A lot has been said about C. megalodon, and a lot of it not always true. So here are some condensed facts about this mighty shark that was once the terror of the oceans.

A quick note before we begin, this article will reference C. megalodon in the correct and standard way with reference to the ‘C.’ denoting the genus and ‘megalodon’ the species name, as opposed to just naming it ‘Megalodon’ as most other articles do.

Binomial names such as this always have two parts so that it is easier to distinguish two separate animals, even when they have either the same genus or species name, that is why it is important to write both, even if the genus name is abbreviated to just the first letter.

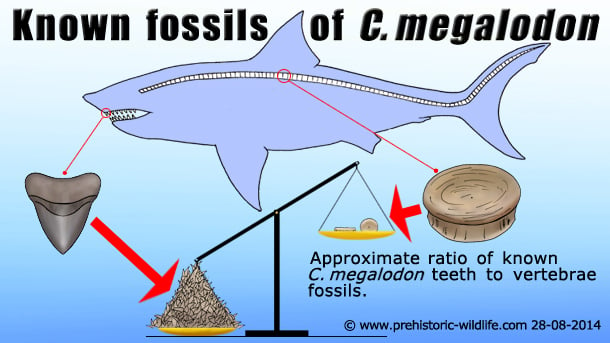

01. C. megalodon is only known from teeth and vertebrae

There have literally been tens of thousands of C. megalodon teeth discovered, ranging from partial crowns to almost complete sets.

So numerous are C. megalodon teeth, that more are discovered every day and no one can put a precise figure upon how many exist, and is why C. megalodon teeth are popular items for fossil collectors, even if they are still substantially more expensive to buy than other fossil shark teeth.

What is not so well known is that there are actually some vertebrae of C. megalodon that are also known, and in rare examples near complete spinal columns have been discovered.

Unfortunately we do not yet have any other clues as to the appearance of C. megalodon, mainly because shark skeletons are cartilaginous and decompose quickly.

Vertebrae are sometimes preserved because the cartilage here usually has a higher degree of ossification (closer to actual bone), while teeth, the hardest parts that are covered with hard enamel are the most likely parts to survive long enough to be fossilised.

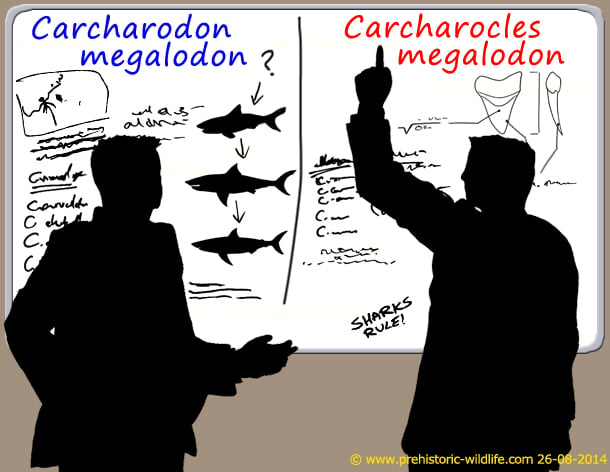

02. The Debate

The debate about the correct genus classification for C. megalodon has been going on for almost two hundred years.

In 1843 the noted Swiss naturalist Louis Agassiz formerly described the teeth of C. megalodon as belonging to the Carcharodon genus, establishing the full name of this shark as Carcharodon megalodon.

This was based upon a superficial resemblance between the teeth of C. megalodon and the teeth of Carcharodon carcharias, much better known as the Great White Shark, the largest known hyper-carnivorous shark alive today (larger sharks such as the basking and whale sharks are filter feeders).

Because of this original classification, C. megalodon has been dubbed as not only a close cousin to the great white shark, but even the probable ancestor too it.

Not everyone was convinced however, and especially in modern times less and less people are becoming convinced about this old classification.

The first problem with the notion that C. megalodon was the ancestor to the great white shark is that both C. megalodon and the great white are known to have co-existed in the world’s oceans for many millions of years.

