In Depth

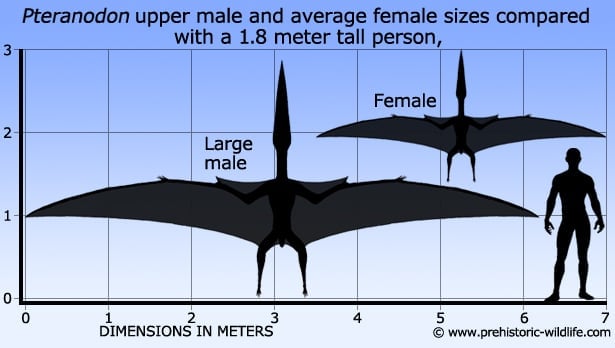

Multiple species and the differences between male and female.

Much like the pterosaurs Pterodactylus and Rhamphorhynchus, Pteranodon has suffered from the wastebasket taxon effect. This is because at the time of its discovery it was the only known toothless pterosaur, and as such any remains that suggested a toothless pterosaur were almost automatically included into the genus. As such, an ever increasing list of species names started to appear when in reality the fossils were all representative of the same species.

Pteranodon fossils display two distinct groups of small and large individuals with quite a large degree of crest variation, although again, these crests can also be broken down into individual groups. When these fossils were first discovered they were taken as being examples of different species and genus, but towards the end of the twentieth century, new studies revealed that these differences were actually evidence of sexual dimorphism.

The more complete sets of remains that were attributed to the smaller Pteranodon morph actually showed a proportionately wider pelvis that would have allowed for a much easier passage of eggs. The smaller morphs also had different shaped crests than the larger examples of Pteranodon, with the smaller members having more triangular crests. The larger Pteranodon specimens had crests that curved upwards and backwards, with some skulls showing signs of a second low crest that ran towards the tip of the beak.

Piecing all these bits together reveals that the crest in males was a sign of sexual maturity and an aid in dominance displays. The smaller crests in the smaller morphs were mostly representative of females, with the exception of the remains with a narrower pelvis which probably represented immature males that had yet to develop the head crest of adulthood. This does of course mean that establishing the difference between male and female in the smaller specimens can be difficult where the pelvis has not been preserved.

Briefly returning to the problem of multiple non-existent species, the new studies allowed for the reduction of these names to the two distinct species of P. longiceps and P. stembergi. There are still other species which are now considered to be Nomen dubium, and these include Pteranodon comptus, P. ingens, P. occidentalis, P. umbrosus, P. velox, Pterodactylus ingens, P. umbrosus and P. velox. There are also some sets of remains that remain attributed to different genera yet may yet be revealed to actually belong to Pteranodon, and as such the list of synonyms for Pteranodon is likely to change and even grow with time.Distinguishing features

The head crest is by far the most distinctive feature of Pteranodon, although many of the classic depictions of this pterosaur only seem to depict a straight and narrow crest that angles back from the back of the skull. Determining the full extent of the crest is reliant upon the age of the individual and how well it has been preserved, although there is a great degree of known variation from the standard long and straight, to the highly ornate upwards pointing crests that can be seen in remains of P. stembergi.

As for practical function, it seems almost certain that the crest was only for display as it is greatly reduced in specimens that are confirmed female, and shows signs of still developing in immature males. As a display device, it probably would not have been just a case of large size and shape, but would probably been brightly coloured to accentuate its presence to mates and potential rivals.

Practical functionality of the crest still remains an active topic with the most popular theory explaining the crest as a rudder to help steering, pretty much like in a modern aeroplane, although at the front and with a greater degree of potential movement. It is also thought by some that it may have supported a growth of skin between its head and its back, perhaps not just to increase its surface area, but also to create a form of display structure that could be erected when it pitched its head forward.

