In Depth

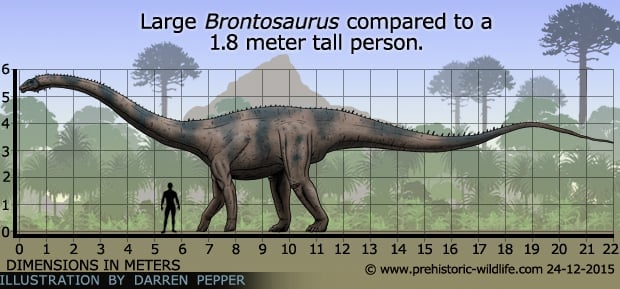

The turbulent history of Brontosaurus

For well over one hundred years there was a great question asked amongst dinosaur enthusiasts; is Brontosaurus actually Apatosaurus? Well this all began in a period of American paleontological history dubbed the ‘bone wars’, a fierce rivalry between two men named Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Charles Marsh. Both men named a great many prehistoric animals in an effort to outdo one another, and much of their work was rushed meaning that later palaeontologists had to revise their work in more detail.

During this time Marsh would name what would become two of the most famous dinosaurs of all time, Apatosaurus in 1877, and Brontosaurus in 1879. Not much else was really heard about these dinosaurs until 1903 when Elmer S. Riggs, a palaeontologist noted for his work on sauropod dinosaurs came to the conclusion that Brontosaurus was so similar to Apatosaurus that it should become a synonym. However, when the first skeleton of Apatosaurus was mounted in the American Museum of Natural History in 1905, it bore the name Brontosaurus as this had been picked out by Henry Fairfield Osborn (who in 1905 would also name Tyrannosaurus).

This one mounted skeleton is the reason why so much controversy would exist for this dinosaur for over a hundred years. As far as science was concerned, Brontosaurus did not exist except as a synonym to Apatosaurus, but the wider public only really heard about Brontosaurus, after all, Brontosaurus was the name on the display. From that point on Brontosaurus would get star billing in almost every popular science book about dinosaurs that was marketed towards children and the general public, as well as appear in later films featuring dinosaurs.

Aside from the naming confusion the mounted skeleton was not perfect. The skull was still unknown, so a man named Adam Hermann sculpted one based upon a dinosaur named Morosaurus, today listed as a synonym to Camarasaurus. The first clue to the true form of the skull came when the first Apatosaurus skull was found in 1909 by Earl Douglas, and it was immediately apparent that Apatosaurus had a similar skull to the sauropod dinosaur Diplodocus. By extension this would mean that the Brontosaurus display would need to have a new skull, and this was the opinion of Douglas and the then museum curator William H. Holland. However Henry Fairfield Osborn disagreed with this identification because the skull was found disarticulated from other remains. Later the mounted skeleton was left headless until 1934 when after Holland’s death, a cast of a Camarasaurus skull was added to it, once again giving it a box like had, something that would be repeatedly copied in all paleoart for Brontosaurus.

It was not until a 1975 study by John Stanton McIntosh and David Berman re-describing the skull and jaws of Apatosaurus and Diplodocus was published that things would really get moving for more accurate reconstructions. Specifically, many skulls of Apatosaurus had been known for a long time, they had just mistakenly been added into the Diplodocus genus on the basis of superficial similarities. McIntosh and Berman also noted that Holland was correct in his interpretation that the Brontosaurus mount had the wrong skull form. In October 1979, the first true Apatosaurus skull was mounted upon an Apatosaurus skeleton. In 1995 the original Brontosaurus mount from 1905 in the American Museum of Natural History finally got a skull revision to be like that of Apatosaurus, and was also now named as Apatosaurus excelsus, and not Brontosaurus excelsus. In 2011 the first Apatosaurus skull still articulated to the cervical (neck) vertebrae was described.

It took the best part of a century to reveal the true shape and form of Apatosaurus, and for most of this time the majority of palaeontologists agreed with the opinion of Elmer S, Riggs from 1903 that Brontosaurus should be a synonym to Apatosaurus. One notable exception however was Robert T. Bakker, who in 1998 argued that Apatosaurus and Brontosaurus are actually different enough to merit keeping Brontosaurus as a separate genus. It would not be until 2015 however that an extremely in-depth study conducted by Emanuel Tschopp, Octavio Mateus and Roger Benson would reveal one of the most ground breaking conclusions for over one hundred years. Using a statistical analysis of fossil specimens attributed to various different Apatosaurus species, they found that fossils once attributed as the Brontosaurus type species B. excelsus, could indeed be classed as different enough to resurrect it as a valid genus. They also concluded that the genera Elosaurus and Eobrontosaurus are actually synonymous with Brontosaurus.Brontosaurus the dinosaur

When first presented to the public Brontosaurus was a fairly generic sauropod dinosaur with four legs, long neck, long tail and a robust almost box-like head. Thanks to over one hundred years of study conducted upon Diplodocus and Apatosaurus, we now have a much better idea of what Brontosaurus would have been like. For a start the skull of Brontosaurus would have been quite elongated and not at all like Camarasaurus, which by the way is a very different kind of sauropod often referred to as a macronarian.

