In Depth

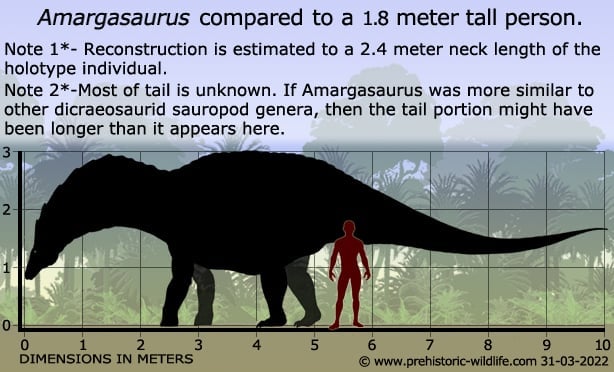

Amargasaurus has easily become one of the most popular dinosaurs thanks to the elongated neural spines of the neck vertebrae that are immediately apparent from even a casual glance at the skeleton of this dinosaur. Technically known as hemispinous processes, these spines rise up from the top of the vertebrae and are bifurcated, which means they split into two separate spines from a combined base on top of the vertebra.

Since the discovery of Amargasaurus there has been a lot of theory and speculation as to how the enlarged neural spines affected the appearance of this dinosaur. One of the first main ideas was that the spines supported a double skin sail that started just behind the head and along the neck and sometimes the body too. This sail was conceived as being mainly for display but possibly also thermoregulation. Sometimes depicted as rising all the way to the tip of the spines and at other times only part way up the main problem with the skin sail idea was that it would have resulted in a neck that was probably very rigid, and an actual encumbrance to feeding and drinking.

The second main idea that became even more popular was that there was no skin sail, the neural spines would have risen up just by themselves. Being bone the spines would have had to have a keratinous covering to protect them from exposure to the elements and physical damage. They were still possibly used for display but in this configuration possibly also as weapons to help Amargasaurus defend itself from predators. It was also considered that the spines may have rattled against one another so that they not only formed a visual display, but an audial display too. However problems with the weapon and contact ideas can be pointed out as the spines are directly connected to the neck, an area that can easily incur mortal injury if damaged. Either the spines were strong enough to be used with physical force, which increased the likelihood of damage to the vertebrae and spinal column, or the spikes were designed to break before that happened, but that weakness would make them pretty useless as weapons. However, it now seems that all of the above are moot points because as we are about to read there is now a third theory. In 2022 a scientific paper (Cerda et al) was published providing what was the most in-depth study of the cervical vertebrae that had been done up to that point. This study looked at everything from the structure to the microanatomy of the bones. One of the key things to immediately come out of this study was there was no evidence of keratinous covering for these neural spines. This was concluded not only from micro analysis of bone which was highly vascularized, but by the presence of growth marks. Even more telling was evidence for the presence of Sharpey’s fibres connecting to the spines so that a whole system of interspinous ligaments may have connected the spines. These ligaments also seem to have gone all the way to the ends of the neural spines. What this all means is that the spines of Amargasaurus probably didn’t stand proud of the body, and in all likelihood supported a soft tissue growth that rose up from the back of the neck and down towards the body.

Why Amargasaurus had such a growth to its neck can never be known with absolute certainty. There has long been debate to how sauropod dinosaurs breathed and how they got air along their necks and into their bodies. Maybe the growth above the neck of Amargasaurus helped facilitate the transfer of oxygen rich air along the neck, but if this is the case then why are these structures not commonly seen in other sauropod types and certainly not to this degree of specialisation? Perhaps the most likely function of the neck is display, allowing Amargasaurus to easily recognise others of their kind as well as attracting mates. As for the rest of the body Amargasaurus is typically classed as a dicraeosaurid sauropod, a sub group of the diplodocid sauropods. Dicraeosaurids have long thin whip like tails, but necks that are actually quite short, at least when compared to other sauropod dinosaurs. There is speculation that necks that are enlarged above the vertebral column may actually be present in other dicraeosaurid sauropods even if not to the size extent of Amargasaurus. If correct then this would lend more support to the display idea for the neck shape. It would also possible explain why dicraeosaurid have proportionately shorter necks, the extra growth upwards would add weight and bulk, making a shorter neck much easier to manage than a longer neck.

Studies done on the partial skull remains of Amargasaurus in 2014 (Carabajal et al) indicate that in life Amargasaurus probably held its head down as in the mouth pointing more towards the ground as opposed to perfectly horizontal. This snippet of information was revealed by modelling of the inner ear which revealed that if horizontal registered as 0�, and vertical was 90�, then the snout would point at the ground at about 65�. In the study re-construction of the inner ear also revealed that Amargasaurus would have had poorer hearing than many other sauropod dinosaurs.

It has also been noted in the 2014 study that the typical resting posture of the head of Amargasaurus would place it a little under 1 meter from the ground, but possibly rising as much as 2.7 metres off the ground when the neck was raised and the neural spines compressed. However that information was established before the 2022 paper redefining the spines as being supported by ligaments, and with that extra soft tissue it might mean that Amargasaurus might not have been able to raise its head off the ground as much as previously thought. A range of motion in the neck would still have been possible, but to a less certain extent. Dicraeosaurid sauropods are usually viewed as being very low browsers anyway, a feeding niche that would mean that sauropod dinosaurs like Amargasaurus could avoid competing directly with the increasing types of larger titanosaurs that were present in South America.

Other interesting sauropods with hyper developed neural spines from the Cretaceous of South America include Bajadasaurus and Agustinia.

Further Reading

– Un nuevo saur�podo Dicraeosauridae, Amargasaurus cazaui gen. et sp. nov., de la Formaci�n La Amarga, Neocomiano de la provincia del Neuqu�n, Argentina [Amargasaurus cazaui gen. et sp. nov., a new dicraeosaurid sauropod from the La Amarga Formation, Neocomian of Neuqu�n province, Argentina] – Ameghiniana 28(3-4):333-346 – L. Salgado & J. F. Bonaparte – 1991. – Cranial osteology of Amargasaurus cazaui Salgado and Bonaparte (Sauropoda, Dicraeosauridae) from the Neocomian of Patagonia – Ameghiniana 29: 337-346. – L. Salgado & J. O. Calvo – 1992. – Giants and bizarres: body size of some southern South American Cretaceous dinosaurs – Historical Biology 16 (2-4): 71–83. – G. V. Mazzetta, P. Christiansen & R. A. Farina – 2004. – The sauropod diversity of the La Amarga Formation (Barremian), Neuqu�n (Argentina) – Gondwana Research 12:533-546 – S. Apesteguia – 2007. - Braincase, neuroanatomy, and neck posture of Amargasaurus cazaui (Sauropoda, Dicraeosauridae) and its implications for understanding head posture in sauropods.- Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 34 (4): 870–882. - Ariana Paulina Carabajal, Jos� L. Carballido & Philip J. Currie - 2014. - Osteohistology of the hyperelongate hemispinous processes of Amargasaurus cazaui (Dinosauria: Sauropoda): Implications for soft tissue reconstruction and functional significance. - Journal of Anatomy: 1–15. - Ignacio A. Cerda, Fernando E. Novas, Jos� Luis Carballido & Leonardo Salgado - 2022.