In Depth

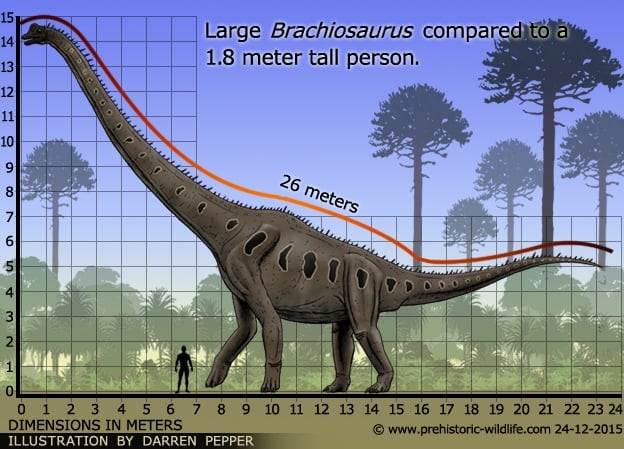

The sauropod dinosaur Brachiosaurus earned its name from the fact that the arms, or rather the fore legs as it was quadrupedal, are actually longer than the hind legs. The fact that these are longer offers Brachiosaurus a passive advantage in reaching up into the tree canopy to feed as the neck is always arched upwards as a result. Since the skeleton and vertebrae would be angled in such a way, Brachiosaurus would not need extra powerful muscles to lift the head and neck all the way up, reducing the effort to feed in such a specialised way. A further adaptation were the presence of air sacs located along the neck and trunk of Brachiosaurus. These connected to the lungs and had the effect of lowering the body density which in turn would reduce the total weight of the neck and trunk areas.

These adaptations meant that Brachiosaurus could easily live the life of a high browser feeding upon the tree canopy. Such specialisation also meant that Brachiosaurus would not have to compete with other herbivorous dinosaurs such as the low browsing Stegosaurus. Brachiosaurus could not chew its food as its jaws were only capable of opening and closing. Because of this it would use its spatulate (chisel like) teeth to crop the vegetation from the tops of trees.

Its possible that Brachiosaurus was gigantothermic meaning its massive body would hold onto body heat for longer than a smaller animal. This would give Brachiosaurus a higher metabolism than a ‘standard’ cold blooded or ‘ectothermic’ animal. However, the air sacs that would have been present inside of the body may also have provided extra cooling allowing Brachiosaurus to lower its body temperature and metabolism. This would also reduce the required calorie intake to keep its body going, reducing the required amount of time for feeding.

Fossils that were very similar to Brachiosaurus were recovered from the Tendaguru formation in Africa in 1914. This new species was given the name Brachiosaurus branchai, but upon further study of the bones, several morphological differences were discovered, and while the new specimen was similar to B. altithorax, it was still different enough to be considered separate. B. brancai has since been renamed Giraffatitan, with the type species changed to G. brancai.

It was once thought that Brachiosaurus had a skull like Giraffatitian, but when that was split off into its own group a possible key difference came to light. The crest forming bone that rises from the top of the skull of Giraffatitian, is much smaller in Brachiosaurus fossils. This crest was once thought to contain the nostrils but modern reconstruction places the nostrils further along the snout. This has led to speculation that this may have instead been a form of resonating chamber that could have been used to amplify the calls of Brachiosaurus.

Further Reading

– Brachiosaurus altithorax, the largest known dinosaur. – American Journal of Science, series 4 15:299-306. – Elmer S. Riggs – 1903. – Structure and relationships of opisthocoelian dinosaurs. Part II. The Brachiosauridae. – Geological Series (Field Columbian Museum) 2 (6): 229–247. – E. S. Riggs – 1904. – Die Sch�del der Sauropoden Brachiosaurus, Barosaurus und Dicraeosaurus aus den Tendaguru-Schichten Deutsch-Ostafrikas. – Palaeontographica (Suppl. 7) 2: 147-298. – W. Janensch – 1935/6. – New brachiosaur material from the Late Jurassic of Utah and Colorado. – The Great Basin Naturalist 47 (4): 592–608. – J. A. Jenson – 1987. – The brachiosaur giants of the Morrison and Tendaguru with a description of a new subgenus, Giraffatitan, and a comparison of the world’s largest dinosaurs. – Hunteria 2 (3). – G. S. Paul – 1988. – Preliminary description of a Brachiosaurus skull from Felch Quarry 1, Garden Park, Colorado, by K. Carpenter & V. Tidwell. In The Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation: An Interdisciplinary Study. Modern Geology, 23:1-4, K. Carpenter, D. Chure & J. Kirkland (eds.). – Biostratigraphy of dinosaurs in the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation of the Western Interior, USA, by C. E. Turner & F. Peterson. In Vertebrate Paleontology in Utah. Miscellaneous Publication 99-1. Salt Lake City, Utah: Utah Geological Survey. pp. 77–114. (David G. Gillete (ed.)). – 1999. – Paleoecological analysis of the vertebrate fauna of the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic), Rocky Mountain region, U.S.A. – New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 23. Albuquerque, New Mexico: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. – J. R. Foster – 2003. – First occurrence of Brachiosaurus (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) from the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation of Oklahoma. – PaleoBios 24 (2): 12–21. – M. F. Bonnan & M. J. Wedel – 2004. – Brachiosaurus altithorax. – Jurassic West: The Dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation and Their World. Indiana University Press. pp. 205–208. – J. Foster – 2007. – In vitro digestibility of fern and gymnosperm foliage: implications for sauropod feeding ecology and diet selection. – Proceedings of the Royal Society B 275: 1015–1021. – J. Hummel, C. T. Gee, K.-H. S�dekum, P. M. Sander, G. Nogge & M. Clauss – 2008. – A re-evaluation of Brachiosaurus altithorax Riggs 1903 (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) and its generic separation from Giraffatitan brancai (Janensh 1914). – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 29 (3): 787–806. – M. P. Taylor – 2009. – Correction: A re-evaluation of Brachiosaurus altithorax Riggs 1903 (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) and its generic separation from Giraffatitan brancai (Janensch 1914). – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 31 (3): 727. – M. P. Taylor – 2011.- Redescription of Brachiosaurid Sauropod Dinosaur Material From the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation, Colorado, USA. – Anatomical Record. 303 (4): 732–758. – Michael D D’Emic & Matthew T Carrano – 2020.