In Depth

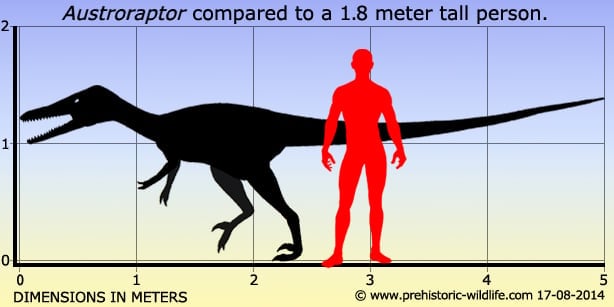

Although not as large as the North American Utahraptor, Austroraptor is still the largest dromaeosaurid currently known from South America. However to mark Austroraptor down for just this reason would be doing the genus a grave injustice as Austroraptor displays many features that make it unique among the other members of its group. First are the proportionately small forearms, limbs that are usually well developed in other dromaeosaurids so that they can get a better hold on prey as they use their sickle claws to make a kill. The skull of Austroraptor is also quite narrow and elongated which indicates a lack of developed biting muscles that in turn means a proportionately weaker bite force. Finally the teeth are not laterally compressed or serrated like other dromaeosaurids but conical and suited more for holding prey.

It’s plausible that Austroraptor may have been a niche predator that focused upon just one type of prey. The underdeveloped arms meant that Austroraptor probably did not leap onto the sides of large prey, and as such it possibly hunted smaller animals. The describers of the genus also compared the conical teeth as being similar to those of spinosaurids, a group of specialised theropods widely thought to be fish eaters. Include the weaker bite force into this mix and you have a predator that is better adapted to small prey despite its larger size.

It’s also possible that Austroraptor may have been more of a scavenger, using its size to drive off smaller predators from their kills while using its speed to avoid larger ones, but this does not support the presence of specialised teeth. Conical teeth like these are suited for holding small and possibly slippery prey like fish, not tearing flesh from a carcass. Also just as spinosaurids used the large claws on their hands to tear apart fish, Austroraptor may have used its sickle claws in a similar fashion. Although the sickle claws are more associated with stabbing rather than slashing, they may well have still been able to pull apart smaller animals so that the conical teeth and weaker jaw muscles were not a hindrance.

If the above is correct then hunting behaviour for Austroraptor may involve it using its speed to chase down small animals and using its claws to stab into their backs. Austroraptor may have also used its claws to strike out at fish in shallow water where it could then pick them out with its specialised teeth holding them firm in its mouth. On shore it could then use its claws to pull the fish into bite sized chunks for easier eating.

Further Reading

– A bizarre Cretaceous theropod dinosaur from Patagonia and the evolution of Gondwanan dromaeosaurids. – Proceedings of the Royal Society B Biological Sciences 276: 1101–1007. – F. E. Novas, D. Pol, J.I. Canale, J.D. Porfiri & J.O. Calvo – 2009. – A new specimen of Austroraptor cabazai, Pol, Canale, Porfiri and Calvo, 2008 (Dinosauria, Theropoda, Unenlagiidae) from the latest Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) of R�o Negro, Argentina. – Ameghiniana 49(4):662-667. – P. J. Currie & A. Paulina Carabajal – 2012.