Although the crest is regarded by most to have been for display, as noted in the difference between female, male and immature male specimens, it should not be forgotten that such a structure would have invariably had an impact upon the aerodynamics of Pteranodon. It may even have had a negative impact on a males ability to hunt for fish, reducing the amount of time a male could stay in his prime, increasing the chance of genetic variation as males replaced one another, and also going some way to explain the greater abundance of female and immature male specimens over the remains of males that would be regarded as being at the peak of their masculinity.

Aside from the crest, the most prominent feature of Pteranodon is the toothless beak which at the time of discovery was unknown in pterosaurs as all other species before its discovery had teeth. This means that instead of relying upon teeth to seize its prey, Pteranodon may have used a scooping motion instead.Flight ability

Pteranodon was long considered to be just a huge glider, its size making it impossible to flap its wings making it reliant upon strong up draughts present at coastal locations. However this is now considered to be an out dated and erroneous view of Pteranodon’s flight capabilities. Studies of the wing strength compared to body weight have revealed that flapping would have certainly been possible, and indeed necessary when lifting off from the ground.

Pteranodon is often associated with the Albatross because of similarities with wing proportions, and this coupled with further studies has brought the summarisation that Pteranodon flew like large sea birds do today like the just mentioned Albatross. This means that when flying over the ocean looking for fish, Pteranodon used a method of flight that is referred to as dynamic soaring.

Dynamic soaring is where a flying creature such as an Albatross flies into the trough formed by two waves and into the lee of a passing wave. The lee is the change that results in stronger air pressure that occurs as the wave moves along, and this pressure results in air moving faster over the wings, and increasing their lift. The animal in question can then turn around sharply, a process called ‘wheeling’, and then head back towards the trough with a back wind that further increases speed. Lee waves are also formed around land objects such as mountains and are sometimes exploited by glider pilots to keep their aircraft in the air for longer.

By utilising this method of flight, Pteranodon could indeed fly for extended periods without flapping, although this would be more a case on energy conservation as opposed to inability. It also means that Pteranodon likely flew for extended periods while looking for food and maybe at range too. How migratory Pteranodon was in uncertain, although because the remains seem to be attributed to the Western interior seaway, it may have had a limited global distribution.

When not flying, Pteranodon is now thought to have been bipedal like other known pterosaurs, supporting itself by leaning forward onto its wings. This is different from many early views that had Pteranodon reared up on its hind legs with its wings well away from the ground. Although no hard evidence exists for quadrupedal locomotion in Pteranodon, it does exist for a number of other pterosaurs. Also, there is no evidence that Pteranodon was only bipedal, and until such evidence can be proven to exist, the quadrupedal method remains the most likely.Diet

As for diet, the remains of fish including the scales and bones make it certain that the diet of Pteranodon was mostly if not exclusively fish. The actual feeding strategy is still unknown and subject to debate but includes three distinct possibilities. The first and most widely accepted view is that Pteranodon flew low over the water and scooped up fish with its beak while it was still in flight. The second involves Pteranodon actually landing on the water and then snatching fish up as it bobbed around on the surface. The third makes the suggestion that Pteranodon would plunge into the water from a height and use its velocity to dive deep under water, increasing the chance of prey capture. The final theory comes from the observation that the head and shoulders of Pteranodon had a robust construction similar to today’s diving birds.Relationships

The number of remains attributed to female Pteranodon greatly outweighs the known males, and this has brought the suggestion that Pteranodon was a polygynous animal. This means that males would mate with several females as opposed to just forming a mating pair. Comparison with animals that are known to be polygynous today would suggest that dominant Pteranodon males would take up territories in prominent locations. The Pteranodon with the largest and perhaps also the most vividly coloured head crest would keep away other males that did not have such an elaborate display.