This does not completely discount the idea of the great white being descended from C. megalodon, but it led to an alternate theory that C. megalodon and the great white may have had a common ancestor.

This was still not enough for many though. While the teeth of C. megalodon and the great white are both large and triangular, there are still several differences in form and curvature, and these are so great they are taken as some as clear signs that C. megalodon does not belong within the Carcharodon genus.

This led to the proposal that C. megalodon should be moved into the Carcharocles genus, something that at times has led to fierce debate from those who insist that C. megalodon should remain within the Carcharodon genus.

However new analytical techniques combined with new shark discoveries such as Carcharodon hubbelli suggest that the great white shark is actually descended from mako sharks, and with no known link between megatoothed sharks like C. megalodon and mako sharks, this may well indicate that C. megalodon really does belong within the Carcharocles genus.

03. C. megalodon were The largest sharks known to ever exist?

There is little doubt to the validity of this statement, C. megalodon fossils incorporate some of the largest fossil teeth of any known shark, and the vertebrae too indicate a physically large size for the body.

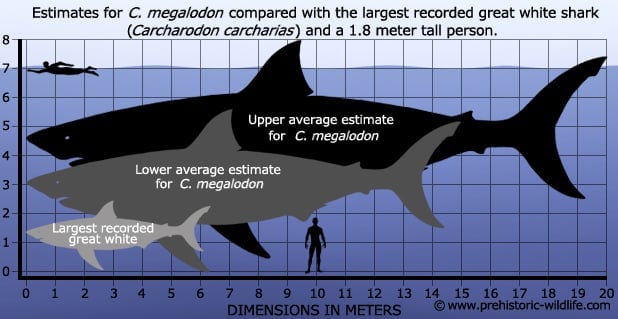

There is no definitive known size however as size estimates depend mostly upon the teeth. Some scientists measure certain lengths and ratios of the crown and compare them to other shark teeth to establish a correlation between tooth size and body size, but there are several different mathematical formulae for doing this, and often they yield different results, even when applied to the same specimen.

Other times complete jaws have been assembled from complete sets of teeth, and the remainder of the body scaled to the width of the gape.

In short the methods of establishing the size for C. megalodon are many and varied, but most palaeoichthyologists (like palaeontologists but specialising in fossils of fish) agree that a total size of around fifteen meters long is certainly attainable for the largest C. megalodon specimens.

Even larger estimates from some researchers however suggest that C. megalodon may have grown even bigger with the largest individuals approaching anywhere within the region of seventeen to even twenty meters long.

Still, even at the smaller fifteen metres mark, C. megalodon is still much bigger than any other known shark, whether alive today or in the fossil record.

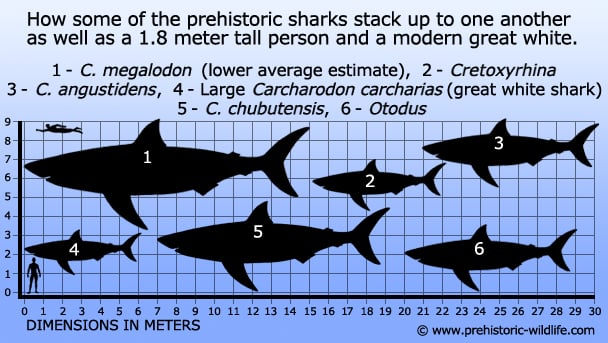

04. But C. megalodon were not the only giant sharks

C. megalodon were big, no doubt about it, but there were other monster sharks swimming in the prehistoric oceans. Other megatoothed sharks such as C. angustidens and C. chubutensis were almost as big as C. megalodon, and still much bigger than the largest recorded great white shark. Also before even C. megalodon appeared, members of the shark genus Otodus were cruising the oceanic depths.

Earlier than this back in the Cretaceous sharks such as Cretoxyrhina had also already exceeded the largest known modern day examples of the great white shark. What this proves is that even though C. megalodon was the biggest, the sharks have a very real capacity for growing to large sizes.

