In Depth

Acrocanthosaurus immediately sticks out from other large theropods with its high dorsal spines than run from the neck to the tip of the tail. There have been many artistic representations for this structure from the spines standing proud from the body, to supporting a flap of skin. Modern thinking however comes from the examination of the lower spines that have attachments for muscles. This has led to the suggestion that the spines supported a hump of tissue that ran down the length of Acrocanthosaurus.

The purpose of the hump of Acrocanthosaurus has been subject to a lot of speculation. Some have said that it would provide a larger surface area than Acrocanthosaurus would have had without it, helping with temperature exchange and reducing negative effects of gigantothermy. It could have been composed of fatty tissue and used to keep Acrocanthosaurus going for extended periods without eating. It may have also been a form of visual display for other Acrocanthosaurs to gauge its level of health, perhaps even having a different colour or markings to the rest of its body.

It is possible that the hump served double duty. If composed of fatty tissue, Acrocanthosaurus would have had to eat more than the minimum it would have had to just to survive. This would then result in a large and well maintained hump that would speak along the lines of ‘Look at my hump. That is how much of a successful predator I am. That’s why I am more worthy of passing my genes down to the next generation’. It could have also worked in dominance displays between two Acrocanthosaurus, with the larger hump meaning that they were a more capable hunter and knew what to do when things came to a fight. The Acrocanthosaurus with the smaller hump would then probably back down instead of go up against what appeared to be a stronger and more capable Acrocanthosaurus.

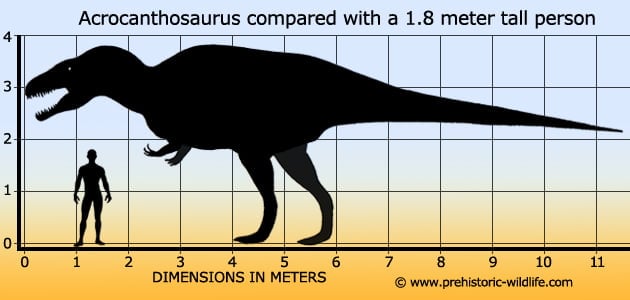

Acrocanthosaurus was big for its time, a family trait that is shared with some other carcharodontosaurids such as Carcharodontosaurus and Giganotosaurus. At eleven and a half meters, Acrocanthosaurus would have been the largest predator of its time and locale. Its diet as a result probably consisted of hadrosaurs and smaller sauropods, dinosaurs that were large enough to provide sufficient sustenance, while being too slow to escape. Study of the area that the main Acrocanthosaurus remains come from suggest that it was probably the apex predator of its location, with most other predators such as Deinonychus being much smaller.

The skull of Acrocanthosaurus featured large fenestra, a necessary adaptation to reduce the weight of its huge skull that could approach up to a one hundred and thirty centimeters long. The teeth of Acrocanthosaurus were curved and serrated like other members of the carcharodontosaurid group. The maxilla and premaxilla contained a total of around thirty-eight teeth. The teeth in the lower jaw are generally smaller than those above and can approach up to thirty in number. Another carcharodontosaurid trait is the bony brow ridge above the eye, formed by the lacrimal and postorbital bones coming together.

Computer reconstruction of the inner ear has shown that the ‘resting position’ of the head of Acrocanthosaurus was twenty-five degrees below zero horizontal. This may give the impression that Acrocanthosaurus usually walked around looking slightly towards the ground.

Reconstruction of an Acrocanthosaurus forelimb suggests that there would have been large amounts of cartilage between the bones. This comes from the fact that bones themselves do not make perfect joints and would need the extra cartilage in order to articulate properly. The arms of Acrocanthosaurus did not have a huge range of motions. The arm could not fully extend and could only manage limited flexing. The humerus could retract back quite away, as if Acrocanthosaurus was pulling something towards its chest. As is commonly seen in larger theropods, the fore arm could not twist like a human arm can. When at rest the arms would have faced medially inwards, like when you clap your hands together. Acrocanthosaurus had three digits on the end of its arms with the first and second claws probably being permanently flexed. The third and smallest claw may have been able to retract as well.

Altogether, Acrocanthosaurus may have grabbed large prey such as sauropods like Sauroposeidon with its jaws and then latched onto it with its claws. The neck vertebrae also interlocked together for greater rigidity which means that Acrocanthosaurus could hold onto large prey with its jaws without sustaining injury to the neck. Lighter prey such as ornithopod dinosaurs like Tenontosaurus may have been pulled towards Acrocanthosaurus while it continued to work with its jaws, whereas it would probably have to pull itself onto heavier prey. Alternatively it may have held its prey with its jaws while repeatedly slashing at it with its claws, the more the prey struggled, the worse its wounds became.

Further Reading

– Acrocanthosaurus atokensis, a new genus and species of Lower Cretaceous Theropoda from Oklahoma. – American Midland Naturalist 43(4):686-728. – J. W. Stovall & W. Langston Jr. – 1950. – A reanalysis of Acrocanthosaurus atokensis, its phylogenetic status, and paleobiological implications, based on a new specimen from Texas. – New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 13: 1–75.. – Jerald D. Harris – 1998. – Estimating Mass Properties of Dinosaurs Using Laser Imaging and 3D Computer Modelling. – PLoS One. 2009; 4(2): e4532. – Karl T. Bates, Phillip L. Manning, David Hodgetts & William I. Sellers, (Ronald Beckett, ed.) – 2009. – A new specimen of Acrocanthosaurus atokensis (Theropoda, Dinosauria) from the Lower Cretaceous Antlers Formation (Lower Cretaceous, Aptian) of Oklahoma, USA. – Geodiversitas 22(2):207-246. – P. J. Currie & K. Carpenter – 2000. – Acrocanthosaurus and the maker of Comanchean large-theropod footprints. – James O. Farlow – 2001. – Range of motion in the forelimb of the theropod dinosaur Acrocanthosaurus atokensis, and implications for predatory behaviour. – Journal of Zoology. 266 (3): 307–318. – Phil Senter & James H. Robins – 2005. – Cranial endocast of the Cretaceous theropod dinosaur Acrocanthosaurus atokensis. – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 25 (4): 859–864. – Jonathan Franzosa & Timothy Rowe – 2005. – New Information on the Cranial Anatomy of Acrocanthosaurus atokensis and Its Implications for the Phylogeny of Allosauroidea (Dinosauria: Theropoda). – PLoS ONE. 6 (3): e17932. – Drew R. Eddy & Julia A. Clarke, (Andrew Farke, ed.) – 2011. – Paleobiology and geographic range of the large-bodied Cretaceous theropod dinosaur Acrocanthosaurus atokensis. – Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 333–334: 13–23. – Michael D. D’Emic, Keegan M. Melstrom & Drew R. Eddy – 2012.