Brontosaurus is what is known as a member of the Diplodocidae due to its superficial similarity to Diplodocus. The Diplodocidae can be further broken down into the Diplodocinae for members closer to Diplodocus and the Apatosaurinae which is for members closer to Apatosaurus and are usually more robustly built than diplodocines. Because of its similarity to Apatosaurus, Brontosaurus can have its classification refined to that as an apatosaurine diplodocid sauropod dinosaur.

Brontosaurus used to be given a tail that was fairly short and generic, but we now know that Brontosaurus would have had a whip-like tail. Brontosaurus may have been able to crack this whip-tail to produce loud bangs. This may have been for signalling to others, used in dominance contests (the loudest sound belonging to the fittest/most powerful individual) to even deterring predatory dinosaurs such as Allosaurus, Torvosaurus or Ceratosaurus, or perhaps even a combination of all of the above.

Classic depictions of Brontosaurus usually show it wallowing around in swamps and lakes, often so submerged that only the head is above the water. This goes back to thinking going back to the nineteenth century that sauropods were so huge and heavy that they would need to use water buoyancy to take the load of their bodies off their legs and while they did this they would feed upon underwater plants while using their long necks to reach the surface of the water to breathe. This is not a bad idea, it’s just the wrong idea.

For a start the buoyancy is achieved by the water exerting pressure upon body. The water pressure exerted upon the lungs of an animal the size of Brontosaurus completely submerged in the water would be so great that breathing would be at best difficult, at worst near impossible, even if the head was out of the water. There is also the simple fact that the overwhelming majority of sauropods fossils come from what are dry inland areas such as plains and even sparse forests, some of which would have been several hundred feet above sea level back in the late Jurassic. Brontosaurus was certainly a dinosaur that preferred dryer inland areas, only approaching bodies of water to drink.

Brontosaurus is one of a great many sauropod genera known from the famous Morrison Formation of North America, though some have speculated that there may be ‘too many’ sauropod genera and some may represent synonyms to others. Indeed, just as many have wanted Brontosaurus to be separated from Apatosaurus, there are others who still credit it as synonymous with Apatosaurus. Aside from Diplodocus, Apatosaurus and Camarasaurus already mentioned, other sauropods that Brontosaurus may have come into contact with at some time or another include Brachiosaurus, Haplocanthosaurus, Supersaurus, Galeamopus, Barosaurus and the colossal Amphicoelias amongst others. Brontosaurus would have likely encountered other famous names such as Stegosaurus, Camptosaurus, Ornitholestes, Dryosaurus and Mymoorapelta, as well as larger predatory dinosaurs such as Allosaurus, Ceratosaurus, Torvosaurus and Saurophaganax.

Further Reading

– Notice of new Jurassic reptiles. – American Journal of Science and Arts 18:501-505. – O. C. Marsh – 1879. – Elosaurus parvus: a new genus and species of the Sauropoda. – Annals of Carnegie Museum 1:490-499. – O. A. Peterson & C. W. Gilmore – 1902. – Structure and Relationships of Opisthocoelian Dinosaurs. Part I, Apatosaurus Marsh. – Publications of the Field Columbian Museum Geographical Series 2 (4): 165–196. – Elmer S. Riggs – 1903. – Osteology of Apatosaurus, with special references to specimens in the Carnegie Museum. – Memoirs of the Carnegie Museum 11 (4): 1–136. – C. W. Gilmore – 1936. – Description of the Palate and Lower Jaw of the Sauropod Dinosaur Diplodocus (Reptilia: Saurischia) with Remarks on the Nature of the Skull of Apatosaurus. – Journal of Paleontology 49 (1): 187–199. – J. S. McIntoshh & D. S. Berman – 1975. – A new species of sauropod, Apatosaurus yahnahpin. – Wyoming Geological Association Field Conference 1994:123-134. – J. Filla & P. Redman – 1994. – Apatosaurus yahnahpin: a preliminary description of a new species of diplodocid dinosaur from the Late Jurassic Morrison Formation (Kimmeridgian-Portlandian) and Cloverly Formation (Aptian-Albian) of the western United States. – M�moires de la Soci�t� G�ologique de France (Nouvelle S�rie) 139 (Ecosyst�mes Continentaux du M�sozoique): 87-93. – J. A. Filla, P. D. Redman – 1994. – Dinosaur mid-life crisis: the Jurassic-Cretaceous transition in Wyoming and Colorado, by Robert T. Bakker. In, Lower and Middle Cretaceous Terrestrial Ecosystems. – New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 14: 67–77. – S.G. Lucas, J.I. Kirkland, & J.W. Estep (eds.). – 1998. - A specimen-level phylogenetic analysis and taxonomic revision of Diplodocidae (Dinosauria, Sauropoda). - PeerJ 3: e857. - Emanuel Tschopp, Octavio Mateus & Roger Benson - 2015. – P. M. Barrett, G. W. Storrs, M. T. Young & L. M. Witmer – 2011. - A specimen-level phylogenetic analysis and taxonomic revision of Diplodocidae (Dinosauria, Sauropoda). - PeerJ 3:e857. - E. Tschopp, O. Mateus & R. B. J. Benson - 2015