05. C. megalodon teeth were once thought to be dragon tongues

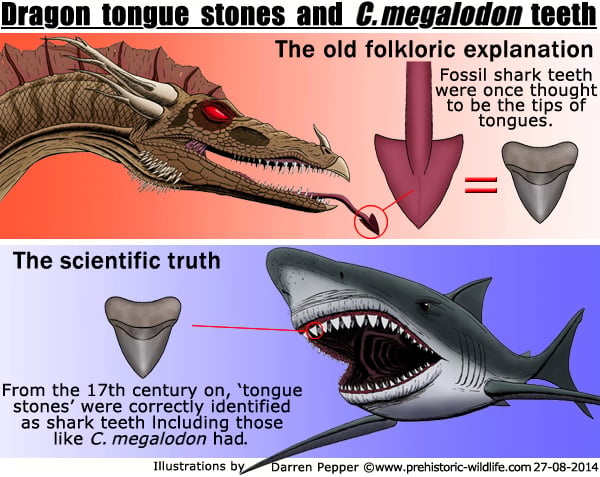

It’s true, many hundreds of years ago large fossilised shark teeth like those belonging to C. megalodon were thought to be the petrified tongues of dragons (and alternatively large snakes, large examples of which were often seen as ‘serpent dragons’).

The idea was that a dragon lost the tip of its tongue either through shedding, combat or just death, and that after it left the body the flesh had become petrified.

The word petrified is actually a combination of the Ancient Greek words for ‘stone’ and ‘turned’, and it’s possible for organic matter such as the wood of trees to become petrified and turned to stone.

So, the idea that dragon flesh had become petrified was actually a fairly intelligent interpretation of how these ‘tongue stones’ or alternatively ‘glossopetrae’ had formed, albeit they were wrong about the dragons. Because of their believed connection, these stones were believed to protect against and cure the effects of snake bites and poison.

This interpretation was a common belief until the 17th century.

The first attempt to classify these fossils as shark teeth came in 1616 in De glossopetris dissertatio by Fabio Colonna, but it was not until 1667 when Nicolaus Steno, a Danish naturalist published his work The Head of a Shark Dissected that the truth about these fossils became more widely accepted.

The knowledge that these tongue stones were really sharks teeth quickly disseminated throughout the scientific and educational bodies across Europe, and eventually this filtered to other areas of society.

06. C. megalodon were whale killers

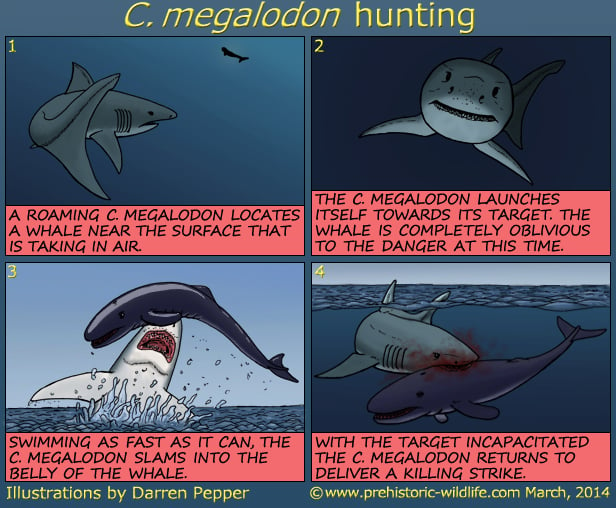

Nine times out of ten, a big predator needs big prey, and the only animals that were both large and numerous enough to satisfy the appetite of C. megalodon were whales.

This is not just blind supposition however, whales were at their most diverse and numerous during the Miocene era, and many whale fossils have been found with marks on them that could only have been caused by the tips of large shark teeth, like those that C. megalodon had.

More interesting than these however are whale vertebrae which have partial damage upon the bottom that shows these vertebrae were impacted together as if hit from below by a large predator.

It’s possible that C. megalodon may have struck smaller whales from below in a similar manner to how a great white shark will strike a seal from below today.

With the prey stunned, a C. megalodon would have time to turn around and finish the prey with a powerful bite.

