In Depth

Named after the title character in the 1942 film Bambi, Bambiraptor was a small dromaeosaurid dinosaur that has caused a lot of excitement in the science of palaeontology. Discovered by a fourteen year-old Wes Linster in 1993, the Bambiraptor holotype is of an exceptionally well preserved individual that is estimated to be around a ninety-five per cent complete dinosaur. In addition to this the bones display very little distortion (fossils often become distorted due to the immense pressures of layers of rock lying on top of them, especially in lightly built animals) so it has been relatively easy for palaeontologists to reconstruct this dinosaur when compared to what they usually have to work with. This has led to Bambiraptor being popularly dubbed a ‘Rosetta stone’ after the discovery of the stone that allowed for the decryption of Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs, but in Bambiraptor the reference is more to it revealing answers about the dromaeosaur dinosaurs.

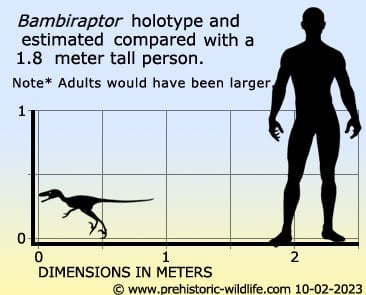

The holotype fossil for which Bambiraptor is named is of a juvenile dinosaur, something that has led to some controversy over the facts and actual validity of this genus. Firstly is that Bambiraptor is often credited at being ninety centimetres long, but because the most complete specimen is only that of a juvenile, it is a certainty that adult Bambiraptor would have been bigger than this. In 2010 Gregory S. Paul estimated the length of an adult Bambiraptor at a larger one hundred and thirty centimetres long, which if accurate would still make Bambiraptor small, but nearer the size of other small dromaeosaurs.

Another misconception is that of intelligence, since Bambiraptor is thought to have had a large brain in relation to the size of its body. The size of the brain in proportion to the size of the body is termed Encephalization quotient, or EQ for short and basically works upon the principal that the larger the brain is in relation to the body the more intelligent the animal. This is why dinosaurs with a high EQ level like Troodon are often credited as being the most intelligent dinosaurs, but the theory is a controversial one. The main problem here is that the method for determining EQ does not fully take into account the kind of brain tissues involved, which is why an animal with a brain double the size of another animal with a same sized body can be seen on paper to have double the intelligence, even if the extra size was only attributed to something like extra brain cells for a greater sense of smell. The animal with a smaller brain however might have a larger cognitive centre (memory, problem solving, etc.) and actually be more intelligent than the larger brained animal but with less capable senses (smell, vision, etc.). Additionally you have to remember that the Bambiraptor holotype is of a juvenile, and juvenile creatures usually do have proportionately larger brains than adults because even though their bodies are still growing, they still need to be smart enough to process their surroundings. As such determining EQ especially from a juvenile can give a skewed interpretation of an animal’s actual intelligence.

Another thing that needs to be considered is that animals, and particularly some dinosaurs have been seen to make marked morphological changes as they reach different ages (a good example being the leg proportions between juvenile and adult tyrannosaurs), and being described from a juvenile specimen, some palaeontologists have considered the possibility of Bambiraptor actually being a juvenile of a previously described genus. Here some have pointed to the similar Saurornitholestes as the possible adult form of Bambiraptor, however most other palaeontologists continue to support the idea that Bambiraptor should be treated as a distinct genus.

One thing that is likely for Bambiraptor whether it was a juvenile or adult is the presence of feathers. Although not confirmed to be present in the holotype or any other remains so far attributed to the genus, many of the other dinosaurs that Bambiraptor is related to be known to have had them. Additionally some that have not had feathers preserved do also sometimes have the attachments for even better developed feathers. If indeed present upon the body, then Bambiraptor probably would have had a covering of primitive downy feathers that served as insulation.

Because of its small size, Bambiraptor is thought to have been a hunter of small mammals and reptiles like lizards which would have been very common small prey during the Late Cretaceous. The arms of Bambiraptor are thought to have been very dexterous as well as fingers that were semi opposable. What this means is that Bambiraptor could have possibly held small prey in its arms and actually lift them up to its mouth for easier feeding. It’s also possible that this greater dexterity may have also been for climbing. Bambiraptor however would have faced competition from slightly larger related dinosaurs such as the aforementioned Troodon and Saurornitholestes as well as Dromaeosaurus. Other threats could have also been the tyrannosaurs Daspletosaurus and Gorgosaurus, particularly juveniles of these two genera which would have been a lot faster and more agile than adults.

Bambiraptor has sometimes been credited with two species names when in fact it currently only has one. The species name B. feinbergi is in honour of both Michael and Ann Feinberg who bought the holotype from a fossil dealer and then donated it to science. However because feinbergi is in the singular vernacular, a pluralised version of feinbergorum was later proposed. This was used by a few people at first, but under naming guidelines set out by the ICZN (the body that governs the naming of animals) the first species name is not only valid but still has priority over the new version. For this reason Bambiraptor feinbergorum is now treated as a synonym to Bambiraptor feinbergi.

Further Reading

– Remarkable new birdlike dinosaur (Theropoda: Maniraptora) from the Upper Cretaceous of Montana. – University of Kansas Paleontological Contributions 13: 1-14. – D. A. Burnham, K. L. Derstler, P. J. Currie, R. T. Bakker, Z. Zhou & J. H. Ostrom – 2000. – New Information on Bambiraptor feinbergi from the Late Cretaceous of Montana. – D. A. Burnham – 2004. – Comparison of forelimb function between Deinonychus and Bambiraptor (Theropoda: Dromaeosauridae). – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 26(4): 897-906. – P. Senter – 2006.