In Depth

Along with Tyrannosaurus, Allosaurus is probably the most often represented large theropod dinosaur in popular culture. This is because it was one of the earliest discovered large predators and is known from more remains than any other large predatory dinosaur. One myth about Allosaurus that does need to be dispelled is that it was the ancestor of Tyrannosaurus. Although both share a similar morphology and Allosaurus is much older, the tyrannosaurids are thought to have evolved from the coelurosaurid group independent of Allosaurus. This means that as the tyrannosaurids evolved, they replaced dinosaurs like Allosaurus as the dominant theropods of North America.Many names but just one dinosaur?

The discovery of Allosaurus was a result of the ‘bone wars’, a time of large scale fossil discoveries across North America. Unfortunately due to the nature of what was going on during the bone wars, different sets of Allosaurus were named under a few different species. This has resulted in other palaeontologists having to re-evaluate the original fossil material and put the remains in their correct places, resulting in the reduction of species names and the synonymization of other dinosaurs into Allosaurus.

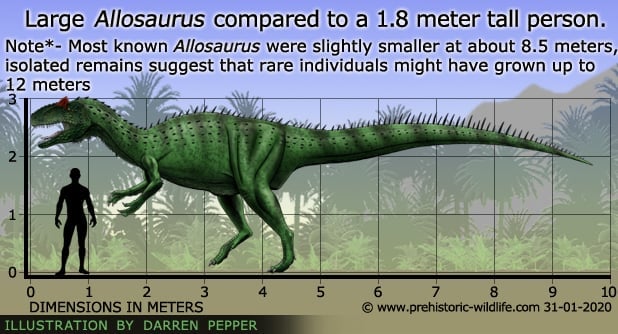

Although existing synonyms for Allosaurus include Antrodemus, Creosaurus and Labrosaurus, two more dinosaurs named Epanterias and Saurophaganax may also prove to be additional examples of Allosaurus. Both Epanterias and Saurophaganax are only known from partial remains, yet both are significantly larger than Allosaurus with size estimates approaching (and occasionally exceeding) eleven metres long. While some researchers already consider them to be larger individuals of Allosaurus, others are more inclined to wait upon new material and further study.

The Allosaurus genus has had a lot of additional species attributed to it, and the list of confirmed species has been changing sporadically throughout most of the history of the genus. A. fragilis, the type species of Allosaurus has and always will be valid. A. europaeus and A. jimmadseni are often also credited as valid. Further species such as A. amplexus, A. atrox, A. maximus and A. tendagurensis are more controversial.

Further study of Allosaurus is undoubtedly needed to resolve the species naming issues, but part of the problem is the holotype specimen itself. When Othniel Charles Marsh first described Allosaurus in 1877 he did not have the complete dinosaur, although somewhat ironically his rival Edward Drinker Cope acquired a particularly well preserved specimen two years later, but failed to realise the significance as the raw material remained in storage while he worked on other fossils. The holotype specimen itself was composed of a right humerus, a few vertebrae, teeth, toe bone and a fragment of a rib. As such subsequent discoveries were studied against this incomplete material, but not always against other Allosaurus discoveries, resulting in numerous ‘new’ species that under modern study do not appear all that different. This is why many Palaeontologists have called for a neotype specimen to be established from one of the more complete later discoveries, so that new and existing findings can be measured against much more accurate data.Allosaurus Morphology

Allosaurus had the typical theropod morphology of a bipedal stance on two large legs and a long tail held out to counter-balance the head of an S curved neck. The most distinctive feature of Allosaurus are the small horns above its eyes which are special growths of the lacrimal bone of the skull. Theories as to their purpose include potential weapons or sun shades to prevent glare in the eyes, to the more widely accepted species recognition of its own kind, and possibly display for attracting a mate.

The placement of the eyes in the skull shows that while Allosaurus did have binocular vision, it was limited to twenty degrees. This means that Allosaurus would need to make sure that its prey stayed directly in front of it, because if its prey turned sharply, it could quite easily break this cone of vision. Although Allosaurus would still see the prey, it would only be able to use one eye and as such would not have depth perception which could result in a missed strike. Although it seems easy enough to point out that Allosaurus would just have to turn its head to regain depth perception, a successful strike requires split second timing with only the smallest margin of error. A loss of depth perception for only a fraction of a second may have been enough for a prey item to avoid being bitten.

CT scans of Allosaurus skulls have revealed a few interesting glimpses into the life of the living animal. The Brain is similar to those found in crocodiles, and Allosaurus had very large olfactory bulbs, but had an underdeveloped area for assessing them. It could be that Allosaurus relied upon only recognising a few smells, such as prey animals, carrion, or even others of its own kind. The inner ear seems best suited to low frequency sounds, and analysis of the vestibular system, the part that controls balance, shows that the head was usually held horizontally level.

