In Depth

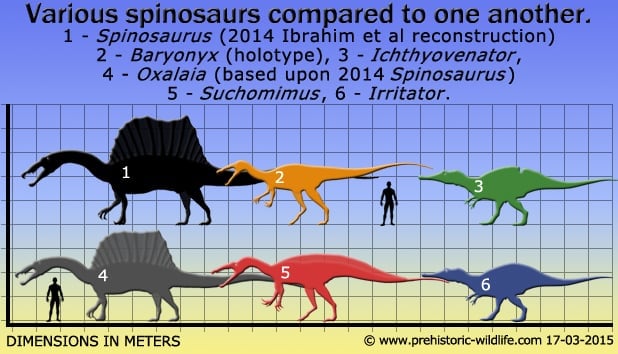

The discovery of Suchomimus helped towards the more accurate reconstruction of its potentially much larger relative Spinosaurus. Combined with knowledge from the discovery of Baryonyx and new partial skull material attributed to Spinosaurus remains resulted in Spinosaurus finally being given a crocodile-like skull instead that of the more typical theropod skull style. These discoveries combined to help establish a whole new group of theropod dinosaurs, the spinosaurids.

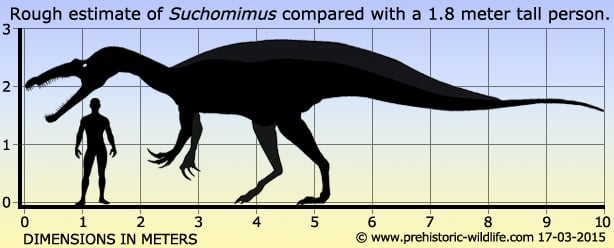

Because the spinosaurids are a newer group there is still much to learn about them, especially given the often poor nature of their fossils. Suchomimus itself seems to be somewhere between Baryonyx and Spinosaurus in that it is larger than the former and smaller than the latter, and also displays the development of tall neural spines along its dorsal vertebrae. In Spinosaurus these neural spines are even larger, a feature that gave rise to its name which translates as ‘Spine lizard’. Baryonyx however does not display any special elongation to the neural spines, the key reason why it is regarded as a separate genus.

However this reason has been called into question on the principal that the Baryonyx holotype was not a full grown individual. Suchomimus itself was not full grown but still a subadult thought to have been near its maximum adult size. This has caused many palaeontologists to contemplate the possibility that both Baryonyx and Suchomimus are actually the same genus of dinosaur and that the neural spines did not begin to grow until the individual approached adulthood. Currently it is by no means certain that the two are synonymous, but if ever discovered, fossil material for a near identical spinosaurid of a size between the sizes of the Baryonyx and Suchomimus holotypes that shows an intermediate development of the neural spines, would throw a lot of weight in support of the synonym theory.

As a living animal, Suchomimus probably lived the lifestyle that has been speculated for all other spinosaurids. This meant that it probably roamed the semi aquatic environments such as river deltas and lagoons of early Cretaceous Africa while specifically looking for fish. This fish specialisation can be clearly seen in the long snout and lower jaw that contains many long, yet comparatively thin teeth that are better suited for seizing slippery prey like fish. The premaxilla also exhibits a rounded notch that fits with the rounded growth of the lower jaw, a feature that further enhances prey capture.

Suchomimus probably did not rely exclusively upon fish for its diet and fossil evidence for spinosaurids suggests that they were opportunists that fed upon dinosaurs as well as pterosaurs. However what is not known is if they actually hunted dinosaurs or scavenged the remains of already dead animals. The fact that the teeth were adapted for catching prey rather than killing it, may suggest that Suchomimus had a greater reliance upon scavenging. It also needs to be remembered however that Suchomimus had enlarged claws on its hands, a feature so far thought to be common amongst spinosaurids due to their association with spinosaurid remains. With this in mind, Suchomimus may have been able to grip smaller ornithopod dinosaurs like Ouranosaurus with its mouth while slashing at the neck with its enlarged claws. The enlarged neural spines along the back of Suchomimus were obviously there for a purpose, with the two most common suggestions being for the support of either a skin sail or a hump. This debate currently also exists for Spinosaurus with theories ranging from thermoregulation to display to food storage (the latter more for the hump theory). The robust nature of the neural spines lends more weight to the hump theory as they seem to be unnecessarily large for supporting a skin sail. This growth may have been more similar to that of Acrocanthosaurus than Spinosaurus itself.

The overall body plan of Suchomimus may have been similar to the form of the South American spinosaurids like Irritator. South American Spinosaurids are so far mostly known from partial skulls and associated teeth and vertebrae. During the Early Cretaceous South America and Africa had split but were still much closer to one another, and fossil evidence of similar dinosaurs from both continents suggests that land bridges would have existed to allow new species to cross over, at least until the early Cretaceous.

Further Reading

– A long-snouted predatory dinosaur from Africa and the evolution of spinosaurids. – Science 282:1298-1302. – P. C. Sereno, A. L. Beck, D. B. Dutheil, B. Gado, H. C. E. Larsson, G. H. Lyon, J. D. Marcot, O. W. M. Rauhut, R. W. Sadleir, C. A. Sidor, D. D. Varricchio, G. P. Wilson & J. A. Wilson – 1998. – The furcula in Suchomimus tenerensis and Tyrannosaurus rex (Dinosauria: Theropoda: Tetanurae). – Journal of Paleontology 81 (6): 1523–1527. – Christine Lipkin, Paul C. Sereno & John R. Horner – 2007.