In Depth

Ptychodus was one of the most specialist sharks of the late Cretaceous oceans, as the teeth are adapted for crushing shells rather than tearing through flesh. As such the teeth are rounded rather than being triangular and pointed, and have a series of ridges that run across the surface of the crown. These ridges would have increased the bite pressure along the length of the ridges, something that would have helped to hold onto smooth shelled shellfish while also focusing the bite pressure onto key areas of the shell, making it easier for Ptychodus to break it. It is actually these ridges that give a folded appearance to the teeth that were the inspiration for the name of the shark which when broken down becomes a combination of ‘ptych’ which means ‘fold’ or ‘layer’, and ‘dus’ which means ‘tooth’.

When first discovered the teeth of Ptychodus were thought to have belonged to a ray, a bottom dwelling type of cartilaginous fish that are related to the sharks. Later it was thought to be hybodont, a shark similar to Hybodus that had crushing teeth at the back of its mouth but more regular pointed teeth at the back. Even later analysis combined with new fossil discoveries now suggests that Ptychodus was a neoselachian, the group of sharks that appeared during the Cretaceous which are thought to be the direct ancestors to today’s modern sharks.

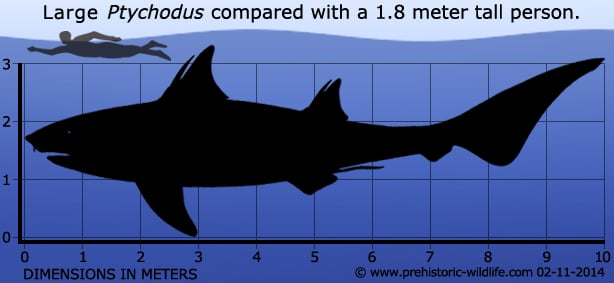

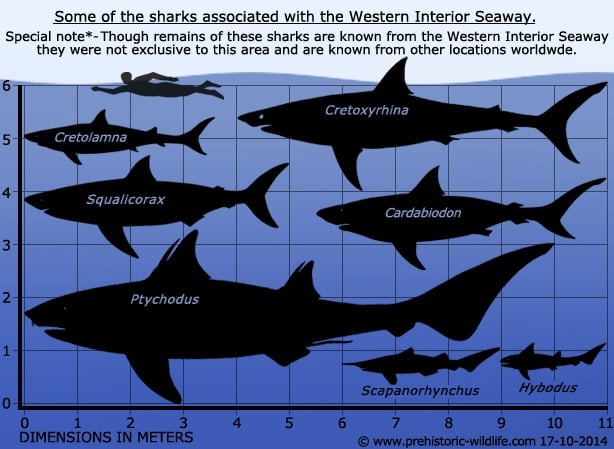

Analysis of Ptychodus fossils has indicated that it was possibly around ten meters long, something that would actually make Ptychodus one of the largest sharks of the Cretaceous, even bigger than the hyper carnivorous Cretoxyrhina that grew up to seven meters long. However Cretoxyrhina was a pelagic (open ocean) predator of other marine creatures whereas Ptychodus was probably more of a benthic (bottom) predator of shellfish and crustaceans which it could easily eat with its specialised teeth. It might seem strange that a shark could grow so large upon a diet of shellfish, but back in the Cretaceous waters there were giant inoceramid bivalves such as the almost two meter wide Inoceramus. Large prey animals like this combined with a more sedentary lifestyle compared to the pelagic sharks meant that Ptychodus could easily afford to grow large. Additionally by being a benthic creature Ptychodus may not have come into much contact with the apex predators of the Cretaceous seas, namely the mosasaurs. As marine reptiles the mosasaurs had to remain within reach of the surface so that they could breathe in air, similar in fashion to whales. Sharks do not need to do this however because they have gills that can extract oxygen from the water, which meant that if a Ptychodus was ever harassed by a mosasaur it would just have to stay down until the mosasaur couldn’t hold its breath any longer. Despite the reduction in the numbers of predators that a full grown Ptychodus faced, a small number of teeth from another shark called Squalicorax have been found in association with Ptychodus remains, something that raises the possibility that a Squalicorax fed upon a Ptychodus. This does not reveal the cause of death for the Ptychodus however, as it may not have been killed by the Squalicorax, but just scavenged by it. Nonetheless this does help piece together a part of the marine ecosystems of the Cretaceous where sharks like Ptychodus kept the numbers of large bivalves in check while other sharks ‘cleaned up’ the remains of dead animals by eating them.

Further Reading

– Recherches Sur Les Poissons Fossiles. Tome III (livr. 10, 12). – Imprim�rie de Petitpierre, Neuchatel 141-156. – L. Agassiz – 1837. – On the Teeth of Ptychodus and their Distribution in the English Chalk. – Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society, 67, 263-277. – George Edward Dibley, F.G.S. – 1911. – A Late Cretaceous durophagus shark, Ptychodus martini Williston, from Texas. – The Texas Journal of Science, vol56 issue 2 – Shawn A. Hamm & Kenshu Shimada – 2004. – Comment on “The oldest stratigraphic record of the Late Cretaceous shark Ptychodus mortoni Agassiz, from Vallecillo, Nuevo Le�n, northeastern Mexico”. – Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Geologicas, 25(2) – Blanco-Pi��n et al. – 2007. – Partial Skull of Late Cretaceous Durophagous Shark, Ptychodus occidentalis (Elasmobranchii: Ptychodontidae), from Nebraska, U.S.A. – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 29(2), pp 336-349 – Kenshu Shimada, Cyntihia K. Rigsby & Sun H. Kim – 2009. – The Late Cretaceous Shark Ptychodus marginalis in the Western Interior Seaway, USA. – Journal of Paleontology 84(3), pp 538-548 – Shawn A. Hamm – 2010. – A new skeletal remain of the durophagous shark, Ptychodus mortoni, from the Upper Cretaceous of North America: an indication of gigantic body size. – Cretaceous Research, Vol 31 Issue 2, p249-254. – Kenshui Shimada, Michael J. Everhart, Ramo Decker & Pamela D. Decker – 2010. – Dentition of Late Cretaceous shark, Ptychodus mortoni (Elasmobranchii, Ptychodontidae). – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, vol 32 issue 6 – Kenshu Shimada – 2012. – The first tooth set of Ptychodus atcoensis (Elasmobranchii: Ptychodontidae), from the Cretaceous of Venezuela. – Swiss Journal of Palaeontology, vol 132 issue 1 pp 69-75 – Jorge D. Carrillo-Brice�o & Spencer G. Lucas – 2013. – Senior synonyms of Ptychodus latissimus Agassiz, 1835 and Ptychodus mammillaris Agassiz, 1835 (Elasmobranchii) based on teeth from the Bohemian Cretaceous Basin (the Czech Republic). – Acta Musei Nationalis Pragae, Series B – Historia Naturalis, 71(1–2): 5–14 – A. Brignon – 2015. – Le diodon devenu requin : l’histoire des premi�res d�couvertes du genre Ptychodus (Chondrichthyes) [The porcupinefish that became a shark: History of the early discoveries of the genus Ptychodus (Chondrichthyes)]. – Published by the author, Bourg-la-Reine, France, 100 pp., ISBN : 978-2-9565479-2-1. – A. Brignon – 2019.