Further Reading

– The Vertebrata of the Cretaceous formations of the West – Report, U. S. Geological Survey of the Territories (Hayden), 2: 302 pp., 57 pls. – E. D. Cope – 1875. – Notice of a new sub-order of Pterosauria – American Journal of Science, Series 3 11 (65): 507–509. – O. C. Marsh – 1876a. – Principal characters of American pterodactyls – American Journal of Science, Series 3 12 (72): 479–480. – O. C. Marsh – 1876b. – The characters of Pteranodon. – American Journal of Science, ser. 4, 16(91):82-86, pl. 6-7. – G. F. Eaton – 1903. – The characters of Pteranodon (second paper). – American Journal of Science, ser. 4, 17(100):318-320, pl. 19-20. – G. F. Eaton – 1904. – Stomach stones and the food of plesiosaurs – Science 20 (501): 184–185 – B. Brown – 1904. – The skull of Pteranodon. – Science (n. s.) XXVII 254-255. – G. F. Eaton – 1908. – Osteology of Pteranodon. – Memoirs of the Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences, 2:1-38, pls. i-xxxi. – G. F. Eaton – 1910. – Ein Lebensbild von Pteranodon ingens auf flugtechnischer Grundlage. – Nova Acta Leopoldina, N.F., 12(83): 16-32 – D. von Kripp – 1943. – Pteranodon sternbergi, a new fossil pterodactyl from the Niobrara Cretaceous of Kansas. – Proceedings South Dakota Academy of Science 45:74-77. – J. C. Harksen – 1966. – The taxonomy of the Pteranodon species from Kansas – Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions 74(1):1-19. – H. W. Miller – 1971. – A skull of Pteranodon (Longicepia) longiceps Marsh associated with wing and body parts. – Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions 74(10):20-33. – H. W. Miller – 1971. – Biomechanics of Pteranodon. – Philosophical Transactions Royal Society B, 267 – C. D. Bramwell & G. R. Whitfield – 1974. – Dynamic analysis of Pteranodon ingens: a reptilian adaptation to flight – Journal of Paleontology 49: 534–548. – R. S. Stein – 1975. – A functional analysis of flying and walking in pterosaurs – Paleobiology 9 (3): 218–239. – K. Padian – 1983. – The aerodynamics of Pteranodon and Nyctosaurus, two large pterosaurs from the Upper Cretaceous of Kansas. – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 3(2):84-124. – J. C. Brower – 1983. – Sexual dimorphism of Pteranodon and other pterosaurs, with comments on cranial crests – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 12 (4): 422–434 – S. C. Bennet – 1992. – Taxonomy and systematics of the Late Cretaceous pterosaur Pteranodon (Pterosauria, Pterodactyloida) – Occasional Papers of the Natural History Museum, University of Kansas 169: 1–70. – S. C. Bennet – 1994. – The Pterosaurs of the Niobrara Chalk. – The Earth Scientist, 11(1): 22-25. – S. C. Bennet – 1994. – An early occurrence of Pteranodon sternbergi from the Smoky Hill Member (Late Cretaceous) of the Niobrara Chalk in western Kansas – Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions 18(Abstracts):27. – M. J. Everhart – 1999. – Inferring stratigraphic position of fossil vertebrates from the Niobrara Chalk of western Kansas. – Current Research in Earth Sciences: Kansas Geological Survey Bulletin, 244(Part 1): 26 pp. – S. C. Bennet – 2000. – The osteology and functional morphology of the Late Cretaceous pterosaur Pteranodon. General description of osteology – Palaeontographica, Abteilung A 260: 1–112 – S. C. Bennet – 2001. – The osteology and functional morphology of the Late Cretaceous pterosaur Pteranodon. Part II. – Functional morphology. Palaeontographica, Abteilung A, 260:113-153. – S. C. Bennet – 2001. – Pteranodont claw morphology and its implications for aquatic locomotion – Master’s Thesis, Michigan State University. – A. C. Smith – 2007. – Comments on the Pteranodontidae (Pterosauria, Pterodactyloidea) with the description of two new species. – Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ci�ncias. 82 (4): 1063–1084. – A. W. A. Kellner – 2010.