In Depth

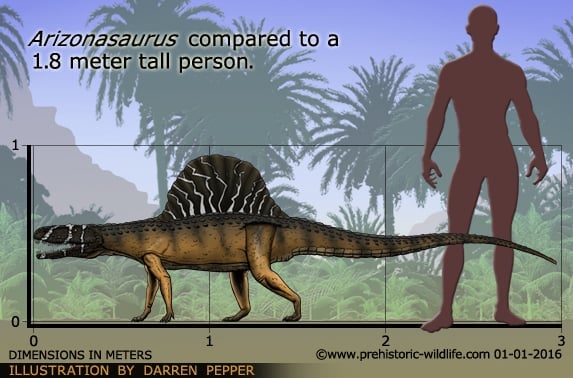

Arizonasaurus has enjoyed a lot of popularity since the discovery of a far more complete specimen in 2002. Before this Arizonasaurus was only known from very partial remains that were only diagnostic enough to classify it as a rauisuchian, reptiles that were the dominant predators of the Triassic while the early dinosaurs were still tiny by comparison. The 2002 discovery (made by Sterling Nesbitt) revealed the presence of tall neural spines across the dorsal (back) vertebrae that would have supported either a sail or hump on its back. This growth makes Arizonasaurus stand out from the other rauisuchians that as a group tend not to have any such specialised features as a back sail or hump, although the presence of Lotosaurus in Asia as well as other ctenosauriscids from across the world indicates that Arizonasaurus was not unique.

The purpose of the growth on the back of Arizonasaurus currently has an unknown function, but other prehistoric animals had these growths and the theories associated with these animals can be applied to Arizonasaurus. For example in the pelycosaur Edaphosaurus the sail seems to have been for the purpose of thermoregulation as there are a number of small horizontal spines that project from the sides that would have increased air turbulence. In Dimetrodon the sail lacked these growths, and while it may still have served the same function, it might have been more for display. In the dinosaurs Spinosaurus and Ouranosaurus similar growths may have had the same above functions, but they might also have been humps instead of sails that served as fat storage. Additionally a well-developed hump for the purpose of fat storage can also have a secondary display function as a well maintained hump means the individual it belonged to was a more successful predator, and hence more worthy of passing its genes down to the next generation.

Further Reading

– Vertebrates from the Upper Moenkopi Formation of northern Arizona – University of California Publications in Geological Sciences 27(7):241-294 – S. P. Welles – 1947. – The taxonomic status of Arizonasaurus, Welles, 1948 from the Holbrook Member of the Moenkopi Formation (Middle Triassic: early Anisian) of northeastern Arizona. In S. G. Lucas, M. Morales (eds.) – The Nonmarine Triassic. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 3:G51-G53 – A. P. Hunt – 1993. – Arizonasaurus and its implications for archosaur divergence. – Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B (supplement, Biology Letters) 270:S234-S237 – S. J. Nesbitt – 2003. – Osteology of the Middle Triassic pseudosuchian archosaur Arizonasaurus babbitti. – Historical Biology 17:19-47 – S. J. Nesbitt – 2005. – The braincase of Arizonasaurus babbitti-further evidence for the non-monophyly of ‘rauisuchian’ archosaurs. – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 26 (1): 79–87. – D. J. Gower & S. J. Nesbitt – 2006.