Larger whales that were themselves too large for such a tactic may have still been attacked by C. megalodon, but in these instances the shark would attack the tail fluke and fins, immobilising the whale so that it could not swim away, thus allowing the shark to eat at its own leisure.

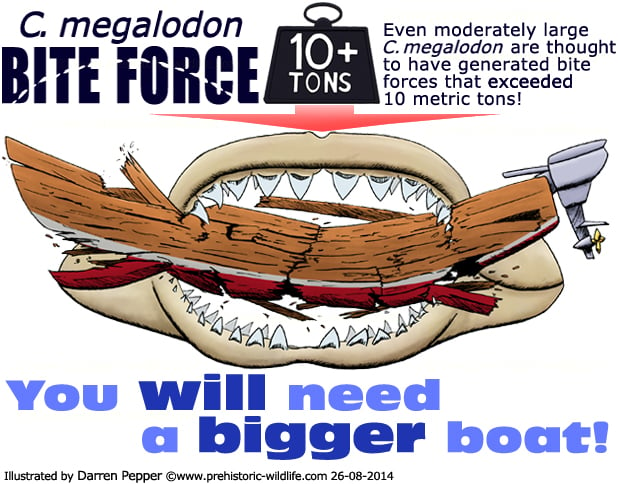

07. Large C. megalodon probably had the strongest bite of any known living creature

As a big predator C. megalodon would have had a big mouth, and comparison to other sharks indicates that the jaw closing muscles of C. megalodon would have been colossal.

One noted study (S. Wroe et al, 2008) established a range of about 108,000 - 182,000 newtons (11 - 18.5 metric tons) posterior bite force (bites are strongest nearer to the point of jaw articulation due to force focusing) for lower and upper maximum size estimates of C. megalodon.

This study was based around the jaw mechanics of the great white shark, which in turn led to the largest known example of a great white shark having a bite force of 18, 216 newtons (1.85 metric tons).

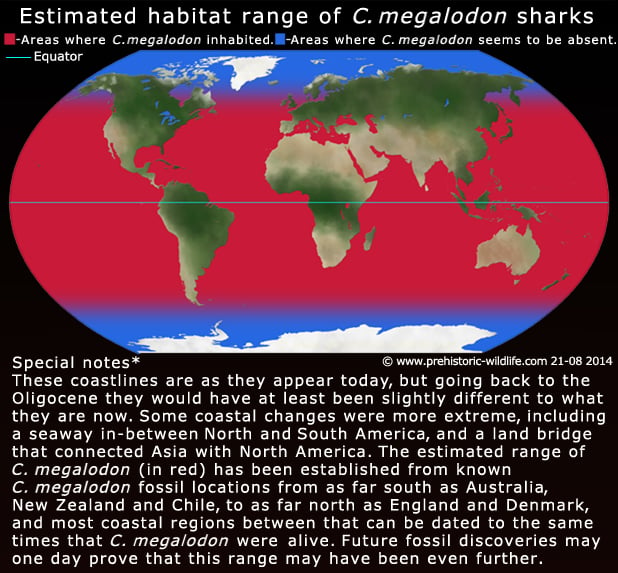

08. C. megalodon lived in oceanic waters across the globe

C. megalodon is known to have had what is termed a cosmopolitan distribution because fossil teeth of this shark have been discovered in age appropriate coastal/marine rock deposits all over the world.

The only exception to this idea is that so far C. megalodon teeth have not been found around waters of the extreme north and extreme south, waters that would have been much cooler than those near the equator.

This has led to the suggestion that C. megalodon may have had metabolisms that operated faster than typically ‘cold-blooded animals, and had to stay in warmer and more temperate waters where they would not have needed such a large calorie intake to maintain this metabolism.