The arms are very robust when compared to later large theropods, and the hands end with three digits that have large claws. The retained development of the arms suggests that they played a key role in the lifestyle of Allosaurus, but the actual method of use remains open to strong debate among palaeontologists.

The overall morphology of Allosaurus is dependent upon the age of the individual, with juvenile specimens consistently showing proportionately longer legs than adults. This suggests that juvenile Allosaurus were very quick, perhaps among the fastest of the dinosaurs of that time and location. This would make a whole lot of sense as when small, the only prey items available to juvenile Allosaurus were smaller and quicker animals.

As Allosaurus grew older and increased in size is would need more sustenance that could only be provided by larger dinosaurs. Since these are generally slower and heavier, Allosaurus morphed with age to have shorter and more robust legs to better deal with the stresses of tackling them. For such prey items, high speed would be an unnecessary luxury, and longer lighter legs would have only been more susceptible to injury.

Interestingly, although Allosaurus is not directly related to them, this changing morphology of longer legged and faster juveniles can also be seen in tyrannosaurids such as Albertosaurus. This could possibly serve as a case on convergent evolution in larger theropods, although the genetic markers for such growth may herald from further back in dinosaur evolution.Feeding strategy

Although it seems to be a foregone conclusion that Allosaurus was a predatory animal, it like Tyrannosaurus has been accused of being just a scavenger. This primarily comes from the head and dentition, as although the head is very strongly built, the bite force of Allosaurus was very weak for a large theropod with some studies suggesting that it was even less than a modern day big cat like a leopard.

For this reason you have to look at other areas of the body, particularly the arms that were proportionately larger than much later large theropods like Tyrannosaurus. There is also a large number of injuries to the arms including tendon avulsions, which is where the tendon that connects the muscle to the bone is torn free, sometimes with part of the bone still attached. Now a carcass doesn’t struggle when a carnivore scavenges it, so these kinds of injuries must be caused by conflict with another dinosaur, although conversely it’s fair to say that they may have been caused in a struggle with another Allosaurus.

Even if the other dinosaur was another Allosaurus, it does still show that Allosaurus could be extremely aggressive when it needed to be. Had the arms come into use when hunting, then Allosaurus may have gripped hold of an animal as it positioned its mouth to strike at a soft spot like the throat. Such a target wouldn’t necessarily require a lot of bite force, just enough to do some damage to the veins or maybe close off the wind pipe. This would mean that its mode of attack was not particularly refined because whereas Tyrannosaurus could easily use its tremendous bite force to kill with a bite to the back of a neck, and Deinonychus could stab a jugular vein with its sickle claw, Allosaurus had little choice but to get physical with its prey.

While the above is a very generalist approach to attacking and dispatching prey, there is room for more specialised feeding. The jaws of Allosaurus could open extremely wide, in part due to the weaker bite muscles not resisting its opening so much. By opening its jaws wide, Allosaurus could in theory use its jaws as a kind of rasp to strip off thin strips of surface flesh from its prey. Several bites like this would have the effective of subjecting its prey to tremendous blood loss, possibly to the extent of causing it to collapse. This would go some way to explaining the solid skull construction and quite small teeth. It could also support a flesh grazing theory where Allosaurus could attack and feed from a large sauropod without actually killing it.

Regardless of the actual strategy, good evidence for Allosaurus being an active predator comes from a fossilised vertebra that shows an impact inflicted by a thagomizer tail spike from a Stegosaurus. As a Herbivore, Stegosaurus would have had no reason to lash out against an already dead Allosaurus as only a living animal could have posed a threat. Another Stegosaurus fossil shows a bite mark to one of its neck plates that seems to have been inflicted from an Allosaurus. These fossil remains indicate that Stegosaurus may have formed an important albeit heavily armoured part of the Allosaurus diet. Regardless of how active a hunter Allosaurus was, it would almost certainly not pass up the chance of a free meal when one was presented. There are also significant fossil finds that also indicate that Allosaurus regularly scavenged the carcasses of dinosaurs, possibly even members of its own species.Significant discoveries

Allosaurus had a broad expanse that included much of the prehistoric USA. However discoveries that lie further afield may actually represent similar but different species of dinosaur. The only really accepted remains of a non-American Allosaurus are found in Portugal and are referred to as A. europaeus. Another common non-American species that is often cited as Allosaurus is A. tendagurensis from Tanzania, although this material is fragmentary and thought by many to represent another kind of Theropod.

