015.