Do you know about the largest prehistoric snakes, or the extinct snakes that had LEGS? Even if you know these facts, you might not have heard about the extinct snake whose discovery site’s name translates to ‘Haas’s snake from the Holy Land’. Still not surprised?

Do you know about the major debate over whether prehistoric snakes first evolved as ocean swimmers, or if they originated from land animals that began burrowing underground? One of these below extinct snake solves this mystery with its ears ,right.

I was always curious about Who were the ancestors of today’s modern snakes? I even read about this Giant ‘Ancient snake’ who was an apex predator of its time. cool right ,Top of the Food chain with no predators!

These extinct snakes were wild ,weird ,and were evolving – one fossil was discovered near sauropod eggs, and some survived even after the K-T extinction, while dinosaurs could not. Discover many more amazing features and answers to all your questions about prehistoric snakes right here!

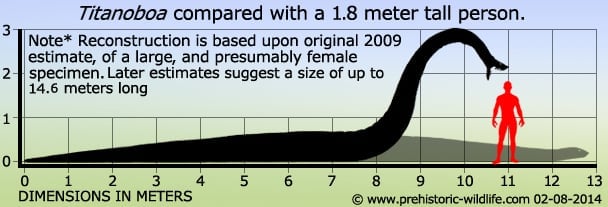

Titanoboa

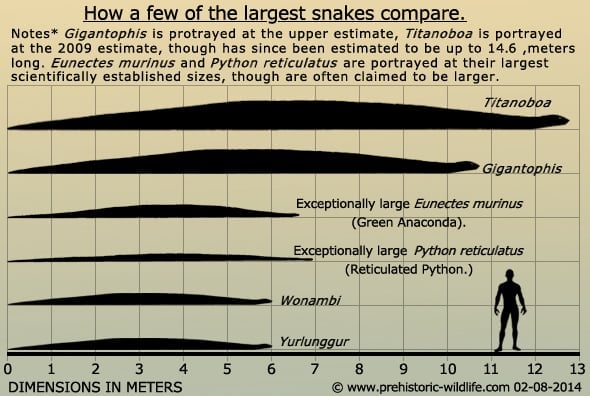

SIZE 12.8 meters? That’s over twice as long as the biggest anaconda! And wait, the Smithsonian model says 14.6 meters? So these extinct snakes were TITANIC-BOA, as the name says .

Why so Big? These Giant reptiles grow larger in warmer climates because their metabolism stays efficient . Makes sense – cold-blooded animals rely on external heat. But if Titanoboa needed such high temperatures, you can imagine the temperature it had at the Paleocene equator.

Green anacondas are the heaviest, reticulated pythons the longest. But Titanoboa dwarfs both ,amazing right !. This is common in snakes that females are larger than males and If Titanoboa followed this pattern, females might have been the true giants. But still, it’s not clear we can just imagine .

Cerrejón where this giant snake lived was a rainforest with rivers – perfect for an aquatic ambush predator. But today it’s a coal mine? Coal forms from ancient swamps, so Titanoboa’s habitat literally became fuel. Poetic.

Let’s Talk about Titanoboa diet which was “Constricting crocodiles ,Wild! Modern anacondas do it too, but Titanoboa’s prey would be massive. How did it avoid injury ?

Recurved teeth anchored prey-like fishhooks! If it latched onto a crocodile , the teeth would dig deeper if the prey struggled. Brutal. But these extinct snakes were also swallowing giant turtles , Their shells seem impossible. Unless it ate juveniles.

At the end Titanoboa vanished while smaller snakes survived because of the cooling climates or habitat shifts. Both make sense. If Cerrejón’s wetlands dried up, Titanoboa would lose its hunting grounds. But could it adapt? Maybe not….sad!

Gigantophis

Gigantophis was the ‘biggest snake ever’ for over 100 years… until Titanoboa was found in 2009.

Even though Titanoboa is longer (13–15 meters), Gigantophis ,this prehistoric snakes were still huge—over 9 meters! That’s way bigger than today’s biggest snakes (like the 7-meter python)

Gigantophis was a constrictor, like anacondas. It squeezed prey to death instead of using venom.

Imagine it attacking early ‘elephant ancestors’ (small, tapir-sized mammals). But how? Maybe ambushing them near water, just like modern snakes do.

