In Depth

The modern history of the sauropod dinosaur Barosaurus begins in 1889 with the discovery of the first Barosaurus fossils by a Ms E. R. Ellerman in South Dakota. Six caudal (tail) vertebrae were subsequently recovered by the famous American palaeontologist Othniel Charles Marsh later that year, though other remains were left at the site until such time that they could be safely recovered and transported. In 1898 one of Marsh’s assistants, George Weiland recovered these remains which included limbs, ribs and more vertebrae, and allowed for the identification of Barosaurus as a diplodocid sauropod. Later, fossils of Barosaurus were the last to ever be described by Charles Othniel Marsh before his death in 1899. These were two metatarsals assigned to a new species, B. affinis, though today this species is treated as a synonym to the type species, B. lentus.

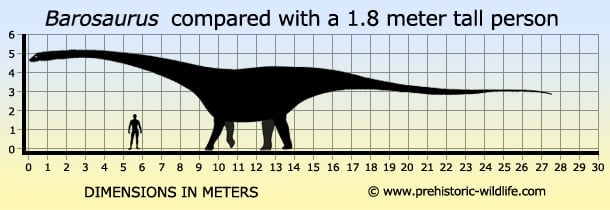

Today Barosaurus is known by the remains of several individuals that have all been recovered from the Kimmeridgian aged deposits of the famous Morrison Formation. As already mentioned, Barosaurus is a diplodocid sauropod, which means that it was of the kind that were very long with slender necks and tails that were whip-like on the end. It should be mentioned at this point that the end of the tail of Barosaurus is still unknown at the time of writing, but it would be highly unusual for a diplodocid to not have a whip-like tail. Barosaurus can be further classified as a diplodocine diplodocid rather than an apatosaurine diplodosaurid. Diplodocines are classed under the Diplodocinae and they are different to the apatosaurines (classed under the Apatosaurinae) in that they are more gracile (lightly built) than their heavier cousins.

The main features that make Barosaurus unique to other diplodocids are in the vertebrae, and usually Barosaurus is compared to the famous Diplodocus and Apatosaurus . Both Diplodocus and Apatosaurus have fifteen cervical (neck) and ten dorsal (back) vertebrae. Barosaurus is known to have had fifteen cervical vertebrae but only nine dorsal vertebrae. Where the tenth dorsal vertebra went to is unknown, but it’s possible that it may have over time adapted to become a sixteenth cervical vertebrae. The cervical vertebrae of Barosaurus were also up to one and a half times longer than the cervical vertebrae of Diplodocus meaning that Barosaurus would have proportionately longer neck than Diplodocus. The caudal (tail) vertebrae of Barosaurus however were proportionately shorter than those of Diplodocus, meaning that the overall length of the tail would have been shorter in Barosaurus. The neural spines of the vertebrae in Barosaurus are also shorter and less complex than those of Diplodocus.

Much of the post cranial skeleton of Barosaurus is known, though there are two glaring omissions; the feet and the head. Barosaurus is actually not an exception, the feet and skulls are the two most commonly missing parts when sauropod remains are found. This is because they are fairly small and jointed and therefore can become easily detached from the rest of the skeleton before preservation. As a diplodocid, Barosaurus would be expected to have had a skull similar to relative genera, elongated with a sloping snout, housing peg-like teeth for stripping vegetation from branches.

Aside from being similar to Diplodocus and Apatosaurus, Barosaurus also seems to have shared the same habitats as them as well. Another sauropod named Haplocanthosaurus may have also come into contact with Barosaurus. In addition to these, macronarian sauropods such as Camarasaurus and Brachiosaurus would have also been present on the same landscapes as Barosaurus. There would have course been other dinosaurs such as herbivores like Stegosaurus, Camptosaurus and Mymoorapelta, and predators such as Ornitholestes, Torvosaurus, Saurophaganax and Allosaurus. Barosaurus may have fallen prey to some of these larger predators, though the smaller juveniles would have been at more of a risk than fully grown adults.

For a time Barosaurus was once thought to have lived in Africa as well as North America. This all comes down to a 1907 discovery of two sauropod skeletons by a German palaeontologist named Eberhard Fraas, who at the time thought that he was creating a new genus of sauropod named Gigantosaurus. However, the name Gigantosaurus had already been named for a more obscure set of sauropod remains from England, so a new genus was erected for them by Richard Sternfeld and named Tornieria in 1911. Fossils of Tornieria africana however were re-assigned by another German palaeontologist named Werner Janensch to Barosaurus. Since this however, other palaeontologists have questioned the reasoning of such a move. One species formerly known as T. robustus was re-examined in 1991 and revealed to be a titanosaurs and added to its own new genus Janenschia. Other material once assigned as T. africanus was confirmed to be different to known North American diplodocids in 2006, which saw a subsequent resurrection of the Tornieria genus. This also rather obviously means that Barosaurus remains known only from North American deposits. ROM 3670

One of the most exciting discoveries, or rather rediscoveries concerning Barosaurus happened in 2007. Palaeontologist and curator of the Royal Ontario Museum David Evans spotted a reference to a Barosaurus skeleton that had been traded with the Carnegie Museum and sent to the Royal Ontario Museum in 1962. Strangely, these fossils don’t seem to have made it out of storage upon arriving and just disappeared from everyone’s memory. Realising that there might be a scientifically valuable specimen somewhere in the museum, Evans searched the storage bays and began finding the fossils of the missing Barosaurus.

This Barosaurus specimen is known as ROM 3670, though those who visit and work with it know it better as ‘Gordo’. With the rediscovery plans were immediately put into motion to set up a new display, though in order to get the display ready, not all of the fossil casts could be mounted in time. In fact more bones of Barosaurus were still in storage several years after this mounting was completed which means that it may be re-mounted but more completely in the future. Unfortunately the skull is still not known, so the one that appears upon the display is that of a Diplodocus, which should at the very least be a fairly close match.

ROM 3670 is valuable for two reasons. With more fossils of this dinosaur coming out of storage, it may actually be the most complete Barosaurus skeleton so far recovered. This skeleton also seems to have come from an individual which seems to have grown up to twenty-seven and a half meters long, making it the largest individual Barosaurus known.

Further Reading

- Description of new dinosaurian reptiles - Othniel Charles Marsh - 1890. - The sauropod dinosaur Barosaurus Marsh: redescription of the type specimens in the Peabody Museum, Yale University - Richard S, Lull - 1919. - Sauropod dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic), Black Hills, South Dakota and Wyoming - John R. Foster - 1996. - A phylogenetic analysis of Diplodocoidea (Saurischia: Sauropoda) J. A. Whitlock - 2011. – The neck of Barosaurus was not only longer but also wider than those of Diplodocus and other diplodocines. – PeerJ Preprints. 1: e67v1. – Michael P. taylor & Mathew J. Wedel – 2013.