In Depth

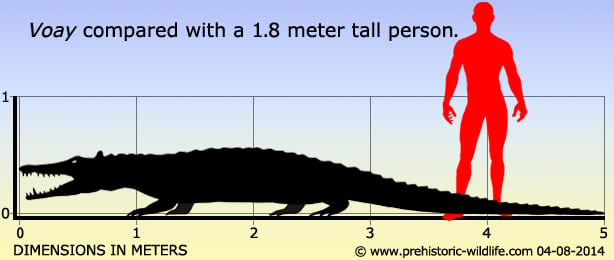

The remains of the crocodile Voay were first described as a species of Crocodylus (C. robustus) back in 1872 by Grandidier and Vaillant, however later study found that the remains were nearer to the dwarf crocodile Osteolaemus, although not close enough to be included with this genus either. For this reason C. A. Brochu created a new genus under the name Voay in 2007, and in keeping with standard practices for naming new genera and species from existing classified material, the species name of robustus was retained to create a new type species of Voay robustus.

The remains of Voay which include skulls, vertebrae and osteoderms (the bony armour plates in the skin that are also sometimes called ‘scutes’) are classed as sub fossils which mean that they have not been completely fossilised. These remains are also dated to as recently as two thousand years ago, something that suggests that the genus went extinct with the arrival of the first humans upon Madagascar. This also coincides with the disappearance of other large animals from Madagascar at this time which has led to theory that human hunting may have been a factor in the disappearance of these animals. Although Voay is dated during the Holocene, a disappearance two thousand years ago would on paper suggest that the genus only lived ten thousand years. Realistically however, Voay probably also existed into the at least the late Pleistocene era, but further fossil remains from different time periods would be needed to establish and confirm a more complete temporal range for this genus.

The Nile crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus) is also known from Madagascar, but there is some debate concerning whether the Nile crocodile and Voay co-existed in Madagascar at the same time, or if Nile crocodiles colonised Madagascar to fill a predatory void left behind by the disappearance of Voay. At this point either theory is plausible since although similarly sized, Voay is morphologically different to the C. niloticus. One key area is the more robust limbs, and since crocodiles usually rely upon their tails for swimming, the stronger limbs might suggest that Voay spent a greater amount of time on the land than C. niloticus. This could also mean a stronger disposition towards hunting and possibly even scavenging on land, which would infer different specialisation and behaviour to the C. niloticus.

Voay also has a proportionately shorter and deeper snout than C. niloticus with nasal openings that are also reduced in size. This also infers a different prey specialisation to the longer and more slender snouted C. niloticus and if the two lived in the same habitats, it’s possible that they may have been able to coexist by adopting different lifestyles. A precedent could be established by looking at South American crocodiles of the Miocene. Here you had three giant crocodiles called Purussaurus, Gryposuchus and Mourasuchus. All three lived in the same approximate geographic area but each specialised in a different feeding strategy. Purussaurus had a skull similar to a caiman, indicating that it was a hunter of large prey. Gryposuchus however was more like a gharial (alternatively gavial) and was suited to hunting fish. Finally Mourasuchus seems to have been a filter feeder that consumed large amounts of small prey animals. Even though we still don’t know exactly how well these three crocodiles got on, it is possible that they could inhabit the same water systems without competing for the same food as one another.

Voay did have a pair of horns that grew from the back of its head that were actually extensions of the squamosal bone (one of the most rearward portions of the skull). These horns are often seen in other crocodiles as well, which has led to the more common term of these species and genera being called ‘horned crocodiles’.

Further Reading

– Description of a skull of the extinct Madagascar crocodile, Crocodilus robustus Vaillant and Grandidier. – Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 44 (4): 25. – Charles C. Mook. – The giant dwarf crocodile: a reappraisal of ‘Crocodylus’ robustus from the Quaternary of Madagascar. In: Patterson, Goodman & Sedlock, eds., Environmental Change in Madagascar. p. 70. – C. A. Brochu & G. W. Storrs – 1995. – Morphology, relationships, and biogeographical significance of an extinct horned crocodile (Crocodylia, Crocodylidae) from the Quaternary of Madagascar. – Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 150:835-863. – C. A. Brochu – 2007. – The late Pleistocene horned crocodile Voay robustus (Grandidier & Vaillant, 1872) from Madagascar in the Museum f�r Naturkunde Berlin. – Fossil Record 12: 13. – C. Bicklemann, N. Klein – 2009.