In Depth

Although not as famous as some sauropods like Apatosaurus and Diplodocus, Camarasaurus actually appears to have been the most common judging by the large numbers of remains. Some Camarasaurus specimens are actually almost complete and the genus also has one of the largest numbers of sauropod skulls attributed (for those who haven’t realised the skull you see rotating at the top of every web page on this site is actually a replica of a Camarasaurus skull).

Camarasaurus was named in 1877 after Edward Drinker Cope bought the first fossils from Oramel W. Lucas. These remains were of an incomplete individual but were still valuable to Cope because the vertebrae had hollow chambers, something that gave rise to the name of ‘chambered lizard’. Back then these chambers were more a curiosity and were presumed to have been a weight saving feature that considerably reduced the weight of such a large dinosaur. Today however these chambers are interpreted as being air sacs that were actually part of the respiratory system of Camarasaurus. These features are seen in other sauropods, as well as similar systems in other dinosaur groups such as in the theropod Aerosteon, and would go to be called an avian-like respiratory system as birds also have similar air sacs inside their bodies. Back to Camarasaurus, the air sacs are thought to have allowed for a far more efficient flow of air down the long neck so that fresh air went down one network of sacs, while oxygen depleted air went up another. Thus a constant supply and exchange of breathable air was still taking place despite the distance of the lungs from the mouth and nostrils.

In 1925 Charles W. Gilmore retrieved a much better Camarasaurus specimen which was for lack of a better word complete. The main reason why it was so well preserved is because it was a younger and not fully grown individual, which meant that the body was probably buried before scavengers and environmental conditions could scatter and damage the skeleton. Unfortunately some took this specimen to be the literal size of all Camarasaurus, something which resulted in many Camarasaurus reconstructions being smaller than they really were in life.

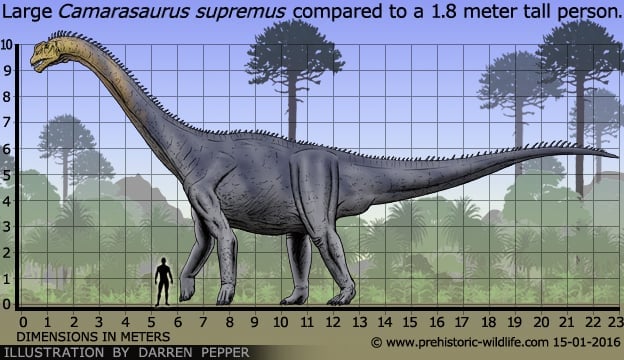

The largest number of Camarasaurus fossils is attributable to C. lentus, which is seen as having an average length of fifteen meters. The biggest species of Camarasaurus is the type C. supremus which grew up to twenty-three meters long. The shape of Camarasaurus’s body looked like it was something in between Apatosaurus and Brachiosaurus. The front limbs were shorter than the rear limbs, but the position and placement of the shoulder girdle meant that Camarasaurus still walked tall with a slight slope down the back towards the hind quarters. The neck appears to have been held up high so that the head and mouth were placed at a level where Camarasaurus could have comfortably browsed from the tree canopy and while the skull has many large fenestra it is remarkably robust and solid, possibly explaining the high standard of preservation that has come to be associated with Camarasaurus skulls. Overall this has led to Camarasaurus being declared a primitive (basal) macronarian, the grounp of high necked sauropods that included members such as Brachiosaurus, Giraffatitan and Lusotitan. Even though the skull has many large fenestra it is remarkably robust and solid, possibly explaining the high standard of preservation that has come to be associated with Camarasaurus skulls. The teeth are also very large and spatulate in form so that they could crop off vegetation from the coarser branches and growths. This is quite different from other sauropods such as Diplodocus which had weaker teeth, but a head position that saw them capable of easily feeding from softer low growing vegetation.

As with many genera that have multiple species assigned to the genus, not all of the species would have been active for the entire run of the genus. C. grandis was the first Camarasaurus species to appear and was eventually joined by C. lentus to which it coexisted until it disappeared after a few million years. C. lewesi also appears to have been present but not until the end of the genus. Paradoxically the first species of Camarasaurus named, C. supremus, appears to have actually been the last to live, and probably evolved from C. lentus. The Camarasaurus genus ending in the largest species is a trait that is commonly seen in other groups were the largest form is the last to appear, but also reveals a possible limit to the extent of that animal’s specialisation, as for further adaptation often ceases to take place.

Unlike some similar kinds of dinosaurs like Saltasaurus that have been found to lay eggs in nests, Camarasaurus eggs have been found in lines which suggest that Camarasaurus did not spend extensive amounts of time rearing young. They may have instead laid their eggs near undergrowth so that the newly hatched young could go straight to cover where they would have stayed until they grew large enough to venture into more open areas.