Part of the confusion for potential remains comes from the fact that Allosaurus had a successful body plan that was seen in a large number of other Jurassic Theropods. Afrovenator, a carnivorous dinosaur from North Africa is very similar to Allosaurus except for its slightly longer forearms. Other dinosaurs such as Fukuiraptor from Japan and Australovenator from Australia are so similar that they frequently have comparisons drawn between them and Allosaurus.

Most of the major discoveries pertaining to Allosaurus have been made in the USA, and more specifically the Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry in Utah. This is but part of the large Morrison Formation that has yielded many of the most important dinosaur discoveries, but at this quarry is a huge bone bed of dinosaurs, of which at least over forty Allosaurus individuals have been identified with many more likely awaiting discovery.

A very interesting fact about the Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry is that the predators outnumber the herbivores by a ratio of about 3:1. Although this has raised the notion of pack hunting in dinosaurs such as Allosaurus, a study of the site geology reveals deposits of mudstone, formed by a river system that created mud flats. It is thought that herbivores became trapped in the mud, which in turn attracted predatory dinosaurs intent upon feeding on the trapped dinosaurs only to find themselves trapped.

This means that the Cleveland-Lloyd site most likely represents an ancient predator trap, one that has managed to preserve, among others, several juvenile specimens helping to reveal the growth of Allosaurus. The large number of remains, although not indicative of pack hunting, may be interpreted that scavenging formed an important part of Allosaurus feeding strategy. This is evidenced by the fact that at least forty-four Allosaurus individuals are known, where as there are only about seven other sets of remains of carnivorous dinosaurs, and these are all different species such as Ceratosaurus and Stokesosaurus.

Amongst the vast Allosaurus remains at the Cleveland-Lloyd quarry one bone in particular proved to be of very special interest. This was a tibia (shin bone) that belonged to what must have been a female Allosaurus as it shows the presence of medullary tissue. Medullary tissue is found in the females of modern birds and is used as a calcium reserve for egg shell production during ovulation. Another insight is that the individual is estimated to have only been ten years of age, meaning that she was no way near fully grown when she reached reproductive maturity. The discovery of medullary tissue is not unique to Allosaurus with medullary tissue also being found in Tyrannosaurus and the herbivore Tenontosaurus, discoveries that further establish the link between dinosaurs and modern birds.

In 1991 an Allosaurus that would be named ‘Big Al’ was discovered in Wyoming. With ninety-five per cent of the individual recovered it was at the time the best preserved Allosaurus, but even more significantly Big Al showed signs of a startling number of injuries and infections. These include damage to the ribs, toe bones and vertebra, not just breaks but also subsequent bone infection known as Osteomyelitis. This is where microorganisms infect a bone that has been damaged by some kind of trauma that has resulted in a break, which in turn are attacked by the body’s immune system. The results can include blood vessels in the bone becoming blocked by pus, in turn resulting in bone tissue dying (a process called necrosis) and the body then attempting to grow new bone around the dead tissue.

The results of the infection are misshapen bones that can as in the case of the toe bones impair mobility reducing the chance to effectively hunt other dinosaurs. This could explain why Big Al was a sub adult, and estimated to have only been eighty-seven per cent fully grown at the time of death. A possible life scenario for Big Al formed the basis for the television documentary special The Ballad of Big Al.Inter species interaction

Conflicts among Allosaurus individuals were almost certainly common as they often are among predators today. As in other predators these conflicts would have usually been for the rights to feed at a carcass, or mating rights, perhaps even by a potential mate that was not interested in the attentions of the wrong individual. These encounters can be seen in the injuries that appear to have been inflicted by other Allosaurus such as teeth marks to jaws.

Because Allosaurus was probably the apex predator of its time, and evidence shows that it did not shy away from creatures equally as big as itself. However many of the potential prey items were much bigger, and these were the massive sauropods that roamed the Jurassic of North America. When juvenile, a sauropod would have been easy pickings for an adult Allosaurus, but it’s quite inconceivable that even an adult Allosaurus would have been able to take down a fully grown sauropod like Brachiosaurus. This has led to the suggestion of pack hunting, with multiple Allosaurus individuals attacking a single herbivore that otherwise would have been too big to attack. The idea of pack hunting is a controversial one as many people will say that dinosaurs didn’t hunt in packs because you don’t see lizards teaming up to take down larger prey today. This of course depends on how much dinosaurs were like lizards, not just in biology but behaviour as well.