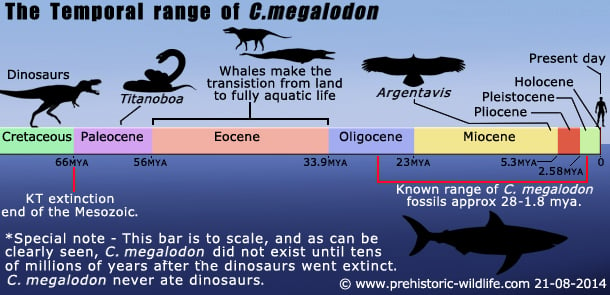

09. The most recent known fossils of C. megalodon are roughly 1.8 million years old

C. megalodon had a very broad temporal range with fossil teeth going all the way back to the late Oligocene, and not disappearing from the fossil record until the late Gelasian period of the Pleistocene some 1.8 million years ago.

However there was once a rare exception to this with a fossil C. megalodon tooth (one of at least two) that was first discovered in 1872 during a voyage by HMS Challenger.

When tested in 1959 this tooth was credited as being only 10,000 years old, making it supposed proof that C. megalodon only went extinct in recent times.

However, the 10,000 years date was worked out by measuring the level of manganese dioxide build up upon the fossil specimen, and today we now know this to be a highly unreliable method of testing age because the level of manganese dioxide on two fossils of the same age and can vary wildly.

When the tooth was re-tested with radio carbon dating, a clear result could not be achieved, but this in itself would indicate that the tooth was much older than 10,000 years.

For the record, at the time of writing even the most advanced and experimental radio carbon dating techniques can only give a date if a specimen is less than a few hundred thousand years old. When fossils are established as being many millions of years old, it is usually from establishing the age of the rocks that they have come from.

10. C. megalodon is now one of the most popular prehistoric animals to feature in popular fiction

Whenever people first hear the name C. megalodon, usually just as ‘Megalodon’ it’s usually within the context of an appearance in a film, novel or other work of fiction, and that’s no real surprise.

Although C. megalodon was first named in 1843, for the first hundred and fifty years it received surprisingly little attention, and when it did it, it was usually just as ‘giant shark’. From the 1990‘s onward however, and coinciding with the rise in internet access and use for the first time, C. megalodon quickly began to occupy the public’s imagination.

With a public demand for more information (and much easier and cheaper access to computer special effects), C. megalodon has been featured in everything from written fiction such as novels to low budget films and Discovery Channel ‘documentaries’ (stop laughing!).

Part of this interest can actually be traced back to 1975 with the cinematic release of Jaws, though this was actually just one of many ‘killer shark’ movies from the 1970s.

Since this time stories featuring abnormally large and aggressive sharks going on a rampage have become standard B. movie fodder, and worldwide there are now literally hundreds of such films. With C. megalodon credited as being the largest shark, it is both monstrous yet familiar enough for people to recognise.

Unfortunately beyond the name and large size, most writers and producers don’t care to be factually correct about C. megalodon.

Across various works of fiction C. megalodon is often portrayed as much bigger than it actually was, something that used to hunt and kill dinosaurs, something that ‘was’ a dinosaur, capable of leaping thousands of feet out of the water, having the power to sink even big warships, lying dormant and frozen in icebergs and still living in the deepest darkest depths of the ocean.

Because these works of fiction have often been the first and even only introduction that people have had to C. megalodon, they are often taken as ‘truths’ and passed around as such.

Films and books that are intended as stories for entertainment are no real problem, when written well they can be very entertaining even with scientific inaccuracies.

What is disturbing though is the development of the ‘fake-umentory’, a television show presented as a factual documentary yet is actually composed of faked footage with actors portraying the scientific ‘experts’ and ‘witnesses’ for the purpose of ‘entertainment’, and although brief disclaimers about the shows are aired during broadcast, these are often very short and more often misunderstood by the viewers.

Most infamous was the Discovery Channels Megalodon: The Monster Shark Lives, though with this feature fast becoming one of the Discovery Channel’s more popular shows (thanks largely to its infamy), and a follow up ‘documentary’ a year later, it is easy to understand the great temptation of more unscrupulous television producers to substitute fact for fiction. Remember, as with all things, never rely upon only one source for your information.

Do you want even more information on C. megalodon? Visit the main C. megalodon page that has even more in depth information about this shark.