Fossils of this extinct Snakes were first found in Egypt (Africa). But in 2014, scientists found more in Pakistan (Asia)! This means Gigantophis might have lived across Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. It probably loved warm, swampy places ,similar to Titanoboa’s habitat.

Gigantophis belongs to an ancient snake family (Madtsoiids) that lasted millions of years. Some relatives even lived in Australia!

Gigantophis died out by the late Eocene (~34 million years ago). Maybe the world got cooler, making it harder for giant cold-blooded snakes to survive. Or maybe mammals got smarter/faster, outcompeting them. We don’t know for sure.

Madtsoia

Madtsoia is the OG of the Madtsoiidae extinct snakes family? So it’s like the grandparent to Gigantophis and Wonambi.

But we don’t know how big it really was as we only have vertebrae fossils of this prehistoric snakes. But those bones still hint it was big ,though not Titanoboa-level.

Makes sense. Older snakes might’ve been smaller but still scary!

Their is a Constrictor debate on its way of hunting ,Does it do constrictor to Crush ribs or to stop the heart. But we that Modern pythons kill by suffocation .

Before KT These extinct snakes used to eat small dinosaurs or young mammals but Madtsoia adapted post-asteroid to hunt mammals, birds , or even crocodiles because crocodiles also survived after the KT using the smart ways .

Main reason for the survival of Madtsoia even when dinosaurs died was Cold-Blooded Advantage ,Lower metabolism meant they needed less food than dinosaurs.

This let them “wait out” the post-asteroid food scarcity and Even large dinosaurs with insulating feathers (gigantothermy) starved due to higher energy needs so even crocodiles outlasted them. Madtsoia’s survival post-asteroid is wild.

Snakes outlasting dinosaurs by being low-maintenance. But their success was short-lived? Since Madtsoiidae died out later. Maybe venomous snakes or mammals took over? Evolution’s brutal.

But they could eat small dinosaurs ,I mean How ?

Wonambi

Wonambi ,These extinct snakes was 5–6 meters long—bigger than a giraffe’s height.

It hunted small to medium animals (like wallabies or young kangaroos) near watering holes. Aboriginal people knew this and warned kids: ‘Stay away from the waterholes!’ Smart advice.

Wonambi lurked there, waiting for thirsty prey. Hunting style of these prehistoric snakes was Constrictor and as you have read about this from the top of the lists , you must know the meaning of constrictor Hunting – Squeezing and then swallowing the prey.

Wonambi used to Swallowed prey head-first, using sharp, backward-curved teeth to grip it (like a fishhook). Imagine it slowly sliding a kangaroo down its throat—like a modern anaconda.

Despite being deadly, Wonambi had a small skull and couldn’t unhinge its jaw like modern snakes. This meant it couldn’t eat huge animals.

Wonambi’s relatives include Yurlunggur (another Aussie giant, nicknamed ‘rainbow serpent’ in Aboriginal myths) .This snake family ruled for millions of years… until they didn’t and Another Relatives are Madtsoia (older, dinosaur-era snake, possibly bigger).

Sanajeh

These extinct Snakes were 3.5-meter-long that lived in India during the Late Cretaceous (~70 million years ago).

Fossils of this prehistoric snakes were found right next to sauropod eggs and a baby dinosaur hatchling—like catching a thief red-handed!

This sneaky snake was likely raiding nests for easy meals, helpless baby dinosaurs were the size of small dogs would be perfect meal.

Its Hunting Strategy were Nest Raiding Sanajeh targeted newborn sauropods (titanosaurs) still in their nests. Unlike modern pythons, its jaws couldn’t stretch wide.

Baby dinosaurs were the perfect bite-sized snacks for these extinct snakes! and also Sauropods grew fast-within months so, they’d be too big for Sanajeh to handle after being born.

While titanosaur hatchlings were likely its main meal, Sanajeh might’ve also eaten Theropods Like Rajasaurus (a smaller cousin of T. rex) and Small Critters like Lizards or early mammals (though no proof yet).It wasn’t picky – anything it could swallow was fair game!

Sanajeh’s family (Madtsoiidae) included Wonambi ,Australia’s waterhole ambusher. This group survived for millions of years, adapting to hunt dinosaurs, mammals, and more and Menarana , A burrowing snake from Madagascar, discovered in 2010.