A possible ‘middle ground’ for the idea that several Allosaurus could gather to attack a large sauropod is what’s termed ‘mobbing behaviour’. This is where rather than working to a coherent plan, several individuals relentlessly attack a creature that has become separated from the group and wear it down by attrition. When the animal can take no more it collapses and the predators move in to it. This behaviour has been seen in some birds, and since they are considered to be direct descendants of the dinosaurs, there behaviour patterns are more easily accepted when transferred to dinosaurs.

One study that can be mentioned is the reaction of African predators to the sounds of animals in distress. This study is often cited as support for potential pack hunting in the sabre toothed cat Smilodon, and was centred on playing the recordings of prey animals that were in distress like they would be when stuck in the mud. The quick revelation for this study found that predominantly social and pack hunting predators approached the sounds, while the solitary predators mostly stayed away. It was theorised that this occurrence came about from the fact the solitary, and usually smaller predators knew that the animals in distress would be attracting larger and more numerous predators to that area, and as such stayed away in order to avoid becoming food for the other predators themselves.

Remember that at the Cleveland-Lloyd Quarry, Allosaurus remains vastly outnumber the remains of other predators. Also, study of the geology reveals strong evidence for an ancient predator trap that would attract predators looking for an easy meal. Now it would be very careless to claim that this is absolute proof of pack hunting in Allosaurus, but what should be remembered is that this study is less about actual animal biology and more about the behaviour and interaction between known solitary and pack hunting animals. It should also be remembered that big mammalian predators are the only animals that currently fill the ecological niches that large predatory dinosaurs once did.

It may well be that we will never be able to say the extent if indeed any social interaction that Allosaurus individuals had with one another, as proposed theories are always down to the individual interpretation of fossil material. It is only when the interpretations begin to fit in with one another across multiple examples of evidence can we begin to say things with even a small degree of certainty.

