A new study is making waves in paleontology, suggesting life on land bounced back much faster than previously thought after the end-Permian extinction.

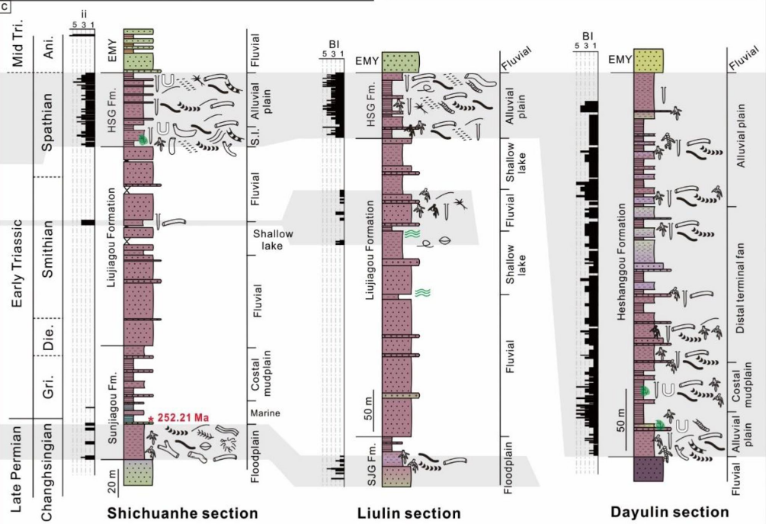

This extinction, which happened around 252 million years ago, wiped out a huge chunk of life on Earth.

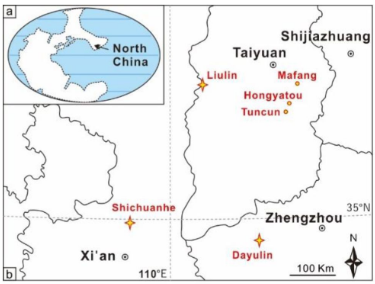

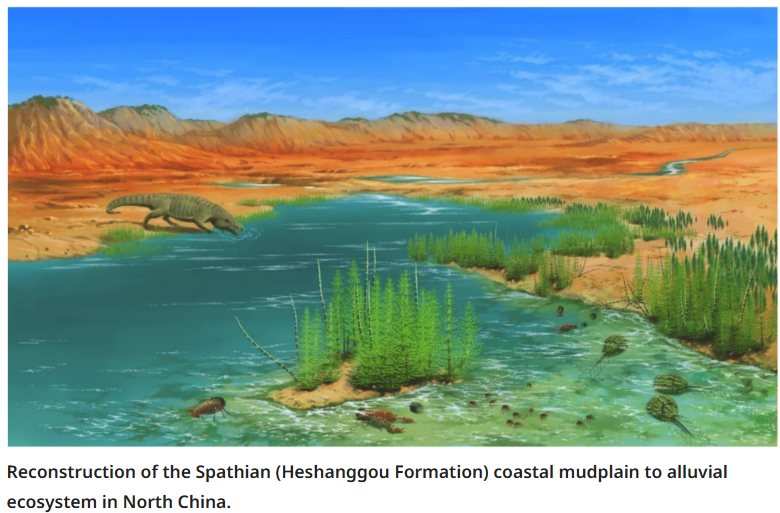

The big question has always been: How quickly did ecosystems recover? New fossil discoveries in North China are providing some surprising answers.

Riparian ecosystems, those found along rivers and wetlands, appear to have recovered in a geological blink of an eye.

Dr. Li Tian, from the China University of Geosciences, explains that while marine life recovery has been studied a lot, the story on land is less clear. This new research changes that.

The team dug into sedimentary rocks from the Early Triassic period, which followed the extinction. They looked at trace fossils (like burrows and footprints), plant remains, and vertebrate fossils.

At the start of the Early Triassic, life was tough. Fossils show only simple communities with one type of organism dominating.

Organisms were also smaller than before the extinction, a sign of environmental stress.

But, around 249 million years ago, things started to change.

The scientists found more plant stems, root traces, and burrowing activity. They even discovered fossils of meat-eating vertebrates, showing that food webs were rebuilding.

The return of burrowing animals was a key find. Burrowing helps aerate the soil and cycle nutrients, suggesting animals were adapting to survive.

These findings suggest that land ecosystems recovered much faster than expected, challenging the idea that they lagged behind marine life.

Senior author Jinnan Tong notes that rivers and wetlands might have acted as safe havens, allowing life to recover more quickly than in drier areas.

The team used various techniques, including studying trace fossils, sediments, and the chemistry of the rocks. They also looked at the sizes and depths of burrows to understand animal behavior.

The study highlights the importance of riparian zones in stabilizing ecosystems after mass extinctions. It also suggests that life is more adaptable than we might think.

More research is needed to see if similar recoveries happened in other regions. Understanding how life recovered in the past can teach valuable lessons about dealing with modern climate change.

This research, published in eLife, provides convincing evidence for a rapid recovery in tropical riparian ecosystems after a short phase of hostile environments.