In Depth

Although named in 1892, no one had any idea of the true identity of Anomalocaris until towards the end of the twentieth century.

The first specimen was originally thought to be a shrimp, but with hindsight we now know this specimen to only represent one of the frontal grasping appendages.

The second clue was a mouth, although this ended up being classified under the Peytoia genus of jellyfish.

Not only does the fossilised mouth of Anomalocaris look very much like a jellyfish, it is also often referred to as a pineapple ring due to its resemblance to a sliced pineapple.

When discovered the body of Anomalocaris was thought to be a sponge of the Laggania genus.

Then fossils started to occur where all of the parts were together, although the usual identification would be along the lines of a jellyfish preserved against a sponge, not a mouth connected to a body.

Eventually however they were pieced together and the realisation came that these ‘composites’ were actually representations of a single creature.

Even though the creature was nothing like it was first assumed to be, the name Anomalocaris was still valid because it was the first name assigned to a previously unidentified specimen, the initial appendage.

Peytoia is now also a distinct genus of related anomolocarid.

Anomalocaris is often termed a proto-arthropod, meaning that while it was of the same lineage to arthropods, it may have been of a slightly different evolutionary line as arthropods as we known them today.

Early on Anomalocaris was often depicted with a hard chitinous body like say a crab shell, but today it seems that this might not be correct.

The hardest parts seem to have been the forward appendages and the mouth, hence the reason why fossils of these parts are fairly common in relation to the preservation of the other parts.

The main body itself seems to have been softer in relation to these parts, with lobes extending from the sides of the main body.

These lobes grew in such a way so that even though they were separate, each lobe would be so large that it would grow under the one to the rear of it, creating a more ‘complete’ surface to push against the water.

Modelling of undulating patterns that these lobes would have moved in has revealed that this form of locomotion would have offered very stable and efficient swimming with little need to move the main body.

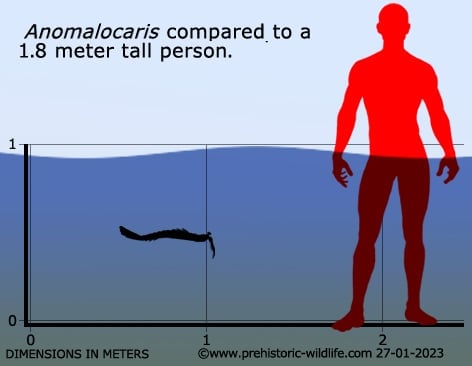

Most of the known creatures of the Cambrian seas were very small, but Anomalocaris was a clear exception to this rule.

Anomalocaris Fossils usually represent individuals between sixty and one hundred centimetres in length.

When depicted in popular culture and documentaries Anomalocaris is often depicted as an apex predator that chases after trilobites before ripping them in two and crunching up the shells.

However, some people have questioned the classical view of Anomalocaris crushing and eating hard shelled arthropods because computer models have suggested that Anomalocaris could not close its mouth completely.

Some also point to the lack of hard prey shells that have not been found in association with Anomalocaris specimens.

While the appendages at the front could have been used for tearing, the spines that are underneath might have conceivably been used for filtering sediment and trapping smaller prey.

Once prey was found, the appendage would curl round to pass the food into its mouth.

Such a feeding method would not require the mouth to close fully, just enough to make contact with the appendage.

It is also worth noting that the tooth like prongs of the mouth also extend inwards towards the gullet, perhaps to cover the length of the inserted appendage, although this feature only reveals the feeding method, not the diet.

Before you decide whether Anomalocaris was some kind of filter feeder instead of an active apex predator, you have to take into account the nutritional value of a trilobites shell, as well as the fact that trilobites would have been soft on the inside.

It’s just as likely that this sucking mouth could have been used to suck the soft trilobite flesh from their shells, with both feeding lifestyles being possible.

Anomalocris is now the type genus of the Anomalocarida, a whole group of creatures similar to Anomalacris.

Further Reading

- Anomalocaris, the largest known Cambrian arthropod. – Palaeontology vol 22, part 3, pp631-66. – D. E. G. Briggs – 1979.

- – The Occurrence of the Giant Arthropod Anomalocaris in the Lower Cambrian of Southern California, and the Overall Distribution of the Genus. – Journal of Paleontology 56 (5): 1112–8. – D. E. G. Briggs & J. D. Mount – 1982.

- – Exceptionally preserved nontrilobite arthropods and Anomalocaris from the Middle Cambrian of Utah. – University of Kansas Paleontological Contributions (111). – D. E. G. Briggs & R. A. Robison – 1984.

- – The largest Cambrian animal, Anomalocaris, Burgess Shale, British Columbia. – Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 309 (1141): 569–609. – H. B. Whittington & D. E. G. Briggs – 1985.

- – Anomalocaris and other large animals in the Lower Cambrian Chengjiang fauna of southwest China. – Geologiska Föreningens i Stockholm Forhandlingar 117:163-183. – X.-G. Hou, J. Bergström & P. Ahlberg – 1995.

- – Anomalocaris predation on nonmineralized and mineralized trilobites. – Geology 27 (11). – C. Nedin – 1999.

- – Theoretical study on the body form and swimming pattern of Anomalocaris based on hydrodynamic simulation. – Journal of Theoretical Biology 238 (1): 11–7. – Yoshiyuki Usami – 2006.

- – Acute vision in the giant Cambrian predator Anomalocaris and the origin of compound eyes. – Nature 480 (7376). – John R. Paterson, Diego C. García-Bellido, Michael S. Y. Lee, Glenn A. Brock, James B. Jago & Gregory D. Edgecombe – 2011.

- – The oral cone of Anomalocaris is not a classic ‘Peytoia‘. – Naturwissenschaften. – A. Daley & J. Bergström – 2012.

- – New anatomical information on Anomalocaris from the Cambrian Emu Bay Shale of South Australia and a reassessment of its inferred predatory habits. – Palaeontology. – A. C. Daley, J. R. Paterson, G. D. Edgecombe, D. C. Garcia-Bellido & J. B. Jago (Philip Donoghue, ed.). – 2013.

- – Arthropod appendages from the Weeks Formation Konservat-Lagerstätte: new occurrences of anomalocaridids in the Cambrian of Utah, USA. – Bulletin of Geosciences: 269–282. R. Lerosey-Aubril, T. A. Hegna, L. E. babcock, E. Bonino & C. Kier – 2014.

- – On the Hydrodynamics of Anomalocaris Tail Fins. – Integrative and Comparative Biology. 58 (4): 703–711. – K. A. Sheppard, D. E. Rival & J.B. caron – 2018.

- – Exceptional multifunctionality in the feeding apparatus of a mid-Cambrian radiodont. – Paleobiology. 47 (4): 704–724.. – J. Moysiuk & J. B. Caron – 2021.