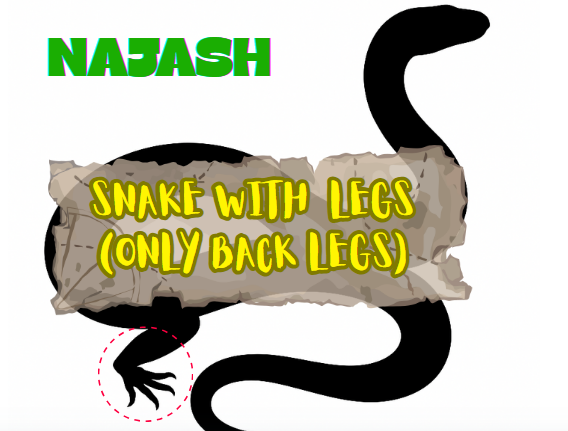

Najash

Najash were extinct snake with LEGS that lived in Argentina ~100 million years ago (Late Cretaceous).

Fossil of these extinct snakes shows how early snakes evolved from lizards.

Najash used to hung out in ancient deserts, slithering between dunes and rivers.

Najash had a jugal bone (like lizards), which modern snakes lost. This bone framed its eye socket, a clue that snakes started as modified lizards.

Unlike modern snakes, These prehistoric snakes lacked a crista circumfenestralis—a bony ear feature that helps with hearing. This means early snakes had worse hearing than today’s snakes and ears were more similar to Lizards.

Its jaws couldn’t unhinge widely like pythons. Instead, it had sharp, backward-curved teeth to grip prey – think of it like a fishhook mouth.

Najash and other legged snakes (like marine Pachyrhachis) were early branches of snake evolution not just a transition phase.

Legs stuck around for 70+ million years .It kept small back legs and hip bones, but no forelimbs—meaning snakes lost front legs before back legs.

This means Modern snakes (like vipers and pythons) evolved from a legged ancestor after Najash’s time.

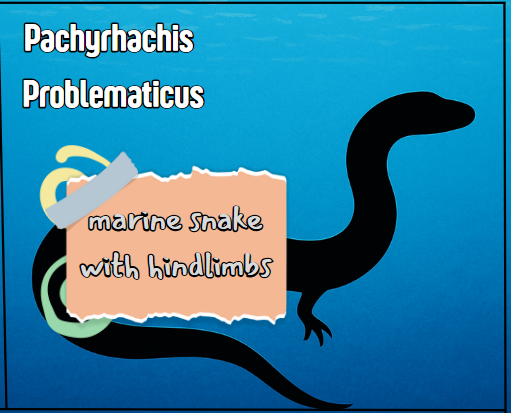

Pachyrhachis problematicus

Pachyrhachis problematicus ,These extinct snakes were marine snake with hindlimbs .

It had Long body, small head, narrow neck – streamlined for aquatic life and 145 presacral vertebrae… shows extreme elongation.

Hindlimbs were present on these prehistoric snakes but reduced as it has unfused pelvic elements and tiny leg bones.

It had No forelimbs – legg loss started from anteriorly(From the front) Possibly, reflecting early-stage limb reduction. and shows these were non functional for walking .

These extinct snakes evolved body elongation and skull flexibility before losing their legs completely.

Pachyrhachis had Thickened ribs and vertebrae (pachyostosis) – possibly to help it sink and hunt near the seafloor.

Do you think it was Slow swimmer? Likely, as given heavy bones and inferred ecology.

Gut contents which were found in this fossil were of pycnodont fish teeth (this was primarily bony fish of that time now its extinct). So this shows it was Active piscivore and it could even intake large prey at once like modern snakes.

Pachyrhachis had Flexible jaws for swallowing large prey (snake feature) ,Still had some lizard skull bones (e.g., jugal bone). This evidently shows these extinct snakes has mix of snake like and lizard like traits.

It is also believed that snakes evolved from marine reptiles (like mosasaurs), not burrowing lizards.

Dinilysia patagonica

You know how scientists are always trying to piece together how life evolved? Well, there’s this fascinating extinct snake called Dinilysia patagonica that’s been a huge help in figuring out where modern snakes came from.

In Argentina, about 90 million years ago during the time of dinosaurs. That’s where they found fossils of this prehistoric snakes.

It was about six feet long! Like snakes today, it didn’t have legs, but its skull still had some older features hinting at its lizard past.

Now, the big question about extinct snakes has always been: did they start out as swimmers in the ocean, maybe related to those giant marine reptiles? Or did they evolve from land animals that took to burrowing underground?

