In Depth

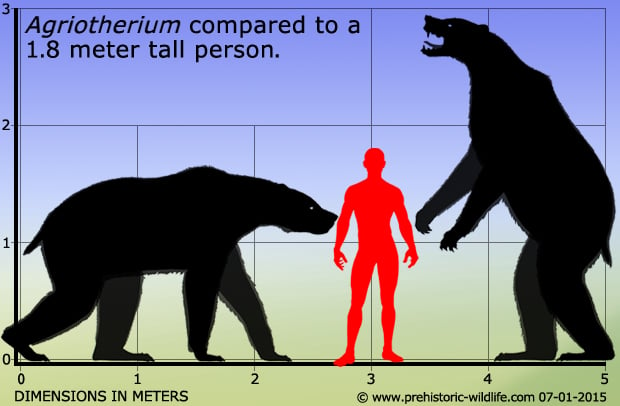

One of the better known bears in the worlds fossil record, the Agriotherium genus is also easily one of the largest currently known. With this large size it would be tempting to portray Agriotherium as a savage killers of any animal that might be unfortunate enough to be in its way, yet like with its more famous relative Arctodus (better known as the giant short faced bear) first impressions may in this case be deceptive. The post cranial skeleton of Agriotherium is that of a large but relatively underpowered animal that simply does not seem to have the skeletal framework necessary to cope with high stresses, such as those expected to be encountered while undergoing extreme physical exertion (i.e. catching and subduing struggling prey). The second clue is that Agriotherium has a proportionately short snout to that seen in many other bears. The advantages of having a short snout are simple, it means that whatever is being bitten, is closer to the point of jaw articulation (fulcrum) so that greater force can be brought to bear (no pun intended) against it.

These are all features that are common to Arctodus which also has isotopic analysis of its bones revealing that it was eating nearly every type of animal in its ecosystem, something very unusual for a predator, but common for a scavenger. Given the superficial similarity in form between Agriotherium and Arctodus, it’s reasonable to speculate that Agriotherium may have been a specialised scavenger, a theory that is becoming increasingly put forward for Arctodus. Again, the concept is very simple, by being bigger than any other predator on the land, Agriotherium could in effect bully the smaller predators away from their kills. This draws parallels in bear/wolf interaction that is observed in the wild even today, where grizzly bears will watch a pack of wolves bring down a prey animal, just to charge on in and drive them off after they have done all of the work for it. This fits with the surprisingly gracile skeleton of a large animal like Agriotherium, since if it was letting other predators do the work and the killing for it, why waste precious nutrients and calories upon developing and maintaining a skeleton stronger than it needed to be?

Another thing to consider is that if Agriotherium was a scavenger then it was likely getting to carcasses after all of the choice pieces of meat had been consumed with perhaps only bones being left. This would probably not be enough to thwart Agriotherium from a meal however since the short snout, strong jaw closing muscles and robust construction of the skull and jaws were all the things that Agriotherium needed to develop massive bite force. Computer modelling in a 2012 study (see links below) confirmed that Agriotherium had one of the largest bite forces known amongst the members of the Carnivora (A group of mammals that includes dogs, bears, cats, pinnipeds etc which are specially adapted to exist by eating meat). By being able to crack open bones, Agriotherium could access and eat the bone marrow within, and for those not familiar, bone marrow is one of the most nutritious parts of an animal, and can last for several years after an animals death when encased inside of the bones.

The idea of Agriotherium being what is termed a ‘hyper-carnivore’ is plausible, though it is not certain that Agriotherium only ate meat. Like with bears today, Agriotherium may have also supplemented its diet with fruits and certain plants, particularly tougher ones that required strong jaws. However the scavenger theory does actually fit better with Agriotherium in terms of the age of known fossils. Agriotherium first appears just after halfway through the Miocene before disappearing at the end of the Pliocene. The similar Arctodus however begins to appear in the Pliocene before becoming most numerous during the Pleistocene. It might be that Agriotherium was one of the first specialised scavenger bears but was eventually replaced in the worlds ecosystems by more advanced versions that form separate genera, as well as possibly other bone crunching animals such as hyena.

Further Reading

– Ecomorphology of the giant short-faced bears Agriotherium and Arctodus, B. Sorkin - 2006. – Finite element analysis of ursid cranial mechanics and the prediction of feeding behaviour in the extinct giant Agriotherium africanum, C. C. Oldfield, C. R. McHenry, P. D. Clausen, U. Chamoli, W. C. H. Parr, D. D. Stynder, S. Wroe - 2012. —————————————————————————-