Some Camarasaurus bones and fossil sites have yielded valuable insights into their behaviour, biology and placement within the late Jurassic ecosystems of North America. One well documented case from Wyoming is the presence of two Camarasaurus adults and a single juvenile that appear to have been drowned while crossing a river that may have been in flood. The presence of individual Camarasaurus of different ages dying together has been taken as evidence of herding behaviour in Camarasaurus, with the three individuals suggesting that Camarasaurus lived in at least small groups, although the full extent of a herd’s size remains unknown. Similar bone beds are known for some ceratopsian dinosaurs like Centrosaurus and Styracosaurus from the Cretaceous, although in these deposits the individuals can number in hundreds.

A partial Camarasaurus grandis skeleton from Wyoming includes a humerus (upper ‘arm’ bone of the fore limb) that has been designated DMNH 2908. This humerus has an eighteen by twenty-five centimetre lesion on the bone that is composed of what seems to woven bone fibres. Analysis of this legion (by McWhinney, Carpenter, and Rothschild) suggests that the bone healed but with a growth that would have caused discomfort as the individuals muscles flexed around it. Many causes of this injury have been put forward, but the most likely seems to have been an avulsion, an injury where the muscle attachment has been torn free, removing some of the bone in the process. This could have been caused by a slip or a fall, or even repetitive strain, and may indicate that this individual Camarasaurus was living in area of uneven terrain that saw it going up and down inclines.

A Camarasaurus pelvis from Utah shows signs of damage that could have feasibly been caused by an Allosaurus, a dinosaur that was quite possibly the top predator of North America in the Jurassic. A problem here is that the fossil does not prove that the Camarasaurus was killed by an Allosaurus, just that an Allosaurus possibly fed upon the body after the time of death whatever the cause may be, including a dinosaur attack. A long held belief about sauropods was that they were near invulnerable because they were just too big to attacked by any of the predators. This idea however is no longer accepted without question, with some sauropods appearing to have armoured skin, and the fact that some predators, including Allosaurus, show signs of skeletal injuries that could have conceivably been caused by grappling with large and powerful prey. Strong fossil evidence also exists for Allosaurus attacking the armoured dinosaur Stegosaurus, and if Allosaurus could think to attack a herbivorous dinosaur that could have killed it with a strike from its spiked tail, then it does not seem entirely out of the question that an Allosaurus might have attempted to take down a Camarasaurus, especially if the Camarasaurus was sick or already injured.

Further Reading

– Notice of new dinosaurian reptiles from the Jurassic formation. – American Journal of Science and Arts 14:514-516. – O. C. Marsh – 1877. – Notice of new American Dinosauria. – The American Journal of Science and Arts, series 3 38:331-336. – O. C. Marsh – 1889. – The dorsal vertebrae of Camarasaurus Cope. – Bulletin of the AMNH ; v. 33, article 17. – Charles Craig Mook – 1914. – Notes of Camarasaurus Cope – Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences vol 24, iss 1 – Charles Craig Mook – 1914. – Camarasaurus, Amphicoelias, and other sauropods of Cope. – Bulletin of the Geological Society of America 30:379-388. – H. F. Osborn & C. C. Mook – 1921. – A nearly complete articulated skeleton of Camarasaurus, a saurischian dinosaur from the Dinosaur National Monument, Utah. – Memoirs of the Carnegie Museum 10(3):347-384. – C. W. Gilmmore – 1925. – Camarosaurus annae-a new American sauropod Dinosaur. – The American Naturalist, v. 84, p. 225-228. – T. U. H. Elinger – 1950. – A fourth new sauropod dinosaur from the Upper Jurassic of the Colorado Plateau and sauropod bipedalism. – The Great Basin Naturalist 48(2):121-145 – J. A. Jenson – 1988. – The Osteology of Camarasaurus lewisi (Jensen, 1988). – Brigham Young University, v. 41, p. 73-116. – J. S. McIntosh, W. E. Miller, K. L. Stadtman & D. G. Gillette – 1995. – Dental micro wear patterns of the sauropod dinosaurs Camarasaurus and Diplodocus: Evidence for resource partitioning in the late Jurassic of North America. – Historical Biology: An International Journal of Paleobiology. – col 13, iss13 – Anthony R. Fiorillo – 1998. – A New Nearly Complete Skeleton of Camarasaurus. – Bulletin of Gunma Museum of Natural History, n. 1, p. 1-87. – J. S. McIntosh, C. A. Miles, K. C. Cloward & J. R. Parker – 1996. – Evolution of High Tooth Replacement Rates in Sauropod Dinosaurs. – Plospme – Michael D. D’Emic, John A. Whitlock, Kathlyn M. Smith, Daniel C. Fisher & Jeffrey A. Wilson – 2013.