Dinilysia is right in the middle of this debate, and it really tips the scales towards the burrowing idea.

The really neat clue came from its inner ear. Using detailed 3D scans researchers found a part of the inner ear was big and round – a shape that’s perfect for sensing vibrations through the ground.

Think of modern snakes or even some lizards that live underground; they have similar setups to feel for prey or predators moving nearby.

What this extinct snake’s ear didn’t have were the special structures you’d expect in an animal that spent its time swimming.

So, the evidence strongly suggests this snake was a land-dweller, probably spending a lot of time burrowing or moving close to the ground.

This is pretty important because Dinilysia is thought to be closely related to the ancestor of all snakes living today.

It tells us that adapting to life underground, including developing that sensitivity to vibrations, was likely a super early step in snake evolution – maybe even happening before they completely lost their limbs (though Dinilysia itself was already legless).

It kind of throws a idea that snakes started out as sea creatures. Instead, it paints a picture of early snakes evolving in dark, hidden, underground environments.

It’s also pretty wild that Dinilysia was so big for a burrower! Lots of modern snakes that burrow full-time are quite small.

But this extinct snake shows us that the early ancestors weren’t necessarily tiny things.

So yeah, this “terrible burrower” (that’s roughly what its name means!) is a key fossil.

It’s like a bridge connecting lizards to snakes, showing us how they developed some of their signature senses to thrive in a whole new world beneath our feet.

Palaeophis

A colossal giant ruling the warm coastal waters millions of years ago. Amazing right ! That was Palaeophis, whose name literally means “ancient snake.”

These extinct snakes weren’t land snakes dipping their tails in the water; they were true sea serpents, pioneers of marine life long after the dinosaurs checked out.

These prehistoric snakes thrived during the Eocene epoch, around 56 to 34 million years ago around coastline where there was warm, shallow seas like modern-day England, Morocco, Egypt, and even parts of the eastern USA.

Now for the mind-blowing part – the size! While some Palaeophis species were just ‘large,’ others were absolute monsters.

The king, Palaeophis colossaeus found in Africa, might have stretched an unbelievable 30, maybe even pushing 40 feet (12.19 meter ) long based on its massive vertebrae! That’s longer You can imagine , making it one of the largest snakes ever to have lived.

We mostly know Palaeophis from its fossilized vertebrae, the bones making up its spine were often incredibly thick and dense – a condition called pachyostosis which was a nature’s scuba gear!

These heavy bones acted like a built-in weight belt, helping the snake stay submerged and control its buoyancy as it hunted in shallow waters.

Some scientists believe that it had paddle-like tail . It was an apex predator of its time. Its menu likely included large fish, sharks, maybe even unwary marine mammals like early sea cows or turtles.

Because skulls are almost never found, we can only guess what its head looked like or exactly how it caught its prey. It remains a fascinating Question.

Haasiophis terrasanctus

Haasiophis terrasanctus, These extinct snakes that really makes you rethink what a snake looks like! Its name is based on the name of paleontologist Georg Haas and its discovery location, meaning “Haas’s snake from the Holy Land.”

Haasiophis had legs! Not just vague bumps, but tiny, yet distinct hind limbs. These exitinct snakes had pair of small legs sticking out near its tail, complete with little ankle and foot bones.

It sounds bizarre, but it’s a fossil fact! It didn’t have front legs, though, just the back ones.

These Prehistoic snakes swam in the ancient Tethys Sea roughly 95 million years ago, during the Cretaceous period – while dinosaurs still ruled the land!

Its fossils were unearthed in limestone quarries near Ramallah in the West Bank, rocks that were once sediment on the bottom of that shallow, warm sea.

Despite its evolutionary fame, Haasiophis wasn’t a giant. It was a relatively small snake, probably less than three feet (around 80 cm) long.

It likely hunted small fish and other little critters.

Scientists think these extinct snakes were well-adapted to aquatic life, partly because some of its bones show signs of being denser than usual (pachyostosis), which would have helped control buoyancy, similar to Palaeophis but on a much smaller scale.

Haasiophis is rock-solid evidence that snakes didn’t just appear legless out of nowhere.

They evolved from four-legged ancestors (likely lizards), and Haasiophis, along with a few other similar fossil snakes (Pachyrhachis, Eupodophis), captures the transition, showing snakes experimenting with marine life while still retaining those ancestral hind limbs.

Thank you for Reading