Further Reading

– Notice of new dinosaurian reptiles from the Jurassic formation. – American Journal of Science and Arts. 14 (84): 514–516. – Othniel Charles Marsh – 1877. – Notice of new dinosaurian reptiles. – American Journal of Science and Arts. 15 (87): 241–244. – Othniel Charles Marsh – 1878. – A new opisthocoelous dinosaur. – American Naturalist. 12 (6): 406–408. – Edward Drinker Cope – 1878. – American Jurassic dinosaurs. – Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science. 6: 42–46. – Samuel Wendell Williston – 1878. – Principal characters of American Jurassic dinosaurs. Part II. – American Journal of Science. Series 3. 17 (97): 86–92. – Othniel Charles Marsh – 1879. – The dinosaurian genus Creosaurus, Marsh. – American Journal of Science. Series 4. 11 (62): 111–114. – Samuel Wendell Williston – 1901. – Osteology of the carnivorous dinosauria in the United States National Museum, with special reference to the genera Antrodemus (Allosaurus) and Ceratosaurus. – Bulletin of the United States National Museum. 110 (110). – Charles W. Gilmore – 1920. – Allosaurus fragilis: A Revised Osteology. Utah Geological Survey Bulletin 109 (2nd ed.). – Salt Lake City, Utah Geological Survey – .James H. Madsen – 1993. – A reassessment of the gigantic theropod Saurophagus maximus from the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic) of Oklahoma, USA. – Daniel J. Chure – 1995. – A discriminant analysis of Allosaurus population using quarries as the operational units. – Museum of Northern Arizona Bulletin. 60. – David K. Smith – 1996. – On the presence of furculae in some non-maniraptoran theropods. – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 16 (3). – Daniel J. Chure & James Madsen – 1996. – The discovery of a nearly complete Allosaurus from the Jurassic Morrison Formation, eastern Bighorn Basin, Wyoming. – Brent Breithaupt – 1996. – A morphometric analysis of Allosaurus. – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 18. – David K. Smith – 1998. – Skull and tooth morphology as indicators of niche partitioning in sympatric Morrison Formation theropods. – Gaia. 15: 219–266. – Donald M. Henderson – 1998. – Patterns of size-related variation within Allosaurus. – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 19 (2). – David K. Smith – 1999. – On the presence of Allosaurus fragilis (Theropoda: Carnosauria) in the Upper Jurassic of Portugal: First evidence of an intercontinental dinosaur species. – Journal of the Geological Society. 156 (3). – B. P. P�rez-Moreno, D. J. Chure, C. Pires, C. Marques Da Silva, V. Dos Santos, P. Dantas, L. Povoas, M. Cachao & J. L. Sanz – 1999. – Allosaurus, crocodiles, and birds: Evolutionary clues from spiral computed tomography of an endocast. – The Anatomical Record. 257 (5). – Scott W. Rodgers – 1999. -Theropod forelimb design and evolution. – Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 128 (2): 149–187. – Kevin M. Middleton. – 2000. – Observations on the morphology and pathology of the gastral basket of Allosaurus, based on a new specimen from Dinosaur National Monument. – Oryctos. 3. – Daniel J. Chure – 2000. – Forelimb biomechanics of nonavian theropod dinosaurs in predation. – Senckenbergiana Lethaea. 82 (1): 59–76.Kenneth Carpenter – 2002. – Multiple injury and infection in a sub-adult theropod dinosaur (Allosaurus fragilis) with comparisons to allosaur pathology in the Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry Collection. – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 22 (1). – Rebecca R. Hanna – 2002. – Paleoecological Analysis of the Vertebrate Fauna of the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic), Rocky Mountain Region, U.S.A. – New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 23. – John R. Foster – 2003. – Morphology, taxonomy, and stratigraphy of Allosaurus from the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 23 (3). – Mark A. Loewen, Scott D. Sampson, Matthew T. Carrano & Daniel J. Chure – 2003. – Sizing the Jurassic theropod dinosaur Allosaurus: Assessing growth strategy and evolution of ontogenetic scaling of limbs. – Journal of Morphology. 267 (3). – Paul J. Bybee, A. H. Lee & E. T. Lamm – 2006. – The large theropod fauna of the Lourinha Formation (Portugal) and its similarity to that of the Morrison Formation, with a description of a new species of Allosaurus. – Oct�vio Mateus, Aart Walen & Miguel Telles Antunes – 2006. – Hindlimb allometry in the Late Jurassic theropod dinosaur Allosaurus, with comments on its abundance and distribution, by John R. Foster & Daniel J. Chure. In Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 36. – John. R. Foster & Spencer G. Lucas (eds). – Jurassic West: the Dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation and Their World. – Bloomington, Indiana:Indiana University Press. – John Foster – 2007. – The case of “Big Al” the Allosaurus: a study in paleodetective partnerships. – Brent H. Breithaupt – 2007. – Nuevos restos de Allosaurus fragilis (Theropoda: Carnosauria) del yacimiento de Andr�s (Jur�sico Superior; centro-oeste de Portugal) [New remains of Allosaurus fragilis (Theropoda: Carnosauria) of the Andr�s deposit (Upper Jurassic; central-west Portugal)]. Cantera Paleontol�gica. – Elisabete Malafaia, Pedro Dantes, Francisco Ortega & Fernando Escaso – 2007. – How big was ‘Big Al’? Quantifying the effect of soft tissue and osteological unknowns on mass predictions for Allosaurus (Dinosauria:Theropoda). – Palaeontologia Electronica. 12 (3). – Karl T. Bates, Peter L. Falkingham, Brent H. Breithaupt, David Hodgetts, William I. Sellers & Philip L. Manning – 2009. – Allosaurus Marsh, 1877 (Dinosauria, Theropoda): proposed conservation of usage by designation of a neotype for its type species Allosaurus fragilis Marsh, 1877. – Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature. 67 (1). – Gregory S. Paul & Kenneth Carpenter – 2010. – Variation in a population of Theropoda (Dinosauria): Allosaurus from the Cleveland-Lloyd Quarry (Upper Jurassic), Utah, USA. – Paleontological Research. 14 (4).Kenneth Carpenter – 2010. – Allosaurus fed more like a falcon than a crocodile: Engineering, anatomy work reveals differences in dinosaur feeding styles. – Ohio University – 2013. – Osteology of a large allosauroid theropod from the Upper Jurassic (Tithonian) Morrison Formation of Colorado, USA. – Volumina Jurassica. 12 (2). – Sebastian G. Dalman – 2014. – New insights into the lifestyle of Allosaurus (Dinosauria: Theropoda) based on another specimen with multiple pathologies. – PeerJ PrePrints. 3. – C. Foth, S. Evers, B. Pabst, O. Mateus, A. Flisch, M. Patthey & O. W. M. Rauhut – 2015. – Cranial anatomy of Allosaurus jimmadseni, a new species from the lower part of the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic) of Western North America. – PeerJ. 8: e7803. – D. J. Chure & M. A. Loewen. – 2020. – Notes on the cheek region of the Late Jurassic theropod dinosaur Allosaurus. – PeerJ. 8: e8493. – Serjoscha W. Evers, Christian Foth, & Oliver W.M. Rauhut – 2020. – High frequencies of theropod bite marks provide evidence for feeding, scavenging, and possible cannibalism in a stressed Late Jurassic ecosystem. – PLOS ONE. 15 (5): e0233115. – Stephanie K. Drumheller, Julia B. McHugh, Miriam Kane, Anja Riedel & Domenic C. D’Amore – 2020.