In Depth

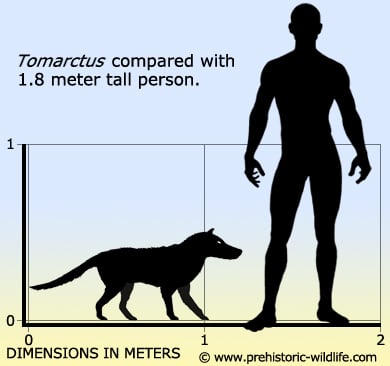

A relative of such genera as Aelurodon and Borophagus, Tomarctus is another one of the hyena-like ‘bone crushing’ dogs of the Miocene. This description comes from the attachments for powerful jaw closing muscles and short muzzle which means that when borophagine canids like Tomarctus bit on something, it was closer to the point of jaw articulation. This in turn means that the force from the muscles is focused so that it is concentrated upon a smaller area so that more damage could be done to whatever is being bitten. This is exactly the same with a modern hyena.

The high bite force of Tomarctus is beyond that necessary to kill an animal, which leads to speculation that scavenging was just as an important part of the diet as was hunting, perhaps even more so. Scavengers however usually get to a carcass after most if not all of the fleshy parts have been devoured, probably by the animal or animal that made the kill. This would be no problem for an animal with jaws like those of Tomarctus however since it had the necessary jaw adaptations for cracking open the bones so that it could get at the marrow within. Bone marrow by itself is one of the most nutritious things in the natural world, and when encased in bone under the right conditions it can last for months and even years after the death of an animal. However, just because Tomarctus was well suited to being a scavenger, it does not mean that they never killed their own prey.

Tomarctus is known to have existed for at least the first half of the Miocene, and seems to have disappeared with the appearance of later borophagine forms like Aelurodon. During the early half of the Miocene Tomarctus would have lived amongst other groups of carnivores such as false sabre-toothed cats, bear dogs and entelodonts.

Further Reading

- Small mammal fossils from the Barstow Formation, Califonia. – E. H. Lindsay - 1972. - Phylogenetic systematics of the Borophaginae. – X. Wang, R. H. Tedford & B. E. Taylor - 1999.